Art begins in the mind of a creative individual. The artist takes his significant experiences and thoughts as raw material and creates a perceptual embodiment for them. Each artist makes independent judgments about which of his experiences and thoughts are significant. And to the best of his ability and with his unique style, each artist employs the techniques of his perceptual medium of choice. The result is an object that, at its best, has an awesome power to exalt the senses, the intellects, and the passions of those who experience it.

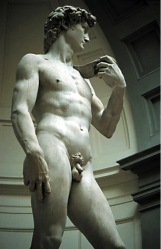

Those individuals who over the centuries accepted art’s calling developed it into a vehicle that called upon the highest insights of the human creative vision and demanded exacting skill. The names that evoke in us a sense of greatness—Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, Vermeer —stand for those individuals who expanded the range of themes and subjects and developed the repertoire of techniques available to the next generation of artists. Their achievements created the status of the artist as not merely a visionary or a craftsman, but as a special individual in whom both vision and craft are integrated and heightened.

—stand for those individuals who expanded the range of themes and subjects and developed the repertoire of techniques available to the next generation of artists. Their achievements created the status of the artist as not merely a visionary or a craftsman, but as a special individual in whom both vision and craft are integrated and heightened.

But by about the middle of the nineteenth century, the art world began to lose its confidence. The art world’s symptoms of decline were part of the broader intellectual world’s slipping into a sense that progress, beauty, optimism, and genuine originality were no longer possible.

The causes of the sense of decline were many. The increasing naturalism of the nineteenth century led, for those who had not shaken off their religious heritage, to a feeling of being alone and without guidance in a vast, empty universe. The rise of philosophical theories of skepticism and irrationalism led many to distrust their cognitive faculties of perception and reason. The development of scientific theories such as evolution and entropy brought with them pessimistic accounts of human nature and the destiny of the world. The spread of liberalism and free markets caused their opponents on the political left, many of whom were members of the artistic avant garde, to see political developments as a series of deep disappointments. And the technological revolutions spurred by the combination of science and capitalism led many to project a future in which mankind would be dehumanized or destroyed by the very machines that were supposed to improve their lot.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the nineteenth-century intellectual world’s sense of disquiet had become a full-blown anxiety. The artists responded, exploring in their works the implications of a world in which reason, order, certainty, dignity, and optimism seemed to have disappeared.

The works that are the iconic pieces of twentieth century art express the minds of the great names that created them.

Twentieth-century art is Pablo Picasso’s fractured world populated by vacant-eyed, disjointed beings. It is Edward Hopper’s emotionally out-of-tune men and women in bland, worn settings. It is the predatory horror of Willem de Kooning’s Woman series. It is Salvador Dali’s surreal world in which the distinction between subjective dream states and objective reality is obliterated.

The twentieth-century world is also the story of its own self-elimination. While Picasso and Munch looked at reality and reported their depressed observations, others retreated from the world and proceeded to strip away from art anything that they could. On the grounds that other media such as photography and literature reproduced reality and told stories, many eliminated as much content as they could from their works. Art came to be a self-contained study of dimension, color, and composition. But the reductionist, stripping-away game led quickly to challenges even to those features. In the sterile color studies of Piet Mondrian and Barnett Newman, any sense of a third dimension disappeared.

The art world had reached a dead end. When it looked out at the world through the eyes of Picasso and Munch, it saw nothing of value. When it looked at what the reductionists had produced, it saw that nothing uniquely artistic had survived. Collectively, the leading members of the art world had decided that art has no content, that it has no special media or techniques, and that the artist has no crucial role in the process. Art became nothing—or a statement of nothingness.

The summary conclusion was announced, infamously, by Marcel Duchamp.

Asked to submit something for display in 1917, Duchamp sent a urinal. Duchamp of course knew the history of art. He knew what had been achieved—how over the centuries art had been a powerful vehicle that called upon the highest development of the human creative vision and demanded exacting technical skill; and he knew that art had an awesome power to exalt the senses, the minds, and the passions of those who experience it. Duchamp reflected on the history of art and decided to make a statement.

Art by its nature is about the significant. To the extent that art is an expression of the artist’s being, it expresses what the artist thinks and feels to be significant. To the extent that art is an act of communication, it is a statement to an audience of what the artist thinks and feels to be important. When an artist decides to devote a week, a month, or a year or more of his life to creating This rather than That—he is saying that This is worth his time and effort. When the artist presents the results of his efforts to an audience, he is telling them that his creation is worthy of the time and effort of their contemplation. We do not waste our time on the insignificant or ask others to waste theirs—unless we wish to express the significant belief that nothing is significant.

Duchamp and the others have become the iconic figures of recent art history. Through them, the story of the art world is a story of self-conscious disintegration.

Once, however, everything has been disintegrated, every artist has a choice. He can choose to play the current game of cynicism and despair, hoping, at best, to introduce a minor variation here and there. Or he can look afresh at the world and rediscover in it the potential that earlier great artists pointed us toward.

Much of the art world is currently a long way from building upon Michelangelo’s powerfully stylized human forms, Rembrandt’s skill of characterization, Vermeer’s exquisite use of light. Though closer in time, much of it is also a long way from the majesty in the works of Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Church, the elegance of John Singer Sargent’s paintings or the exuberance of Frederic Remington’s.

Though closer in time, much of it is also a long way from the majesty in the works of Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Church, the elegance of John Singer Sargent’s paintings or the exuberance of Frederic Remington’s.

The artist is not an archaeologist, and the point is not to resurrect and imitate the past. The point is that the world they saw and a whole lot more is still out there.

The artist, like every thinking and passionate human being, has the power to decide whether to accept the assumptions of the recent past and work within them, or whether to strike out on his own, questioning those assumptions and actively seeking alternatives to them. Every artist, in his work, expresses the deepest choices he has made. That power of expression is what compels some of us to be artists in the best sense, and it is what attracts those of us who are not artists to their creations. The strategic choice of what to express and how, accordingly, is everything.

[“Post-Postmodern Art” was originally published in The Newberry Manifesto, 2001. Also available in a reprint version with images of the relevant works, as well as a Slide show version with images. Serbo-Croatian translation by Alma Causevic. Arabic translation by Moin Jaffar Mohammed.]

Pingback: New Book: The Good, Postmodernism, and Beyond – Michael Newberry