Steven Sanders, Ph.D., is professor of philosophy at Bridgewater State University, Massachusetts.

“Hicks writes about modern European philosophy and the Anglo-American tradition with sophistication and an eye for the thought-revealing anecdote.”

Reason Papers 28 (Spring 2006): 111-124.

Stephen R. C. Hicks’s Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault

A Discussion

Steven M. Sanders

Bridgewater State College

I. Introduction

Readers of Explaining Postmodernism will find much to reflect upon and engage with in the pages of this lucid study of the background, themes, and consequences of postmodernist thought and practice. The book has already received lavish praise from Reason Papers founding editor Tibor R. Machan and it is easy to see why. With clarity, concision, and an engaging style, Hicks exposes the historical roots and philosophical assumptions of the postmodernist phenomenon. More than that, he raises key questions about the legacy of postmodernism and its implications for our intellectual attitudes and cultural life.

Explaining Postmodernism is broad in scope, moving with ease from Rousseau and Kant to Derrida and Rorty. Hicks writes about modern European philosophy and the Anglo-American tradition with sophistication and an eye for the thought-revealing anecdote. In addition to tackling major thinkers including Rousseau, Kant, Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger, Hicks gives us insightful glimpses into a number of second-tier figures who are still less widely discussed than perhaps they should be. The book is studded with clarifying distinctions and is written in a style that seamlessly integrates primary material into the narrative, making explicit the common themes underlying postmodernism in philosophy, politics, and the arts.

This is not a purely historical work. It is also a critique, and in many places it is vigorously polemical. Hicks make a commendable effort to provide a balanced account of the philosophers he discusses, but his emphasis is clearly on aspects of their thought of greatest relevance to the development of postmodernism. In any case, it takes courage for a philosopher at an American university to say some of the things Hicks says in this book. One need only note the fate of Lawrence Summers to see how very risky it can be to transgress Left orthodoxy in the academy. As Steven Pinker reports, when the president of Harvard University had the temerity to raise the question of the possibility of innate sex differences at a conference on gender imbalances in science, eminent MIT biologist Nancy Hopkins stormed out of the room to avoid, she said, fainting or becoming physically ill—thereby, in the words of Harvey Mansfield, conforming to the traditional stereotype of women as “emotional” at the same time as she denounced it. The National Organization for Women called for Summers’s resignation and more than 100 Harvard faculty members signed a letter criticizing him. In a follow-up story on the controversy, Jason Zengerle makes it clear that Harvard faculty Leftists had other grievances against Summers, including his paean to patriotism a month after the September 11th terrorist attacks, his decision to rescind a Sixties-era policy prohibiting students from citing ROTC service in their yearbook, his opposition to the campaign to force Harvard to divest its portfolio of companies that do business in Israel, and his confrontation with African-American studies professor Cornel West over the quality of West’s scholarship, a confrontation widely reported at the time to have led West to decamp to Princeton. Summers’s mea culpas in the aftermath of the response to his remarks were to no avail. At a meeting on March 15th, the faculty passed a resolution declaring a lack of confidence in the president. If these accounts of “L’Affaire Larry” are to be believed, many among Harvard’s faculty hardly covered themselves in glory, and Hicks’s book helps to explain why.

Hicks organizes his material with historical insight and analytical finesse around a central thesis: “The failure of epistemology made postmodernism possible, and the failure of socialism made postmodernism necessary” (i, emphasis in text). The six chapters that make up Explaining Postmodernism can be divided conveniently into two groups of three chapters, each group pivoting on a hypothesis about postmodernism. The articulation and defense of these hypotheses, together with a delineation of their implications for philosophy, science, politics, ethics, education, and the arts is the raison d’etre of Explaining Postmodernism and the basis of its importance. In what follows I will discuss central themes in Hicks’s book (without claiming to do justice to the vast range of topics it takes up): Kant and postmodernist epistemology; postmodernist politics and the Left; and postmodernist nihilism. First, however, let me say something about Hicks’s view of postmodernism as a reaction to the Enlightenment project.

