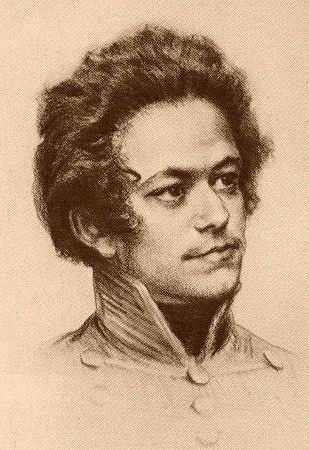

Young Karl Marx, full of Sturm und Drang and apocalyptic fervor, wrote poetry expressing his strongest desires. Two excerpts, the first from Feelings (1836):

“Worlds I would destroy for ever,

Since I can create no world,

Since my call they notice never,

Coursing dumb in magic whirl.”

And the second from The Fiddler (1837):

“I plunge, plunge without fail

My blood-black sword into your soul.

That art God neither wants nor wists,

It leaps to the brain from Hell’s black mists.

Till heart’s bewitched, till senses reel:

With Satan I have struck my deal.”

For an upcoming episode in my Open College podcast series, “Socialism: Scientific or Religious?“, I discuss these excerpts and their significance for understanding Marx as ideologist and violent-revolution aspirant.

Pingback: M*A*S*H units pulled after ZERO Covid patients and much more: Links 1, July 7, 2021 – Vlad Tepes

Stomach turning to compare the output of Marx with the output of a man born around the same time.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Buchanan_Eads

When he was twenty-two, Eads designed a salvage boat and showed the drawings to two shipbuilders, Calvin Case and William Nelson. Although Eads had no previous experience and no capital for the project, Case and Nelson were impressed with him and the three became partners.[4]

At that time, salvaging wrecks from the Mississippi River was nearly impossible because of strong currents.[4] Eads made his initial fortune in salvage by creating a diving bell, using a 40 US gal (33 imp gal; 150 l) wine barrel to retrieve goods sunk in riverboat disasters.[4] He also devised special boats for raising the remains of sunken ships from the river bed. Eads did much of the diving himself because the work was so dangerous. His work gave Eads an intimate knowledge of the river, as he explored its depths from the Gulf of Mexico to Iowa.[4] Because of his detailed knowledge of the Mississippi (the equal of any professional river pilot), his exceptional ability at navigating the most treacherous parts of the river system, and his personal fleet of snag-boats and salvage craft, he was afforded the much prized courtesy title of “Captain” by the rivermen of the Mississippi and was addressed as Captain Eads throughout his life.[6]

In 1861, after the outbreak of the American Civil War, Eads was called to Washington at the prompting of his friend, Attorney General Edward Bates, to consult on the defense of the Mississippi River.[7] Soon afterward, he was contracted to construct the City-class ironclads for the United States Navy, and produced seven such ships within five months:[8] St. Louis, Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, and Pittsburgh.[9] He also converted the river steamer New Era into the ironclad Essex. The river ironclads were a vital element in the highly successful Federal offensive into Tennessee, Kentucky and upper Mississippi (February–June, 1862). Eads corresponded frequently with Navy officers of the Western Flotilla, and used their “combat lessons learned” to improve vessels during post-combat repairs, and incorporate improvements into succeeding generations of gunboats. By the end of the war he would build more than 30 river ironclads.

The last were so hardy that the Navy sent them into service in the Gulf of Mexico, where they supported the successful Federal attack on the Confederate port city of Mobile. All senior officers in the Western Theater, including Grant and Sherman, agreed that Eads and his vessels had been vital to early victory in the West.