Interview conducted at Rockford University by Stephen Hicks and sponsored by the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship.

Hicks: Hi. I’m Stephen Hicks. Our guest today is Professor Robert Salvino, who teaches Economics and Entrepreneurship at Coastal Carolina University in South Carolina. He spoke with us today on entrepreneurship and public policy.

One of your initial themes was the importance of entrepreneurship as a driver of the economy. Innovation, business startups, employment, and so forth. And you were pointing out what we actually do know about entrepreneurship. What are the traits that go into entrepreneurial success?

Salvino: Right. When we think about entrepreneurship, we think of a very positive-oriented type of person’s behavior, somebody who is a problem-solver, who sees obstacles and is already thinking about ways to get around those obstacles and accomplish things in spite of barriers that might seem to be very big for the rest of us.

Hicks: Right. And then the question then is: if we want to encourage entrepreneurial behavior, what kind of institutional framework is going to make that happen — or retard it? In your lecture, you made a distinction between a more active approach to public policy, when government is trying to foster entrepreneurship by picking winners and losers, so to speak, and a more indirect approach, where the government sets very general conditions within which entrepreneurship can flourish. What is the difference between these two approaches?

Salvino: An active public policy approach would be literal programs, if you will, that would maybe subsidize start-ups. If you start a small business, there will be credits that will be given to you or job training will be provided, or these types of things, trying to get people to start things. A passive approach to public policy would simply just to allow things to happen. So, have a very favorable business climate in the first place without somebody having to check the regulations and licenses and requirements and see what kind of things they could do. And maybe if you are in this type of industry, you can get better subsidies or things, so, taking that away and letting things just kind of run their course.

Hicks: So the argument there is: you take away particular types of policies, and you create an environment in which entrepreneurship will flourish. Whereas the other is to have that plus particular programs directed to stimulate entrepreneurship. In your talk you also in passing contrasted some regimes around the world that seem actively to discourage entrepreneurship. North Korea is an example. And then the example of cellphones was very striking. What was that?

Salvino: Just a few years ago, Eric Schmidt with Google and, I believe, Josh Cohen went to over to North Korea. They’ve got a book coming out that talks about technology and its role in the spread of prosperity and the changing of oppressive regimes. Just a few years ago, you were not allowed to have a cellphone in North Korea without some sort of authorization. The majority of population did not have a cellphone. Then, they later allowed a million people in a very large country to have a cellphone, but it was a controlled cellphone.

Hicks: If we try to evaluate, then, the two entrepreneurship-friendly approaches, where we assume that entrepreneurship is a good thing and we want to foster it, how do we evaluate whether a more active hands-on government fostering of entrepreneurship works better than a more relaxed government approach?

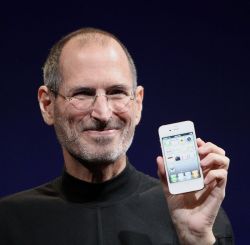

Here you took us through some history, asking us to look at some of the great entrepreneurial success stories, Google, Apple, AT&T earlier, Standard Oil, and so forth. What is the lesson that we learn from those examples, on your reading?

Salvino: Right. Those companies, those technologies — nobody would ever predicted the emergence of these new industries. Ford Motor Company, you would not have been able to identify a group of people whom might have been more likely to be successful. Try to take a group of people from MIT and put them in a room and say: ‘create the next big thing’. People like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates — nobody would have ever identified them as people likely to create the things that they did.

Hicks: So the argument there is just having a culture in which creative, innovative people can do what they want to do, you’re going to get entrepreneurship. And then on the negative side, you had examples like Solyndra, where active public policy trying to promote certain kinds of entrepreneurship blows up in our faces with a huge price. Stay more with that one.

Salvino: Solyndra was, I believe, awarded about $500 million in subsidies through the federal government because they were in a favored industry working in green technologies. And Solyndra went bankrupt within, I believe, a couple of years of forming. If the company, a start-up, had able to get private investors to back them to the tune of $500 million, it’s very unlikely they would have gone bankrupt in two years. So, the difference is between what went into the development of a company like Solyndra versus a company like Apple.

Hicks: Okay. Are we able to step back and cite statistics and say that here is the more relaxed, entrepreneurial-friendly environment, and in that environment, you get a certain number of entrepreneurial successes — Apple, Google, and so forth — but that we’re also going to have a whole lot of failures?

Salvino: Sure.

Hicks: Contrasting that with a government that is more hands-on and tries to pick entrepreneurial winners and losers, they are going to have a lot of failures, but they also have some winners. Are you able to quantify the relative success rate of those two approaches?