II. What is Postmodernism?

The terms “postmodern,” “postmodernism,” and “postmodernist” are associated with disciplines as different as literary criticism, architecture, painting, and philosophy and have come into use in these disciplines at different times and for different purposes. It is therefore a matter of some dispute whether postmodernism is best described as an historical period stretching from the 1960’s to the present, a mosaic of moods, motifs, and themes, a distinctive style, sensibility, or point of view, or all of these things. Even when we confine our attention to the terms as they show up in philosophical contexts, we find a multiplicity of uses. Philosophers have characterized postmodernism as a set of theses, as a “condition,” in the words of Jurgen Habermas, in which there is “a crisis of modernity,” and even as “an activist strategy.” The great dangers, of course, are either to be so overwhelmed by the many forms postmodernism has taken that one is unable to offer a useful characterization at all, or to make postmodernism appear more monolithic than it is. Fortunately, Hicks has largely avoided these extremes. Rather than try to settle controversies about its contested boundaries, he proceeds with an account of postmodernism as a comprehensive intellectual and cultural movement defined by certain fundamental metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical premises that brought together intellectual developments in the mid-twentieth century in many areas including philosophy, politics, and the physical sciences (21). Postmodernism is anti-realist in its metaphysics, for it denies that we can speak meaningfully of an independently existing reality. It is relativist if not skeptical in its epistemology, rejecting reason, or anything else, as a means of acquiring objective knowledge. It is collectivist and social-constructivist in its accounts of human nature, activist in its ethics and politics, and noisomely avant-gardist in its aesthetics.

Any family of views calling itself post-modernist positions itself historically and conceptually as a response to “modernism.” In philosophy, the essential modernist figures are Bacon, Descartes, and Locke with their philosophical naturalism, confidence in reason, and individualism (7). In Hicks’s view, “The battle between modernism and the philosophies that led to postmodernism was joined at the height of the Enlightenment”—with its innovation and progress in science and technology, its liberal politics and its free markets, which were all made possible by a confidence in the power of reason (22-23). Hicks’s discussion of the epistemology and political philosophy of these paradigms of modernism helps us to identify what postmodernists see themselves as negating and transcending. Summarizing this discussion, Hicks writes:

Postmodernism’s essentials are the opposite of modernism’s. Instead of natural reality—anti-realism. Instead of experience and reason—linguistic social subjectivism. Instead of individual identity and autonomy—various race, sex, and class group-isms. Instead of human interests as fundamentally harmonious and tending toward mutually-beneficial interaction—conflict and oppression. Instead of valuing individualism in values, markets, and politics—calls for communalism, solidarity, and egalitarian restraints. Instead of prizing the achievements of science and technology—suspicion tending toward outright hostility (14-15).

Postmodernism rejects, or is deeply suspicious of, truth, objectivity, and progress, and is characterized by a distinctive anti-science, anti-capitalist mentality. Postmodernists are united by both a shared philosophical history and a shared conception of human nature—or at least agreement about what our “core feelings” are: “dread and guilt” (Kierkegaard and Heidegger); “alienation, victimization, and rage” (Marx); “a deep need for power” (Nietzsche); and “a dark and aggressive sexuality” (Freud). As Hicks observes, postmodernists divide over the question whether these core feelings are socially or biologically determined, but “in either case, individuals are not in control of their feelings: their identities are a product of their group memberships, whether economic, sexual, or racial,” and since these vary, with no objective standards to which we can submit our alternative and conflicting perspectives, “group balkanization and conflict must necessarily result” (82).

As Hicks makes clear, far from emerging fully developed from the work of a few Sixties-era French theorists, postmodernism has a distinguished lineage that can be traced back to Kant, Rousseau, and Marx. Its influence has been felt not only in philosophy, where its leading strategists include Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Francois Lyotard, and Richard Rorty, but also in literary criticism and legal theory (Stanley Fish, Frank Lentricchia), psychology (Jacques Lacan), philosophy of science (Paul Feyerabend, Luce Irigaray), architecture (Charles Jencks, Robert Venturi, Michael Graves), and literature and the arts (Thomas Pynchon, Laurie Andersen, Cindy Sherman, Damien Hirst).

