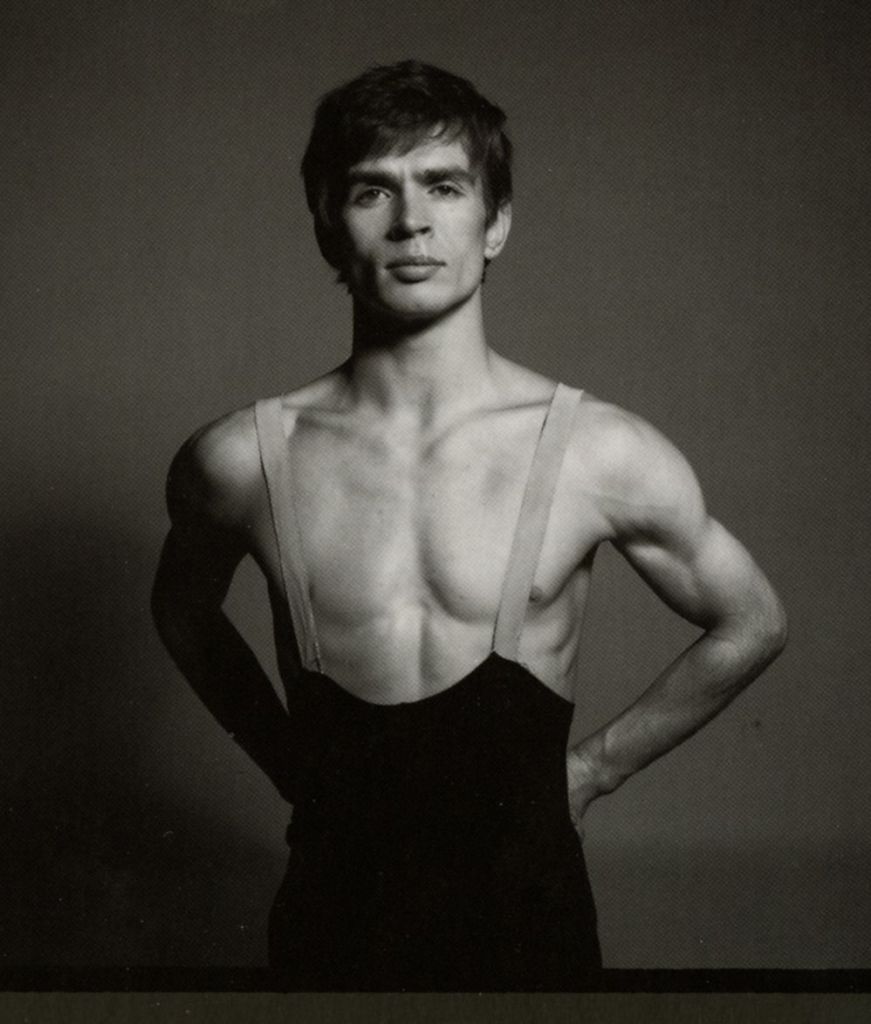

What made Rudolf Nureyev an outstanding dancer? Some insights from biographer Julie Kavanagh’s Rudolf Nureyev: The Life.

What made Rudolf Nureyev an outstanding dancer? Some insights from biographer Julie Kavanagh’s Rudolf Nureyev: The Life.

On his focus as a student and his eliminating non-essentials from his life: “I’ve always tended to reject everything in life which doesn’t enrich or directly concern my single dominating passion.” A fellow student noted: “When Rudolf arrived in Leningrad, there was only one thing on his mind: to improve his dancing.” (38)

To become his best, he absorbed any art and literature he could visit or get his hands on: he “went to concerts at the Philharmonic Hall; saw Shakespeare performed at the Gorky Theater; and, to study different acting techniques, even sat through mediocre propagandist plays at the Pushkin Theater, staged by an artistic director who had ‘sold his soul to the devil.'” (39)

Even among the passionate-about-dance community, Rudolf was

“regarded by colleagues as an alien being, living a different existence and interested only in museums, theaters, the Philharmonic Hall, art books, and musical scores. ‘He seemed like some kind of fanatic to everyone,” said one. (43)

At school, Rudolf’s independence caused repeated clashes with the school’s director, Shelkov, a traditionalist authoritarian of petty character: “nothing Shelkov did could make Rudolf conform. He refused to become a member of Komsomol, the junior organization of the Communist Party, to which most of his colleagues belonged, and he disregarded countless school rules.”

Shelkov reacted by obstructing Nureyev whenever he could and even resorting to physical compulsion: “Shelkov was fanatical about observing old Imperial School traditions: Collars must be white and buttoned to the neck, pupils must stop and bow when passing a member of the staff in the corridor. Once, when Rudolf walked past him without making the traditional obeisance, the director called him back and, taking hold of the dancer’s hair, forced his head down over and again, shouting, ‘Bow! Bow! Bow!‘” (45-46)

Yet some of Nureyev’s teachers were outstanding — sensitive, expert, benevolent, and wise. One such was Alexander Pushkin, who taught dancing as as psychological expression and not merely as bodies moving well technically:

“In his class you could see boys, even in their teens, moving individually in the way that patterns of speech separate one person from another. With dance it’s the same thing: you have to find that individuality, that internal understanding of phrasing. Pushkin was teaching boys to make their own decisions: creating thinking dancers.” (44)

I recently saw and enjoyed The White Crow (2018), directed by Ralph Fiennes, who also plays the role of Alexander Pushkin, Nureyev’s teacher, in the film.

Related:

How great artists become great.

More on how great artists become great.

Creative geniuses as selfish — Beethoven version.

Creative geniuses as selfish — Richard Wagner version.

Creative geniuses as selfish — Maria Callas version.

Creative geniuses as selfish — Rachmaninoff version.