As spring arrived exactly one century ago in 1915, the world’s leading nations geared up for the second year of The Great War.

This will be the year of U-Boat campaigns, including the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania, the first use of poison gas, the increasingly effective use of airplanes and the “Fokker Scourge,” Italy’s entering the war on the side of the Allies, brutal trench warfare, and the Gallipoli campaign.

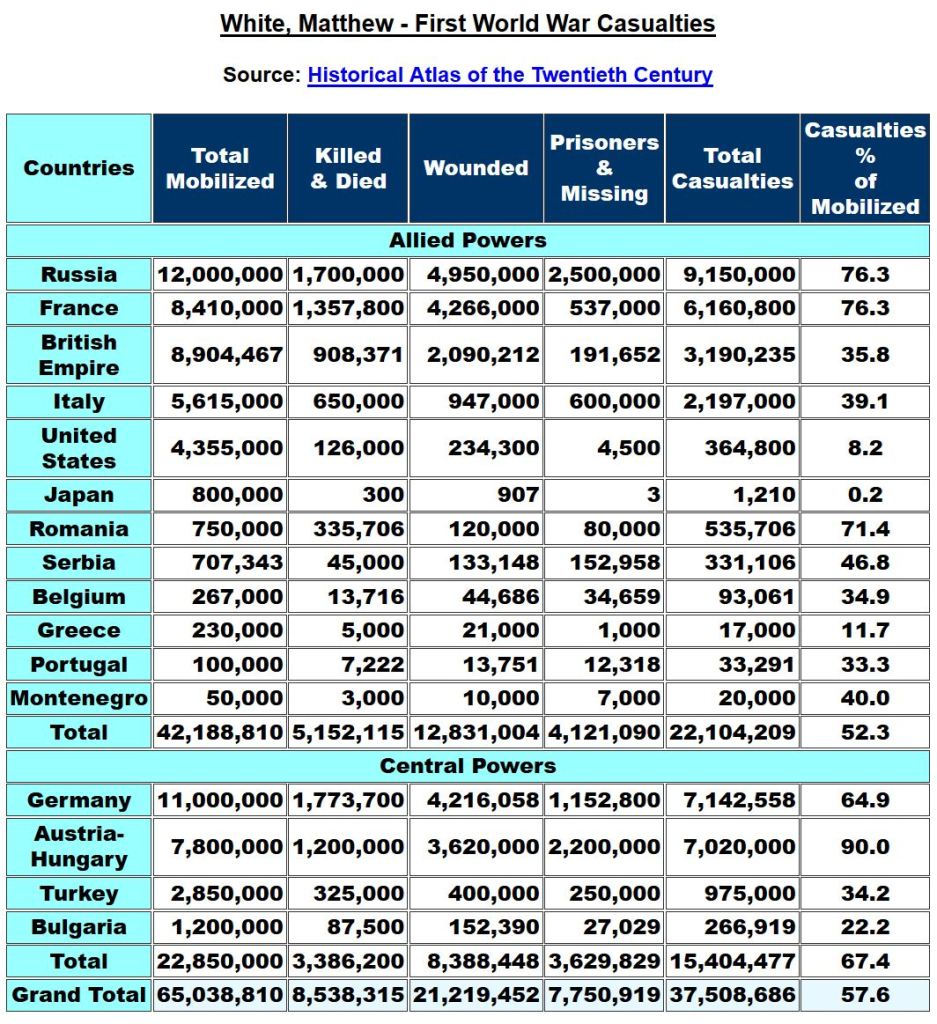

Via Richard Koenigsberg, here is Matthew White’s table summarizing a large body of data about casualties for the war as a whole:

Beyond the depressingly huge numbers, some details in the numbers raise questions in my mind:

1. Note the casualty rates for the seven countries that mobilized more than four million troops each (Russia, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and the United States). Four of them are in the 65-90% range, two of them are in the 35-40% range, and one is an outlier at 8.2%. Why? Because the USA entered the war later? Because of different fighting strategies?

2. Note the ratio of Wounded to Killed for most countries. Typically the Wounded:Killed ratio is 2:1 or 3:1. Except for Romania, whose ratio is reversed and is almost 1:3. Why?

I can’t find the reference at the moment, but I have seen several studies showing that the casualty rate among U.S. troops was the about same as the French, British, and Germans, in terms of killed/wounded per day of combat. Total U.S. losses were lower than other countries because their units were not in combat as long as other countries.

The Romanian statistics are appalling! A quick search turns up no explanation, though. The most obvious guess would be lack of medical care or medical supplies, and a correspondingly higher rate of mortal wounds.

Thanks, Neil, for the clarification.

Romania had a particular disastrous war:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romania_during_World_War_I

Losing two-thirds of your territory probably made looking after sick and wounded much more difficult, even leaving aside the scale of their military defeat.

I’m not an expert on these statistics Stephen–but sometimes differences in casualties relate to the PROMISCUITY WITH WHICH SOLDIERS ARE SENT INTO “battle.” Check out the website above, which provides information on the Italian case.

Here’s a passage from the book: “Giovanni Papin wrote with relief in Lacerba when the war began: “A warm bath of black blood” was needed, and finally the people were getting it. “It is a wholesale slaughter,” he continued gleefully.

“This frantic slaughter is good for the Italians,” Papini wrote in agreement with Marinetti, because “we Italians are too many,” because there is too much “rabble” and too many “idiots” among us, and because there is an “infinity of people who are absolutely useless and superfluous.” War and slaughter would conveniently get rid of this worthless mass.

I have a photo of Russian troops being sent into battle with no rifles.

It’s a mistake to think of this war in conventional terms–as if nations are trying to “win.” The war provided the occasion when nations could send young men to be slaughtered.

Americans (after the Civil War) are not quite so promiscuous about sacrificing young men. Think of General Patton, “The goal of war is not to die for your country, but to get the other poor bastard to die for HIS COUNTRY.”

Thanks very much for continuing to following Library of Social Science publications.

Best regards,

Richard K.

Thanks, Richard. Those cultural differences about the willingness to sacrifice oneself and others are very important, which I why I respect your work on the moral psychology of war. I recall a biography of the general MacArthur, and the author went out of his way to praise MacArthur for having the lowest death rate for the soldiers under his command. Patton also scored well by that criterion.

Good source and explanation, Lorenzo. Thanks.

And of course, Stephen, there is that statement that Patton is famous for having made: “No bastard ever won a war by dying for his country. He won it by making some other poor dumb bastard die for his country.”

The United States may be somewhat LESS sacrificial than other nations/cultures–killing the other becomes a substitute for sacrificing one’s own. Although I hypothesize that the fundamental dynamic still is sacrificial–the American soldier doesn’t kill out of anger or aggression or hatred–

but to facilitate the other’s sacrifice wish–his desire to die for his country (or religion).

I like the Patton line very much.

About the psychology of motivations: Many of them have an intuitive sense to them, and we can often find them explicit in war writings. I wonder, Richard, if you know of any good empirical studies with data on which motives are operative and to what degree in the various participants — front-line fighters, general staff, strategy theorists, politicians, ideologues, and so on.