III. Kant and Postmodernist Epistemology

Hicks’s first hypothesis about postmodernism is that:

Postmodernism is the first ruthlessly consistent statement of the consequences of rejecting reason, those consequences being necessary given the history of epistemology since Kant (81, emphasis in text).

To understand Kant’s significance as a precursor of postmodernism, Hicks looks at Kant’s prominence on the broad horizon of the Enlightenment, whose most influential thinkers were sustained by the rationalist hope that the use of reason would be transformative of life. The advancement of science and the growth of knowledge were to lead to progress, prosperity, and perfectibility. Nowhere is this eighteenth century optimism more dramatically shown to be problematic than in the writings of Rousseau. Hostile to the very science with which most of his contemporaries were infatuated, Rousseau challenged the faith in this wonderful engine of progress in a “Counter-Enlightenment” critique of reason that had an important influence on Kant (24ff.). Not only do we not need all that we can obtain by dint of our reason; but the multiplication of wants in the wake of the application of our inventiveness leaves us dissatisfied and dependent, at odds with ourselves and incapacitated for living well. “As the conveniences of life increase and luxury spreads the virtues disappear; and all this is an effect of the sciences and the arts.” Thus was Rousseau intent on showing the problematic features of living with the strategy of progress. It is a measure of his importance that this attitude remains with us today in that blend of influences from which postmodernism derives its peculiar appeal: Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, and Heidegger.

Kant’s is the paradigm case of rationalist epistemology, and its failure is the basis of the subsequent rejection of reason typical of postmodernist thinkers. Two of Kant’s key assumptions are that “the knowing subject’s having an identity is an obstacle to cognition” (37), and that “abstractness, universality, and necessity have no legitimate basis in our experiences” (38). These assumptions mark Kant as “the decisive break with the Enlightenment and the first major step toward postmodernism” (39). Why is this? Because they amount to the idea that “reason is in principle severed from reality” (41). According to Hicks, Kant decisively rejected objectivity. Once one thus separates reason from reality, “the rest is details—details that are worked out over the next two centuries. By the time we get to the postmodernist account, reason is seen not only as subjective, but also as incompetent, highly contingent, relative, and collective” (42).

Postmodernism, thus, is the result of this Counter-Enlightenment assault on reason prefigured and brought to fruition preeminently in Kant’s philosophy. Unlike those who take Kant to be a defender and advocate of reason, Hicks maintains that, according to Kant, “Reality . . . is forever closed off to reason, and reason is limited to awareness and understanding of its own subjective products” (28). Moreover, Kant was convinced that “the failures of empiricism and rationalism had shown that objectivity is impossible” (30). But this means that, on Kantian grounds, “science is cut off from reality itself” (36). From Kant, then, we learn that “the mind is not a response mechanism but a constitutive mechanism”; that “the mind—and not reality—sets the terms for knowledge”; and that “reality conforms to reason, and not vice versa” (39).

In the history of philosophy, Kant marks a fundamental shift from objectivity as the standard to subjectivity as the standard. . . . With Kant, then, external reality thus drops almost totally out of the picture, and we are trapped inescapably in subjectivity . . . (39, 41).

“After Kant,” Hicks writes, “the story of philosophy is the story of German philosophy” (42). The gap opened up by Kant between subject and object, reason and reality, was not to be closed but rather “set the stage for the reign of speculative metaphysics and epistemological irrationalism in the nineteenth century” from Hegel to Nietzsche (44). With Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger come the formative influences of such Continental postmodernists as Foucault and Derrida, thinkers who gave expression to irrationalism in the twentieth century: “an agreement with Kant that reason is impotent to know reality; an agreement with Hegel that reality is deeply conflictual and/or absurd; a conclusion that reason is therefore trumped by claims based on feeling, instinct, or leaps of faith; and that the non-rational and the irrational yield deep truths about reality” (57).

