What happens to education when it is politicized?

Now that we have a new administration, led by Donald Trump, and a new secretary of education, Betsy DeVos, here is an updating of a Public Choice analysis of our mixed government-private education system came to be. The following is based in part by E. G. West’s important Education and the State (1965; third edition 1994), a classic early text applying public choice analysis to education.

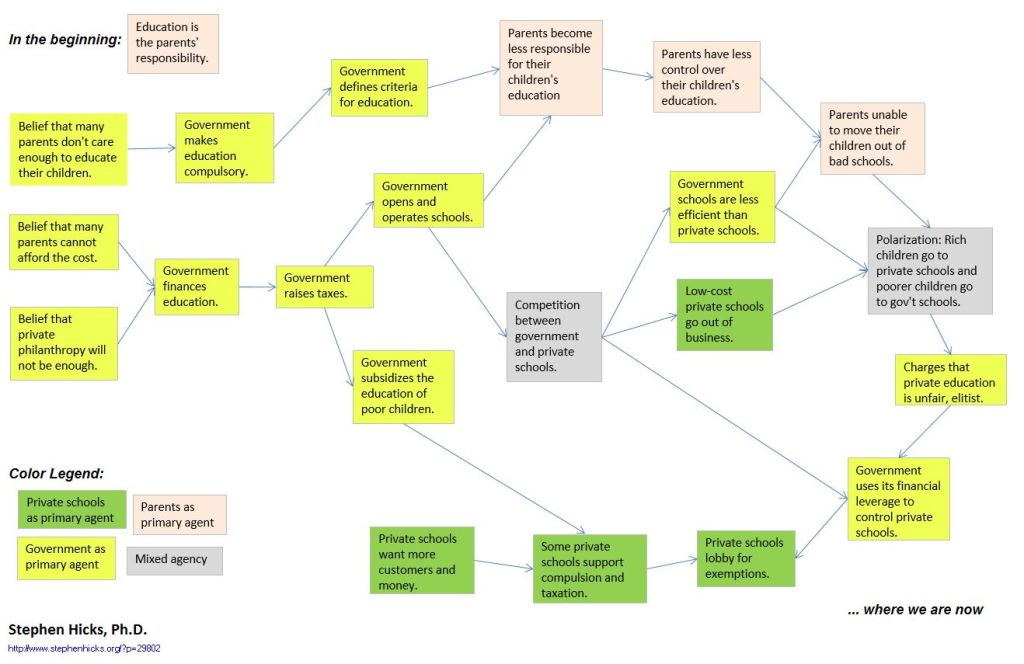

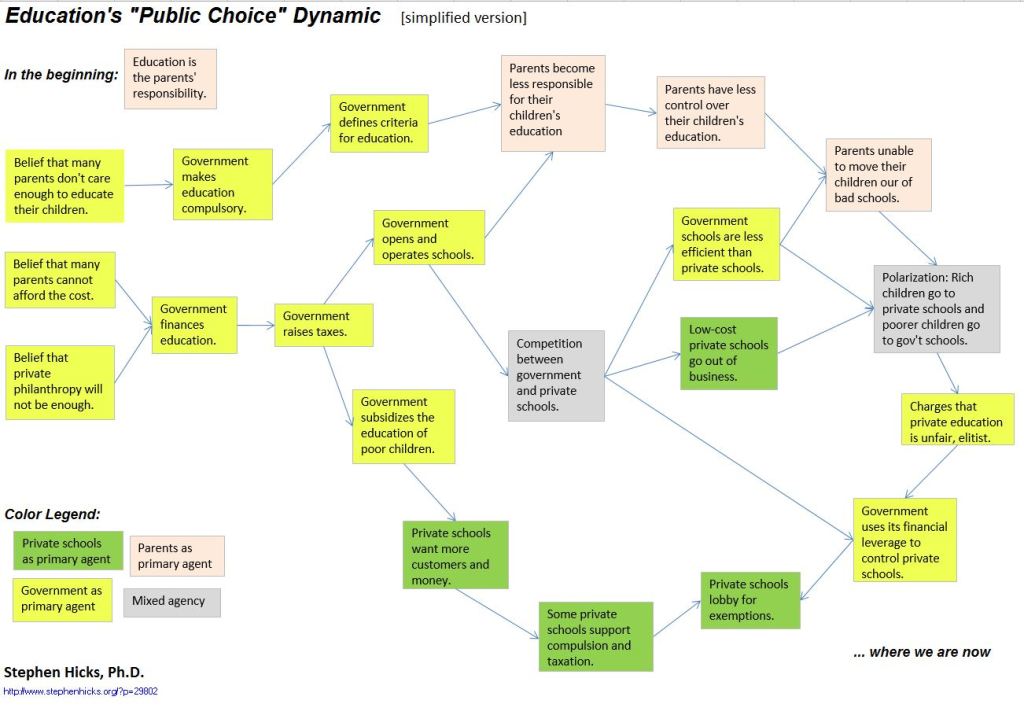

Arguments for government involvement in education are many. They include the views that many parents cannot afford to educate their children, that private philanthropy cannot make up the deficit, that too many parents don’t care enough about education, and more.

But government involvement in education also has risks:

* Less parental control over and responsibility for their children.

* The driving out of low-cost private schooling.

* Adding to class-warfare tensions.

* Lobbying by private schools for exemptions and special favors.

A few lines of development are captured in this flowchart, which is here in Excel spreadsheet and JPEG image versions.

This simplified version does not include the role of bureaucracy, unions, the lessened accountability, or the use of education as a bait-and-switch tactic for tax increases, for example. So please feel welcome to add to the chart and otherwise modify for your own purposes.

I think it would help if we took a step back and asked WHY education is important.

The reality is that education is a way to provide skills necessary to earn a living. Some, like scientists and bookworms, make education a pastime as well, but that’s no more significant than any other pastime–the idea that “life-long learning” is a serious goal of education should be taken as seriously as the idea that education is there in order to create football teams. What matters in the end is whether the student, upon graduation, can earn a living or not.

It can be argued that in our culture a tremendous variety of information is necessary merely to function, and that’s true to an extent. However, that has always been true. A hunter/gatherer tribe required its children to know several hundred different plants, their uses, how to prepare them, when to gather them, etc.

Schools are a convenient way to provide a tremendous amount of information, but I see no reason to assume they’re the only way. In reality the very concept of a school (as we know it today) is new–universities are the product of Abelard’s work, and schools for younger children quite often consisted of traveling teachers. Many children gained most of their education from on-the-job training: farming, for the most part, but there were other industries as well. (Glass blowing was a big one until beer brewers automated their systems.)

I’m not saying we should go back to the educational standards of the 1700s en mass. What I am saying is that we should not fall into the Is/Ought Fallacy. Just because schools exist the way they do is no reason to assume this is the best, or even a particularly GOOD, way to train someone. Other viable methods have existed, and deserve serious consideration. This is particularly true in an era where anyone who wishes to do so may download lectures on literally any topic, at all levels, from grade school to post-doctoral.

Once you start asking that sort of question, the whole setup becomes even less desirable. The main force government exerts on education is to enforce uniformity (except for the children of those who govern and a few others, of course). And it’s not obvious that uniformity is desirable.