Lesson: The groundwork for this generation’s militant “antiracist-but-not-really” wokism was prepared by my generation.

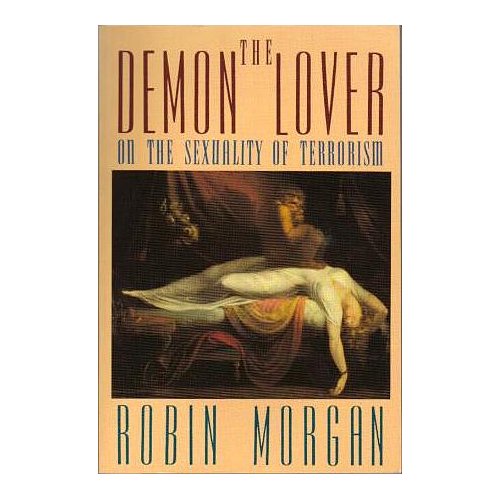

“My white skin disgusts me” was my introduction to Robin Morgan’s autobiographical The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism, published in 1989, recounting her journey through the New Left, Marxism, postmodernism, left feminism, racialism, and flirtations with revolutionary violence. The fuller quotation from Morgan:

“My white skin disgusts me. My passport disgusts me. They are the marks of an insufferable privilege bought at the price of others’ agony. If I could peel myself inside out I would be glad. If I could become part of the oppressed I would be free.”[1]

Morgan’s being white and American are great sins, she felt, but she found some redemption in being female and thus a member of an oppressed group. Men—even the revolutionary men she knew—are part of the patriarchal system that continues to exploit women: “Despite minor variations among some groups studied, urban terrorism remains a predominantly male phenomenon.” (63) So even the New Left needed a major housecleaning of sinfulness: “the new left was terminally diseased with sexism and toxic with characteristic U.S. arrogance and impatience.” (219)

Perhaps eliminating (exterminating) the males is the best solution?

“I haven’t the faintest notion what possible revolutionary role white hetero-sexual men could fulfill, since they are the very embodiment of reactionary-vested-interest-power. But then, I have great difficulty examining what men in general could possibly do about all this. In addition to doing the shitwork that women have been doing for generations, possibly not exist? No, I really don’t mean that. Yes, I really do.” —

Morgan is one of those young people that 1960s New-Left guru Herbert Marcuse thought would save the left-revolutionary movement. by learning to shoot guns, make bombs, become militant. Destruction is a much greater turn-on even than sex, Morgan confesses:

“Sex to this point in my life has been trivial, at best a gesture of tenderness, at worst a chore. I couldn’t understand the furor about it.

“But this [violence and destroying things]—the hands shaking, the throat dry, the heart pounding, the brain in a blur of excitement, the body poised, exhilarated, the risk of being swept into obliteration, the aphrodisiac in demanding power—surely this surpasses whatever they mean by sexual joy.” (pp. 229-230)

Morgan quotes Julio Cortazar: “One had to live in paroxysm the image of liberation … in spite of the inevitable worst options; the revolutionary’s hands had to be stained by bile and excrement, like a surgeon-in order to extract the tumor and give new life to the young man.” (117-118)

So the asexual young women thus flirted with homegrown militant and terrorist groups that fed into the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground. “I was, however, involved in small nameless pre-Weathermen groups that believed in ‘armed propaganda.'” (221) Further: “I was also not the only one convinced that the second American Revolution was imminent, and I was not the only one who vowed to bring that revolution about — by any means necessary.” (218)

She cites the following as formative of her intellectual background:

- “Carlos Marighella, a Brazilian who left the Communist party because of its insufficient militancy, wrote the Handbook of an Urban Guerilla. It became one of the seminal (I use the word intentionally) books of the U.S. New Left and has been called the bible of insurgent forces throughout the Third World.” (73)

- Michel Foucault on deconstructing the family (129).

- Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, which she read in the early 1960s and which inspired her to write an feminist version entitled The Wretched of the Hearth (160).

A poem entitled “Annunciation” that Morgan wrote in 1969:

I am pregnant with murder,

The pains are coming faster now,

and not all your anesthetics

nor even my own screams

can stop them.

The status quo in America that Morgan was fighting had two elements, one religious and one secular. “The philosophical way took the form of fundamentalist religion promulgated with missionary zeal, as in the spread of fundamentalist Islam or Pentecostal Christianity. The secular way took the form of multinational corporations, the one-world government of tomorrow.” (295)

Channeling Rousseau and Kant: “Those trapped inside the closed-system thinking of patriarchy, no matter who scintillant their intelligence, cannot perceive another ‘world of appearances,’ a different kind of company, an alternative collective action, or ways of living (and even dying) than would not be lonely, impotent, or vitalized by violent proximity to death.” (325)

Reacting against Sartre’s eulogizing anti-colonial violence. Sartre had written of violence’s cathartic and manhood-generating powers:

“Make no mistake about it; by this mad fury, by this bitterness and spleen, by [the colonized’s] ever-present desire to kill [-the European], by the permanent tensing of powerful muscles which are afraid to relax, they have become men; … this irrepressible violence is neither sound and fury, nor the resurrection of savage instincts, nor even the effect of resentment; it is man recreating himself, ,, no gentleness can efface the marks of violence; only violence itself can destroy them.” (163)

But, Morgan argues, “the Left did not go far enough, in analysis, vision, or practice.” (219)

Only a new feminism can show the way: “The powers of female sexuality, in all of their expressions and redefinitions (maternal, celibate, bisexual, lesbian, and heterosexual) have the potential of forming completely different relationships in the twenty-first century.” (327)

Thus: The 1960s intellectuals teach many young Robin Morgans, who in turn become cultural leaders in the 1980s and 90s. They teach the next generation who come into their own in the 2010s and 20s — i.e., our generation’s Woke SJWs.

Sources:

[1] Robin Morgan, in a chapter entitled “Longing for Catastrophe,” p. 224 of The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism (N.Y.: Norton & Co., 1989).

Herbert Marcuse, quoted in Chapter 5 of Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault.

Related:

Walter Olson on “The laundering of evil.”

David Thompson in “Little Knots of Agony” deconstructs an angry pomo person of color.