Hicks’s view that Kant is the decisive forerunner of postmodernism’s anti-realist, anti-reason posture may come as something of a surprise to those who see Kant not as initiating “the reign of . . . epistemological irrationalism in the nineteenth century” (44), but rather as one who punctured the pretensions of the “pure” use of reason if only to emphasize the possibility of a universally valid rational method in philosophy. Moreover, it is a matter of some dispute whether Hicks is correct in his account of Kant’s religious motivation. He writes that Kant was so alarmed by “the beating that religion had taken at the hands of the Enlightenment thinkers” that he resolved to put reason “in its proper, subordinate, place” (29). It is also open to dispute whether Kant was a kind of Kierkegaardian fideist, as he sometimes appears to be in these pages. Nevertheless, Hicks is clearly justified in calling into question Kant’s notion of noumenal reality—an idea as decisive for Kant’s philosophy as it is dubious. But I shall not take up these vexed questions of Kant exegesis and interpretation because even if Hicks were mistaken here, his account accurately reflects how Kant’s ideas have been taken by a great many thinkers, and that is what is central to his purpose. For he means to sketch the historical background of philosophical and political ideas that yielded up postmodernism, and the answer to that question is presumably independent of the question whether everything in that background is itself false.

Here the curtain falls on what might be called Act One of Hicks’s production, with Heidegger busily repudiating logic and reason, all the better to exalt emotion and feelings; with Foucault “reducing knowledge to an expression of social power”; with Derrida turning language via deconstruction into “a vehicle of aesthetic play”; and with Rorty gleefully chronicling the epistemological and metaphysical failures of the realist and objectivist tradition (81).

IV. Postmodernist Politics and the Left

Act Two (chapters four, five, and six) connects epistemology to politics, skepticism to socialism. Hicks observes that “Postmodernists are monolithically Left-wing in their politics” (84), and moreover that those habits of reason, civility, tolerance, and fair play, so characteristic of “the modernist package of principles,” have been “least practiced and even denounced” among the far Left—“particularly among those postmodernists most involved with the practical applications of post-modernist ideas or with putting postmodernist ideas into actual practice in their classrooms and in faculty meetings . . .” (85). Given the absence of “a roughly random distribution of commitments across the political spectrum,” it would seem that epistemology alone is not sufficient to explain postmodernism.

Enter postmodern politics. In a lengthy chapter on “the climate of collectivism,” Hicks argues that four of socialism’s major claims—that capitalism is exploitative; that socialism, by contrast is humane and peaceful; that capitalism is less productive than socialism; and that socialist economies will usher in a new era of prosperity—have been refuted both in theory and in practice, throwing Left-socialist intellectuals into crisis (86-88). Hicks provides helpful discussions of Rousseau’s collectivism and statism, Kant on collectivism and war, Herder on multicultural relativism, Fichte on education as socialization, Hegel on state-worship, and the rise of National Socialism. The upshot of these developments is that “the National Socialists and the collectivist Right were wiped out physically and discredited morally and intellectually. The new battle lines were simplified and starkly clear: liberal capitalism versus Left socialism” (134) The stage is thus set for Hicks’s discussion of Marx and the New Left, which picks up the threads of anti-reason, non-rational commitment, impatience, demoralization, rage, and calls for revolutionary violence (135-170).

The rise of Left terrorism in nations other than those controlled by explicitly Marxist governments was a striking feature of the 1960’s and early 1970’s. Combined with the broader turn of the Left to non-rationalism, irrationalism, and physical activism, the terrorist movement made that era the most confrontational and bloody in the history of the Left socialist movements of those nations.

But the liberal capitalists were not entirely soft and complacent, and by the mid-1970’s their police and military forces had defeated the terrorists, killing some, imprisoning many, driving others underground more or less permanently (170).

With the collapse of the New Left and the socialist movement generally, four figures in the postmodernist movement came into prominence: Foucault, Lyotard, Derrida, Rorty.

