[With Trump-strategist Steve Bannon all over the news, here’s a re-post of my one encounter with the Breitbart news and commentary site he headed.]

What can I say?

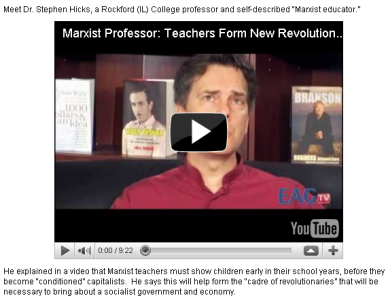

According to Andrew Breitbart’s Big Government website, Professor Stephen Hicks of Rockford College is a Marxist devoted to educating cadres of revolutionaries.

Many people posted/emailed the Breitbart site about the error. Eventually I received a note of apology from the author and the post was retracted. This Internet Wayback Machine archive of the post contains some … refreshing … comments and suggestions from sensitive and informed readers.

A good case of an under-researched post that jumps to a very wrong conclusion. (Thanks to Hal Hollis for the pointer.)

Here is the full context for the video clip — my fifteen-part series of lectures on the Philosophy of Education, in which I present many philosophies, Marxism included.

Now I wish I had a photo-shopped image of myself with a red beret and a t-shirt saying something nasty about capitalism. That would be proof indeed.

For a good statement of my actual philosophy of liberal arts education, I recommend Chapter 2 of John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, a key portion of which I excerpt here:

‘There is a class of persons (happily not quite so numerous as formerly) who think it enough if a person assents undoubtingly to what they think true, though he has no knowledge whatever of the grounds of the opinion, and could not make a tenable defence of it against the most superficial objections. … [T]his is not the way in which truth ought to be held by a rational being. This is not knowing the truth. Truth, thus held, is but one superstition the more, accidentally clinging to the words which enunciate a truth. …

‘There is a class of persons (happily not quite so numerous as formerly) who think it enough if a person assents undoubtingly to what they think true, though he has no knowledge whatever of the grounds of the opinion, and could not make a tenable defence of it against the most superficial objections. … [T]his is not the way in which truth ought to be held by a rational being. This is not knowing the truth. Truth, thus held, is but one superstition the more, accidentally clinging to the words which enunciate a truth. …

‘If the cultivation of the understanding consists in one thing more than in another, it is surely in learning the grounds of one’s own opinions. Whatever people believe, on subjects on which it is of the first importance to believe rightly, they ought to be able to defend against at least the common objections. But, some one may say, “Let them be taught the grounds of their opinions. It does not follow that opinions must be merely parroted because they are never heard controverted.” …

‘But when we turn to subjects infinitely more complicated, to morals, religion, politics, social relations, and the business of life, three-fourths of the arguments for every disputed opinion consist in dispelling the appearances which favour some opinion different from it. The greatest orator, save one, of antiquity, has left it on record that he always studied his adversary’s case with as great, if not with still greater, intensity than even his own. What Cicero practised as the means of forensic success, requires to be imitated by all who study any subject in order to arrive at the truth. He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination. Nor is it enough that he should hear the arguments of adversaries from his own teachers, presented as they state them, and accompanied by what they offer as refutations. That is not the way to do justice to the arguments, or bring them into real contact with his own mind. He must be able to hear them from persons who actually believe them; who defend them in earnest, and do their very utmost for them. He must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form; he must feel the whole force of the difficulty which the true view of the subject has to encounter and dispose of; else he will never really possess himself of the portion of truth which meets and removes that difficulty. Ninety-nine in a hundred of what are called educated men are in this condition; even of those who can argue fluently for their opinions. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know: they have never thrown themselves into the mental position of those who think differently from them, and considered what such persons may have to say; and consequently they do not, in any proper sense of the word, know the doctrine which they themselves profess. They do not know those parts of it which explain and justify the remainder; the considerations which show that a fact which seemingly conflicts with another is reconcilable with it, or that, of two apparently strong reasons, one and not the other ought to be preferred. All that part of the truth which turns the scale, and decides the judgment of a completely informed mind, they are strangers to; nor is it ever really known, but to those who have attended equally and impartially to both sides, and endeavoured to see the reasons of both in the strongest light. So essential is this discipline to a real understanding of moral and human subjects, that if opponents of all important truths do not exist, it is indispensable to imagine them, and supply them with the strongest arguments which the most skilful devil’s advocate can conjure up.’

Were you typing this post wearing a Che t-shirt? ha ha!

I should have worn one.