By Stephen R. C. Hicks

The many Scrooges // Robin Hood analogy // Scrooge as villain of Socialism // as anti-Christian // as Savvy Investor // as Environmentalist // as Malthusian // as anti-Commercialization // Scrooge’s Aristotelian hero’s journey

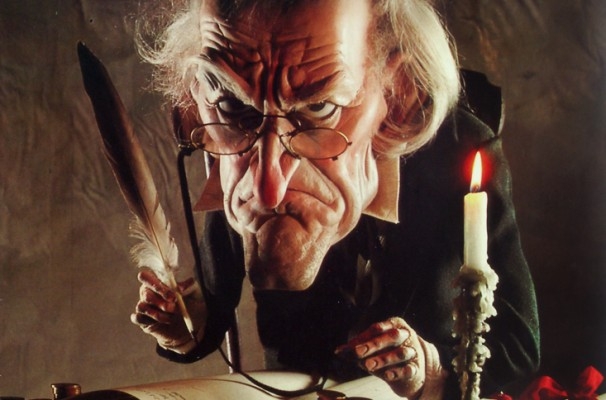

We all know the tale of Ebenezer Scrooge. Or do we?

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol has generated an astonishing variety of interpretations, and as with most rich tales the interpretations often tell us as much about the interpreter as the original story.

The legend of Robin Hood is a good example. Was the outlaw of Sherwood Forest someone who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor? In that interpretation, the rich are bad and undeserving and the poor are good and deserving, so Robin Hood’s compulsory redistribution efforts make him a kind of Christian Socialist. Or was Robin Hood really taking back monies that had been confiscated by an oppressive government of aristocrats and their cronies—and returning them to those who had produced the wealth in the first place? That makes him a proto-capitalist defender of property rights, limited government, and fair taxes. We do not know the real Robin Hood, as the legend’s origins are lost in the mists of medieval times.

With Dickens’s Scrooge, though, we actually have a text to refer to. But that has not stopped a flood of alternative interpretations of the complicated central character.

We have Scrooge the Villain according to Socialism: Think of poor Bob Cratchit. Scrooge the boss could very well sacrifice some profits and pay Cratchit the worker more, but the supply-and-demand system cruelly gives employers the upper hand and drives down wages, leaving exploited employees no option but to accept meager income. Bob Cratchit is thus a poster-boy for exploited employees everywhere.

Or there is Scrooge the anti-Christian. Out of simply charity, Scrooge should feel moved to help those less fortunate than himself—the many beggars in the streets and Cratchit’s rather large family with many mouths to feed, and especially Tiny Tim, whose handicap tugs at our heart. Charity and Mercy should be your business, cried the ghost of Jacob Marley to Ebenezer Scrooge.

And there is Scrooge the Homo Economicus and Savvy Investor. Ebenezer is a friend to the economy by being an extraordinarily effective cost cutter. He allows no unnecessary expenses at the office or at home—and every penny he saves is re-invested in new enterprises. Scrooge is tops at choosing investments that will be profitable, thus efficiently allocating resources, creating jobs, and thereby growing the economy.

There is also Scrooge the Environmentalist Hero. Scrooge uses hardly any candles or coal, either for cooking or for heating his home and office—he kept “a very small fire,” Dickens tells us—and he wears his clothes until threadbare. Scrooge thus sacrifices personal comforts and in doing so preserves the Earth’s resources. Normally we think of the selfish as those who indulge themselves at the expense of others. But Scrooge denies himself, thus leaving those resources for others to consume. How selfless. We should thank him for doing his bit to combat global warming and conserving landfill space.

Closely related is Scrooge the Malthusian fighting the Scourge of Overpopulation. Scrooge tells us that he already pays support for the workhouses and the Poor Law to help those who are badly off. Beyond that, however, he draws a line, pointing out that the nation’s population is already beyond its capacity and good public policy must “decrease the surplus population.”

Then there’s Ebenezer Scrooge, hero of the Anti-Over-Commercialized-Christmas crowd. Just you try cutting back on the number of presents you buy for your children and others—and see how much emotional grief and blackmail you will get. But Billy’s getting a new Gamebox! And Robert is buying a car for his wife! The advertisers and the Joneses all expect us to keep up. But Scrooge, admirably, has the intestinal fortitude to overcome such pressures. We all need more Bah! Humbug! in our souls to resist selling out to commercialism.

All of the interpretations have a textual grain of truth, though they all have the defect of taking one element of Scrooge and, in isolation from the rest, stressing it to its limit.

So let me pick and choose from the above and add a few more elements to give you my take on the appealing transformation of Ebenezer: I give you the Scrooge the Aristotelian.

Before his change, Scrooge is hardly a happy man. Miser and miserable keep close company. He undoubtedly gets some pleasure for making good business decisions and having a positive bottom line in his ledgers. But beyond that, in the rest of his life he is impoverished, both physically and psychologically. He does not enjoy the company of Bob Cratchit, the person with whom he spends more time than anyone else. He is estranged from his family and has no friends. He does not enjoy travel and the arts. He does not enjoy tasty food or drink, and in the winter he is cold.

That is to say, Scrooge has closed himself off to the vast majority of the things that make human life worth living. He has allowed one genuine value—making money—turn into an obsession. His mistake is not only that he devotes himself to that one pursuit to the exclusion of other valuable human pursuits; it is that he does not allow himself fully to enjoy the rewards that successful money-making can bring.

And this is what he comes to realize when the ghosts enable him to see the true opportunity costs—past, present, and future—of the choices he has made.

When the final ghost has released him and Scrooge awakens to a new day, he becomes a philosopher. He realizes that he is alive and that life is for the living—in a fully human way.

He should take pride in his accomplishments in business and the rewards they bring. He should enjoy the friendship of those he spends time with at work and realize that their success and his are deeply interrelated. He should know that family connections can run rich and deep and reward us with a steady love. He should know that life is a matter of investment and reinvestment in all areas—business, friendship, family, food, drink, and culture—and that the greatest satisfactions come to those who invest themselves most liberally. He should know that the fact that millions of his fellow human beings are embarked upon the same great project of life, and that it is glorious to have a day set aside to celebrate that fact.

To speak of pride, friendship, liberality, and an overarching wisdom about how they all contribute to a fully self-realized life—all of that is to make Dickens’s Scrooge sound like a Victorian-era reading of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. The classic status enjoyed by A Christmas Carol may be due to the combination of Charles Dicken’s story-telling brilliance and the timeless truths expressed by the wisest of all Greeks.

We can go one step further. At the end of A Christmas Carol, Dickens has Scrooge be aware that his life-change has been profound—and that many people have mocked him for it. But Scrooge puts their mockery in proper context: It is never too late to change for the better. It is always the right time to strive for what is truly best in life. And having the courage to make those commitments—that is what makes possible the strongest self-satisfaction with one’s life:

“His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him.”

* * *

Related: An audio version is available in my Open College with Stephen Hicks series, at my website, YouTube, Bitchute, Apple Podcasts, SoundCloud.