All four of these postmodernists were born within a seven-year span. All were well trained in philosophy at the best schools. All entered their academic careers in the 1950’s. All were strongly committed to Left politics. All were well aware of the history of socialist theory and practice. All lived through the crises of socialism of the 1950’s and 1960’s. And come the end of the 1960’s and early 1970’s, all four had high standing in the professional academic disciplines and high standing among the intellectual Left (172).

Accordingly, it was these four academic foes of capitalism, whose tactics and weapons were not those of the politician, activist, revolutionary, or terrorist, “who signaled the new direction for the academic Left” (172).

In order to explain the connection between postmodernist epistemology and politics, it will be helpful to depart from Hicks’s narrative long enough to matte in some context for postmodernist academic ideology and to illustrate this here and in the next section, adding a few examples of my own. Radical political trends in academic philosophy which emerged in the1960’s and 70’s did not simply wither away but gathered force and continue to have dramatic practical effects that are still very much in evidence on campuses across the country. Thomas Kuhn’s insistence on the subjectivity of scientific paradigms, Feyerabend’s epistemological anarchism (“anything goes”) and Rorty’s “philosophy as conversation” became rallying cries for a full-dress relativism. At the same time, colleges and universities began a regime of race and gender preferences in admissions and hiring under the guise of “diversity” and “representativeness”—an evasive rhetoric designed to cloak the diminished importance of intellectual mastery of a subject. Faculty hiring decisions became increasingly constrained by statistical grids. Goals and timetables (if not de facto quotas) became an indispensable part of the selection process, and a cadre of compliance officers swelled the administrative ranks as the great experiment became entrenched.

The problem is that once the university embraced the relativism of political radicalism and the distributive criteria of affirmative action, it was forced to accept the idea that everything is permitted. The distinction between argument and propaganda, between carefully marshaled evidence and inflammatory posturing was contested and finally abandoned. Now anything was intellectually respectable as long as it was “conversation”—and what could not be construed as conversation?—allowing all comers a place at the table or in the seminar room. Of course, far from welcoming all views, the academic Left had an agenda of intellectual and political orthodoxy as rigid and authoritarian as the “canon” of the white heterosexual male hegemony it so despised. One of the most inventive sections of the second half of Hicks’s book is his discussion of the “Kierkegaardian,” “Reverse Thrasymachean,” “Machiavellian,” and “Ressentiment” strategies postmodernist thinkers use to connect their relativistic epistemology and dogmatic political commitments. The first develops sophisticated epistemological strategies for attacking the reason and logic which led to problems with the socialist vision of society (180). The second involves marshaling subjectivist and relativist arguments to support the postmodernist claim that justice is the interest of the weaker and historically-oppressed groups (183). The third uses relativistic epistemology as a rationalization or rhetorical political strategy to throw opponents off-track (186). I discuss the fourth strategy, “ressentiment” postmodernism, in section V below.

As the pendulum swung to the Left, the intellectual and cultural life of the university became destabilized. Hicks does a good job of exposing the irony of those who (as I would put it) insisted that you were not to disassociate yourself from those to whom you felt no particular sympathy, but who also insisted that you must disassociate yourself from those who offended their sensitivities—the “dominant powers,” which meant the usual suspects: the Department of Defense, the “oppressor state” of Israel, the business community, the wealthy, recruiters associated with the military and the intelligence community, conservative think tanks, and anyone else who went against the grain of Left political engagement. Sometimes these strictures took on a vaguely comic aspect. The author of a text I once assigned for an undergraduate course in philosophy of mind insisted on putting ‘they’ and ‘their’ in place of singular impersonal pronouns because he regarded the use of the masculine pronoun in impersonal contexts as “pernicious.” Accordingly, he adopted the plural pronoun throughout his text even when strict grammar required a singular. The habit of thought, you see, comes to be as automatic as that, with no concern for the sweeping generalization, as if all uses of the masculine pronoun in impersonal contexts were injurious and the simple expedient of alternating ‘he’ and ‘his’ with ‘she’ and ‘hers’ was not available.

More often, however, the antagonisms were of vastly greater consequence, and the second half of Hicks’s book, which deals with postmodern political and educational strategies, amplifies and illustrates his second hypothesis about postmodernism:

Postmodernism is the academic far Left’s epistemological strategy for responding to the failures of socialism in theory and in practice (89, emphasis in text).

