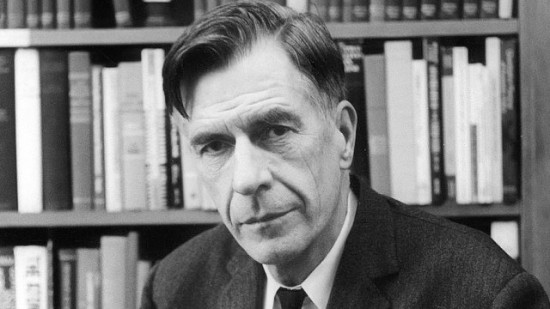

In the mid-20th century intellectual world, JKG was widely regarded as an original and insightful thinker on economics and politics. He was professor at Harvard and author of widely read books such as The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State. While I was a university student in Canada (coincidentally, Galbraith and I both graduated from the University of Guelph), I recall finding those titles on my parents’ bookshelves and reading them.

He never struck me positively — my impression was of a cranky gadfly using his intelligence to poke cleverly here and there — though I reserved judgment as I was young and did not have the expertise or experience to form a final judgment. Yet I did frequently use Galbraith’s “The Dependence Effect” article in my Business Ethics classes over the following years, and this paragraph from it has always stuck with me. It is his scornful summary of life in America in the middle of the 20th century:

“The family which takes its mauve and cerise, air-conditioned, power-steered, and power-braked car out for a tour passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards, and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground. They pass on into a countryside that has been rendered largely invisible by commercial art. (The goods which the latter advertise have an absolute priority in our value system. Such aesthetic considerations as a view of the countryside accordingly come second. On such matters we are consistent.) They picnic on exquisitely packaged food from a portable icebox by a polluted stream and go on to spend the night at a park which is a menace to public health and morals. Just before dozing off on an air-mattress, beneath a nylon tent, amid the stench of decaying refuse, they may reflect vaguely on the curious unevenness of their blessings. Is this, indeed, the American genius?”

To which I juxtapose immediately Galbraith’s admiring assessment of Maoist China’s economy, written after an investigatory trip to the land of the Cultural Revolution:

“There can now be no serious doubt that China is devising a highly effective economic system.” It is “more flexible, practical and dynamic and with a strikingly more successful protection of quality”. “That the Chinese have a genius for organization has been the revelation of an infinity of scholars.” Not everything is perfect and not all the details are clear yet, but, for example, “Greater Shanghai, with a population of around 12 million, has 424 hospitals with 44,000 beds and about 11,500 doctors, and thus arguably a better medical service than New York. The average quality of practice is almost certainly higher in New York.” And so on.

Note that the word “genius” appears in both passages — used sarcastically to describe American society and gushingly to describe Chinese society.

The upshot: Galbraith is yet another in a long, sorry line of left-leaning intellectuals — the fellow-travelers who went to Soviet Russia, China, Cuba — who could not help but admire what obviously were (and documentably turned out to be) brutal and impoverishing dictatorships — and who could not help but disdain and even be oblivious to the actual accomplishments of the capitalist democracies. Like the rest, he occasionally adopted the pose of the steely eyed, hard-nosed, centrist pragmatist, yet the normative wish for hard-left role models to worship is magnetic for him. Ideological blinders, indeed.

Sources: John Kenneth Galbraith, “The Dependence Effect.” In Hoffman & Moore, Business Ethics, p. 331. John Kenneth Galbraith, “Galbraith has seen China’s future—and it works,” The New York Times. Thanks to David Boaz for the NYT link.

Related: “The Crisis of Socialism,” Chapter 5 of Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault.

Stephen, methinks you short-change Galbraith. This is truth to be found beyond Ayn Rand.

https://academic.oup.com/book/3825

Hmmm … your second sentence is trivially obvious, and your first sentence is a just a claim.

In your own words, can you state what’s enduring in Galbraith, and/or not just political ideology looking for economic-theory support?