Salvino: I haven’t looked at that in my research, but I think if you look at it just from a theoretical perspective and think about resources that are invested in any and each of those, certainly you are going to have many, many failures in the private market with experimentation. But the difference would be the amount of leverage of that investment and the people who suffered as a result of that. If it truly is a market process, the spread of failure is not going to have the negative impact on all of society that something like many Solyndra-type things would.

Hicks: Okay, so we have one 500 million dollar failure that has to be put against then 500 one-million dollar failures, and so forth.

Salvino: Exactly. It is spread throughout the whole system.

Hicks: Now, you also had one particular example of public policy that seemed more indirect, and that was health insurance, where this is not directly intended to have an impact on entrepreneurship or not. But for various other reasons health insurance is a desirable goal, so the government wants to encourage the greater provision of entrepreneurship. But, nonetheless, indirectly it has an impact on entrepreneurship as the example you presented. How does that work?

Salvino: Okay, if we talk of a different types of entrepreneurs, a self-employed individual as one type. So, employer-provided health care as it emerged over time took years and years to grow and become kind of cemented into our culture as an expectation of a good job were good benefits. And so the rate of self-employment just seems to, over the same period of time, been about cut in half. And so, there is a real cost to acquiring  health insurance on your own in this independent market versus when you are with a large company. When you are with a large company that provides the benefit, there are direct policies that make it easier for a large company to provide the benefit to the employee. And so there is a hurdle that is created there, whether it was intended or not.

health insurance on your own in this independent market versus when you are with a large company. When you are with a large company that provides the benefit, there are direct policies that make it easier for a large company to provide the benefit to the employee. And so there is a hurdle that is created there, whether it was intended or not.

Hicks: Okay, so the way this works then is health insurance is a desirable thing for individuals. Government creates a policy that encourages employers to provide health insurance for employees. That makes employment with a company that’s providing health insurance more attractive than self-employment, so self-employment rates go down.

Salvino: Right. That’s kind of the idea that I have looked at and to see if there is a causal relationship between the two. Certainly, we can see at least anecdotally this idea that we place a very high premium on benefits. There was a survey done a couple of years ago throughout the world asking adolescents what do they want when they become adults. And most of them said they want a good job with good benefits. So this has been cemented into our culture.

Hicks: Okay, then public policy responds to that directly.

Salvino: And public policy responds and, in some cases, has helped propel that idea, that expectation.

Hicks: Scaling out then: your proposal was that we should have the more indirect, passive approach to public policy by creating general conditions within which entrepreneurs are free to innovate and experiment. What are those general conditions that you think work best?

Salvino: So, for example, just a sound monetary system that allows us to make long-term contracts and have an idea or expectation of what interest rates are going to be, what the rate of inflation might be, and how that affect us. Property rights, so that when we go into an organization, we form a corporation, we conduct business, we know that our rights are protected and that there is a judicial system that is going to help us solve disagreements and such things. Contract enforcement is another example of an institution that helps. When contracts are not going to be enforced, individuals, investors, or entrepreneurs may be very leery of forming partnerships with people that they may not know very well.

Hicks: You gave the example of China, part way through, as a very striking example. One of things we’re interested in is wealth creation. And wealth creation certainly is an important value if we are already comfortable. Nonetheless, we would like to be more prosperous and make sure our kids are more prosperous.

But wealth creation is important when we think about poverty and places in the world that are still ridden with poverty. You mentioned China as a very striking example. In the last generation, something happened that has never happened before in human history, namely, half a billion people were lifted out of dire poverty into a basic minimum standard of living. Can you track China’s success in doing so to public policy changes in China? And if so, what do you think those were?

Salvino: Right. If you go to China a generation ago, we think of China as a communist country. And still today people associate China with communist regime. But it is going in a different direction than many developed countries in the world. It is kind of backing down from that and going from a completely communist institution to state capitalism. Maybe it’s state-directed capitalism with capital ownership, but still it’s a step in the opposite direction, towards allowing markets to flourish more than previously had. And if we think about it from the perspective of our country, many American businesses over the past generation have put operations in China. And over the period of a generation it has become easier for these businesses to operate in China, to maintain their own property rights.

An individual came and spoke to a group of business leaders in South Carolina a couple of years ago and talked about an operation when they first went into China. In order to start their company they had to give away majority ownership of this subsidiary in China, so they were very leery to do that. And over the past few years, that went away to where they were not any longer required to give away that type of ownership of their company. And as more companies have been able to go into China, not having to give up certain of those property rights, more companies will go in there and conduct business. So there are jobs created in China by American companies and other companies throughout the world. And over a generation that has been one factor, I would say, that has helped to alleviate some of their problems.

Hicks: So China is moving in the right direction?

Salvino: Right, they are moving in the right direction.

Hicks: Thank you for being with us today. Interesting material.

Salvino: Thank you.

[The original video interview with Dr. Salvino follows.]