Why, then, has the Left—and, I should add, not just “a leading segment of the political Left,” as Hicks puts it, but much of the intellectual and cultural Left generally—“adopted skeptical and relativist epistemological strategies?” (174). Hicks’s answer is that if “postmodernism is born of the marriage of Left politics and skeptical epistemology,” we should not be surprised to find that “confronted by the continued flourishing of capitalism and the continued poverty and brutality of socialism,” Left thinkers of the 1950’s and 60’s would “stick to their ideals and attack the whole idea that evidence and logic matter” (90).

V. Academic Noir: Postmodernist Nihilism

In a stunning final section, Hicks concedes that his explanations of postmodernism’s relativism and subjectivism, its Left politics, and the connection between them, do not come to grips with “a psychologically darker streak” running through postmodernism. This requires an explanation that goes beyond treating postmodernism as “a response to skepticism, a faith-response to the crisis of a political vision, or as an unscrupulous political strategy” (191).

The situation is best illustrated in the context of recent academic controversy. As the opportunities to hire new faculty waxed and waned, the university became the main repository of postmodernist influence, and the alienated and disaffected, the irresponsible and preposterous, came and went, affecting the thought and practice even of those who would not normally be characterized as postmodernists themselves.

Consider some inconsistencies: most academics believe, or would say they believe, the theory of evolution, for by their own account they are scientifically up-to-date. (Many are, for good measure, resolutely irreligious.) But they distance themselves from the theory of evolution when what is at issue is whether there is a biological basis for attitudinal or behavioral differences between men and women, as Lawrence Summers learned to his dismay. More tellingly, many in the academy believe the mass of people are prone to false consciousness, rationalization, wishful thinking, and other cognitive disabilities that badly distort their politics and their capacity for free choice in the marketplace, even as they repudiate the very notions of truth and objectivity. A third case: despite paying lip-service to equality and diversity, many Leftists think nothing of invoking cultural stereotypes to denigrate white Southern males generally, whom they call “rednecks” and cowboys.” Of course, the same people are censorious when others fail to uphold the requisite gender, race, class, and sexual-disposition sensitivities. Hicks provides additional examples of this pattern of inconsistency: “all cultures are equally deserving of respect, but Western culture is uniquely destructive and bad”; “values are subjective, but sexism and racism are evil”; “technology is destructive and bad, and it is unfair that some have more technology than others” (184). Hicks also supplies examples of contradictions between postmodernist theory and historical fact: “the West is deeply racist”—but the West ended slavery and only in places where Western ideas are on the ascendancy are racist ideas in decline; “the West is deeply sexist”—but women in the West were the first to get suffrage, contractual rights, and opportunities that most women in the rest of the world utterly lack; “Western capitalist countries are cruel to their poor”—but the poor in the West are far better off than the poor anywhere else in the world (185).

How are we to explain the postmodernist oscillation between subjective relativism and dogmatic absolutism illustrated in these inconsistencies (not to mention the contradictions between postmodernist theory and fact)? As Hicks asks, is the relativism primary and the absolutist politics secondary? Are the absolutist politics primary, advanced by the rhetoric of relativism? In the end, Hicks suggests that “both the relativism and the absolutism coexist in postmodernism, but the contradictions between them simply do not matter psychologically to those who hold them . . . because for them ultimately nothing matters” (186, 192, emphasis in original).

Nihilism, never refuted but subdued for so long that it was not thought necessary to take it seriously, has returned with a vengeance and now has its defenders even among—especially among—academics. Hicks brings Act Two to a striking climax with an apocalyptic revelation: postmodernism is a nihilism.

