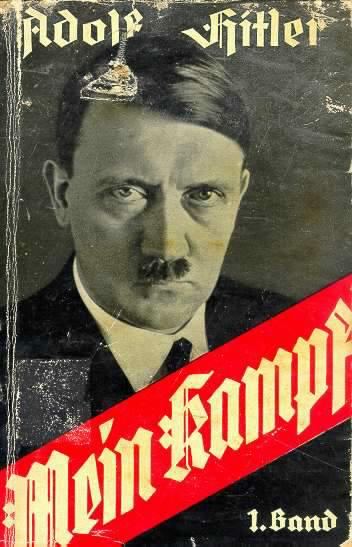

German authorities will allow the republication of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, after decades of censorship.

Decent people can argue that the book is too dangerous to be published. But the fact is that Mein Kampf is too dangerous not to be published.

The great fear is that Hitler’s ideas are not dead and that his book could trigger another horribly pathological social movement. Nationalism and socialism still appeal to many, and combinations of the two ideologies attract new adherents every day in Europe and around the world. (See “The Revival of Nazism in Europe — It’s Not Just Racism.”)

Mein Kampf is available in many editions, in many languages, and online. So the furor over its republication is about the Germans in particular: Can they handle it?

One of many old jokes has one German ask another, “How many Poles does it take to change a light bulb?” The other German replies, “I don’t know. Let’s invade Poland and find out!”

Always fun to poke at the Germans’ historical reputation. But it has been three generations since the end of World War II. There have been major cultural shifts in German attitudes towards militarism, authoritarianism, anti-Semitism, and other elements in the National Socialist package. There is plenty of evidence that today’s German are well above the average in civility and decency. So the post-Nazi cultural training wheels can come off.

Yet beyond the specifics of the German debate, there is a more important general point about prohibiting even the most repulsive of ideas: Censorship weakens our ability to combat them.

Levi Salomon, speaking for the Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism based in Berlin, opposes republication of Mein Kampf: “This book is outside of human logic.”

Perhaps that is true. But it is not outside of human experience. We must understand the “logic” of national socialist beliefs however illogical they turn out to be. Those beliefs continue to have a powerful psychological and social appeal to many, so it is crucial that every generation know exactly what they are, why they attract many — and how to fight them.

The Nazis were not just some crazy guys who somehow lucked into power. For too long a cartoonish understanding of National Socialism has held sway in the public mind.

But consider this. For years before the Nazis took over, three Nobel-Prize winners — Johannes Stark, Gerhart Hauptmann, and Philipp Lenard — supported the Nazis.

Also before the Nazis came to power, many intellectuals with Ph.D. degrees from the best German universities wrote books supporting national socialist ideology. Among them were the historian Dr. Oswald Spengler, who published the bestselling The Decline of the West in 1918. Spengler was the most famous German intellectual in the 1920s. The legal theorist Dr. Carl Schmitt wrote books that are still recognized as twentieth-century classics. Political theorist Moeller van den Bruck published The Third Reich in 1923, which was a big seller throughout the 1920s. And the philosopher Dr. Martin Heidegger, thought by many to be the most original philosophical mind of the century, actively supported the Nazis in theory and in practice.

Many of those big-brained supporters of national socialism were extremely well read and saw themselves as disciples of George Hegel, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche — and as doing the vital, idealistic work of applying those abstract philosophies to practical politics. (See my Nietzsche and the Nazis for details.)

So the problem is not Adolf Hitler alone. And if we are to censor dangerous writings that led to Nazism, the list is long.

Also important is the fact that many millions of Germans voted for the Nazi party. In the critical democratic election of 1933, the Nazis won 43% of the vote — more than the next three parties combined. (In second place were the Socialists, and in third place were the Communists, which also speaks much about the political-intellectual climate of the time.)

The electoral success of the Nazis was also not the product of a set of ideas in books alone. In building their movement, the Nazis used cutting-edge principles of marketing, logistics, and administration. They applied new theories of psychology and sociology to build upon a core movement of hundred of devoted activists and turned it into a mass movement of millions of followers. Yet we don’t want to censor books on effective logistics, marketing, and social psychology.

So we have some hard questions: Why did so many top intellectuals agree with National Socialist ideas? Why did so many volunteers and donors and professionals devote their energies to creating an awesome political movement? Why did millions of German citizens vote — often enthusiastically — for the Nazis? Were they all just stupid/depraved/insane?

No, they were not. Whether we like the fact or not, National Socialism embodies a deep philosophy of life — and that is what explains its power. One might argue that Nazi philosophy is not logical and rational. I will agree. Yet few philosophies are. One might argue that Nazism, if embraced fully, leads to psychosis. I will agree again. Yet that also is true of many philosophies.

But is neither logical nor rational nor sane to ignore a set of ideas that continues to animate movements around the world. Suppressing dangerous ideas is much more dangerous than fighting them openly.

A free society can work only if most of its members understand what principles a free society depends upon and why they are better than the alternatives. That presupposes that they know what the alternatives are.

So there are no short cuts in our ongoing cultural education. Every generation must discuss and debate the great ideas — true and false, known and possible, healthy and dangerous — and become intellectually armed so as to defend and advance liberal civilization.

Sometimes the urge to censor focuses on the symbolism of allowing evil books to be published. Not censoring Mein Kampf, for example, is a statement by the authorities that they consider national socialist ideas to be within the range of acceptable opinion.

But we should remember that a free society rejects the idea that it is up to the authorities to decide what opinions are acceptable. That’s our job, each of us individually.

In his dissenting opinion in a classic case in American censorship, Justice Potter Stewart made this perceptive remark: “Censorship reflects a society’s lack of confidence in itself.”

There is an important symbolism built into encouraging robust free speech: We can handle it.

So let us strive for that self-confidence. We have the smarts and the character to deal with the Adolf-Hitler-wannabes, as well as their clever theoreticians.

[This article was originally published in English at EveryJoe.com and in Portuguese at Libertarianismo.org.]