Sparked by some recent conversation, here again is a striking quotation from Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions:

“Every civilization of which we have records has possessed a technology, an art, a religion, a political system, laws, and so on. In many cases those facets of civilization have been as developed as our own. But only the civilizations that descend from Hellenic Greece have possessed more than the most rudimentary science. The bulk of scientific knowledge is a product of Europe in the last four centuries.” (2nd edition, pp. 167-168)

Two follow up questions about Kuhn’s claim:

Is he right?

If so, what about classical Greek culture enabled this great influence?

Also, is it accidental that the postmodernists, agreeing with Heidegger, seek to devalue the scientific enterprise? For example, from Introduction to Metaphysics (1935):

“[T]he spirit of poetry (only authentic and great poetry is meant) is essentially superior to the spirit that prevails in all mere science.” (p. 26)

Note that science rates a “mere”.

And the Heideggerian claim in “What is Metaphysics?” (1929) that Greek thought was a fateful mistake — here, for example, on the “logic” that underlies scientific method:

“Why do we put this word [‘logic’] in inverted commas? In order to indicate that ‘logic’ is only one exposition of the nature of thinking, and one which, as its name shows, is based on the experience of Being as attained in Greek thought.”

Via the Greek way of thinking, we get logic and science. In the modern world, those make possible the Enlightenment world in which we still live. But, our anti-modern critics argue, the modern Enlightenment is what we need to get beyond — we should be post-modern. But perhaps it’s more accurate to characterize the critics as saying that we need to get back to where we were before the Greeks’ innovations took us down the wrong path. And that, intriguingly, means that the post-modernists would better be described as pre-modernists.

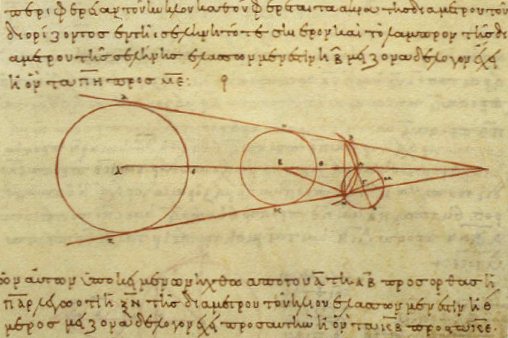

(The image is from Aristarchus, one of the great Greek astronomers, from a tenth-century CE copy of his manuscript.)

I have never understood the concept that science is somehow inferior to poetry.

Yesterday I was at an industrial site, and had to wait on hold with a company’s IT’s department. While I did so, I watched the scum on the pond (industrial byproducts floating to the surface, forming a film on it) pile up as the flow crashed the scum into an obstruction. This caused me to re-think my understanding of mountain formation and the breakup of continents. A fascinating concept that I’m still playing with.

No poet on Earth would find beauty in the scum on an industrial pond. I mean, my observations are inherently poetic–specifically metaphorical–but poets, sadly, seem to miss them. A scientist who dabbles in poetry can play with the concepts (see Eurasmus Darwin), but they have to be a scientist first to comprehend the beauty of these systems, it seems.

Any idiot on Earth can see the beauty of a rainbow, or a flower, or the like. Poetry didn’t teach us to appreciate any of those. Science, in contrast, taught us the beauty in the mundane.

Well said, James.