Hicks supports this thesis with verve and imagination, quoting postmodernists to convict them out of their own mouths. In a fitting irony, he uses the nihilists’ own Saint Nietzsche against them, applying Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment as a diagnostic tool for explaining postmodernist strategies. Nietzsche, of course, used ressentiment in his account of master and slave morality. It is worth quoting Hicks at length:

Slave morality is the morality of the weak . . . Weaklings are chronically passive, mostly because they are afraid of the strong. As a result, they cannot get what they want out of life. They become envious of the strong, and they also secretly start to hate themselves for being so cowardly and weak. But no one can live thinking he or she is hateful. And so the weak invent a rationalization—a rationalization that tells them they are the good and the moral because they are weak, humble, and passive. . . . And, of course, the opposites of those things are evil—aggressiveness is evil, and so is pride, and so is independence, and so is being physically and materially successful (193).

In our time, “Socialism is the historical loser,” and socialists “will hate that fact, they will hate the winners for having won, and they will hate themselves for having picked the losing side. Hate as a chronic condition leads to the urge to destroy” (194). But they will not limit their rage to political failure:

Postmodern thinkers hold that not just politics has failed—everything has failed. Being, as Hegel and Heidegger taught us, really has come to nothing. Postmodernism, then, in its most extreme forms, is about driving that point home and making nothing reign (194).

Hicks makes it clear that Leftist acrimony is a deeply burnished feature of the postmodernist armory. “In the modern world,” he writes, “Left-wing thought has been one of the breeding grounds for destruction and nihilism” (192). Its rage is barely concealed—aesthetically as well as politically, which is why when Hicks comes to central themes in twentieth century art, he writes (alluding to the motto of the Dada movement, “Art is shit”) that “postmodernism is a generalization on Dada’s nihilism. Not only is art shit, everything is” (197).

The thesis that postmodernism engaged and succumbed to nihilism is illustrated in Hicks’s discussion of Marcel Duchamp’s version of the Mona Lisa, with the cartoonish moustache added by Duchamp, and Robert Rauschenberg, who “took Duchamp a step further. Feeling that he was standing in the shadow of Willem de Kooning’s achievements, he asked for one of de Kooning’s paintings—which he then obliterated and then painted over” (198-199). Hicks says these works made the statements “Here is a magnificent achievement that I cannot hope to equal, so that instead I will deface it and turn it into a joke” and “I cannot be special unless I destroy your achievement first,” respectively (198-199). No wonder deconstruction—the “literary version of Duchamp and Rauschenberg” (199)—is “arrayed primarily against works that do not square with postmodern commitments” (199).

Deconstruction has the effect of leveling all meaning and value. If a text can mean anything, then it means nothing more than anything else—no texts are then great. If a text is a cover for something fraudulent, then doubt about everything apparently great creeps in (199).

Hicks’s analysis at this point has an edgy ingenuity to it, seeing the hostage art gives to nihilism as symptomatic of the twentieth century’s characteristic malaise, with all the postmodernist pathologies it reflects. To be sure, some minor inaccuracies have found their way into his account of Rauschenberg, who completely erased (not painted over) a drawing (not a painting) given to him by de Kooning (who was involved in the project from the start, even if only reluctantly), for the express purpose of determining “whether a drawing could be . . . created by the technique of erasing.” Rauschenberg tells us he spent a month, and forty erasers, trying to do just that. He then framed, dated, and gave the item the title Erased de Kooning Drawing and exhibited the erasure as his own work of art. In this respect, the enterprise may be thought to bear a family resemblance to 4’33”—the notorious piano piece by the composer John Cage, which consists of a pianist sitting at a keyboard for exactly 4 minutes and 33 seconds without playing a note. In both cases it is arguable that we do not have an art work here at all, to say nothing of one which sends a message of nihilism. But perhaps Hicks only means that the antics involved in the process of erasing the de Kooning drawing (or, in the cases of Duchamp and Cage, the act of painting a moustache on the Mona Lisa or sitting at a piano keyboard in silence) together with the chutzpah of putting it forward as an artwork of one’s own, is the vehicle of the nihilistic message.

In any case, I take it Hicks’s remarks in this context are further illustrations of postmodernism’s descent into nihilism:

To the postmodern mind, the cruel lessons of the modern world are that reality is inaccessible, that nothing can be known, that human potential is nothing, and that ethical and political ideals have come to nothing. The psychological response to the loss of everything is anger and despair (198).

