In 1770, tensions were high between the American colonists and their British rulers. Anxious soldiers confronting an angry mob precipitated the Boston Massacre. Eight soldiers were then put on trial for murder.

The lawyer John Adams was a strong American patriot, yet he took on the defense of the British soldiers. His purpose was explicitly to set an example: that the rule of law could and would prevail despite the political passions of the moment. Americans would do justice. Adams argued that six of the eight were not guilty, and the jury agreed. Two soldiers were convicted of manslaughter on the basis of evidence that they had fired directly into the crowd.

The lawyer John Adams was a strong American patriot, yet he took on the defense of the British soldiers. His purpose was explicitly to set an example: that the rule of law could and would prevail despite the political passions of the moment. Americans would do justice. Adams argued that six of the eight were not guilty, and the jury agreed. Two soldiers were convicted of manslaughter on the basis of evidence that they had fired directly into the crowd.

(A moving account of the events appears early in the excellent miniseries John Adams.)

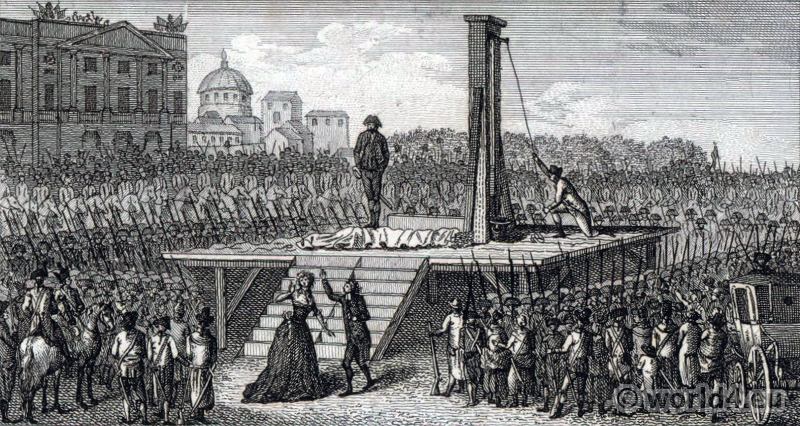

To that I contrast this account of Jacobin revolutionary justice, taken from J. M. Thompson’s Robespierre and the French Revolution, from which I quote at length from pages 108-109:

“The Law of the 22nd prairial (June 10, 1794) … declared that:

‘The Revolutionary Tribunal is instituted to punish the enemies of the people. The enemies of the people are all those who aim at destroying public liberty, either by force or by trickery.’ It then went on to instance eleven kinds of conduct that would fall under this general condemnation—drawn in terms so wide that hardly any suspect could escape the charge of treason (anti-civisme). Article 7 then laid it down that the only sentence the court could pass, in case of conviction, was death; and Article 8 that sufficient evidence for the death sentence could be found in ‘any kind of documents, material or moral, written or spoken, which naturally claim the assent of any just and reasonable mind’; explaining this vague account by adding: ‘The standard of judgment [i.e. the decision as to what is good evidence] is the conscience of jurymen enlightened by patriotism: their aim is the triumph of the Republic and the ruin of its enemies.’ Finally, lest anyone might still suppose that the duty of the court was to try, and not merely to convict, Article 13 provided that if the jury thought it unnecessary to call witnesses, they could dispense with them; and Article 16 that patriotic jurymen were sufficient counsel for patriots wrongly accused, and that ‘as for conspirators, the law does not allow them to have counsel at all.’”

“This Prairial Law, under which the number of cases heard was more than doubled, and the number of executions went up from 346 in May to 689 in June and 936 in July, has not unnaturally become notorious for its wholesale guillotining of persons deprived of any fair chance of defending themselves; and historical emphasis has been laid on the outstanding miscarriages of justices. But at the time this aspect was thought little of, compared with what might seem minor issues.”

An abstract way of putting the difference is this:

An abstract way of putting the difference is this:

The American leaders of the 1770s, John Adams included, were Lockean and Beccarian and committed to individual justice. The French leaders of the 1790s, Maximilien Robespierre and Saint-Just included, were Rousseauean and committed to collectivist justice.