So goes Hicks’s diagnosis of postmodernist nihilism’s attack on “the Enlightenment’s sense of its own moral worth”:

Attack it as sexist and racist, intolerantly dogmatic, and cruelly exploitative. Undermine its confidence in its reason, its science and technology. The words do not even have to be true or consistent to do the necessary damage (200).

Of course, as Hicks acknowledges, identifying the roots of postmodernism and linking them to contemporary nihilism does not refute the doctrine. As the curtain comes down on page 201, one waits in vain for Act Three. Hicks knows he has an unfinished agenda “essential to maintaining the forward progress of the Enlightenment vision and shielding it against postmodern strategies,” namely, a refutation of postmodernism’s historical premises as they are found in Rousseau, Kant, and Marx and an articulation and defense of the main alternatives to them (201). Let us hope that Stephen Hicks will apply the historical understanding, analytical insight, and argumentative skills so much in evidence in Explaining Postmodernism to complete the work that remains to be done.

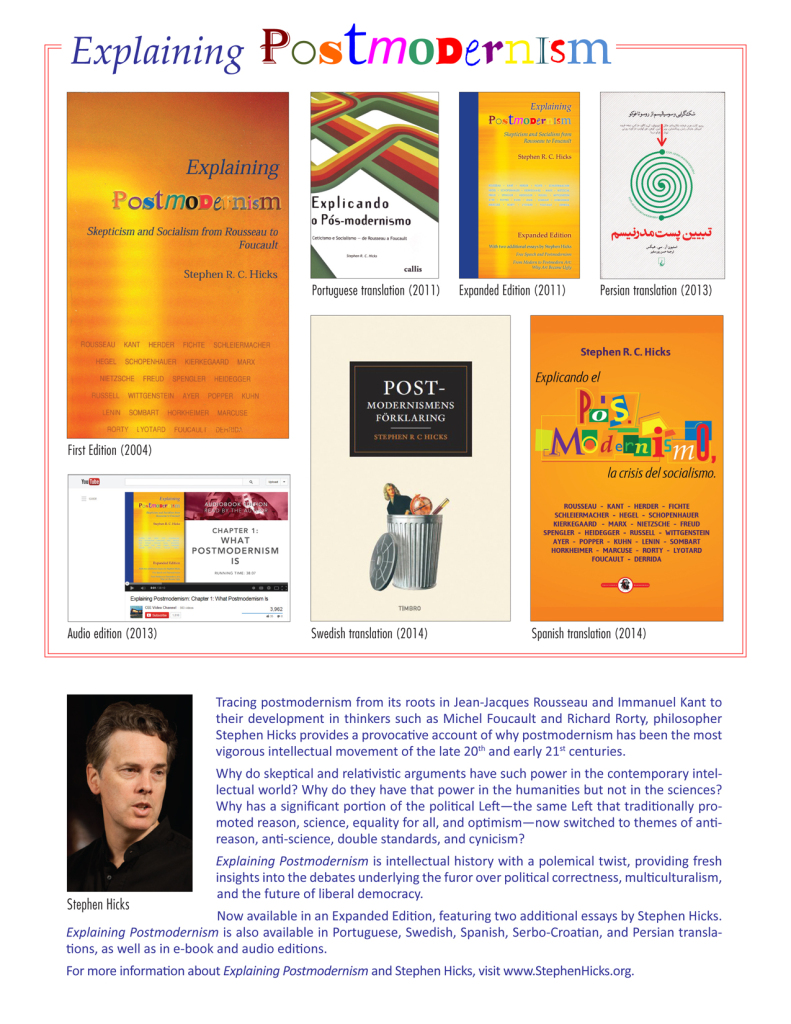

Related: Audiobook version of Explaining Postmodernism. Information about other editions and translations.

Pingback: Flee Corrupt “Authenticity” and Come Into the Light! | theology like a child

The review is thoughtful and thorough…in fact, so thorough that it makes me wonder if reading Explain Postmodernism is necessary. I might anyway…