Anton Chekhov is a great writer, in large part because he follows ruthlessly a principle of selectivity named after him: “Chekhov’s gun” is principle of writing that says that every element in a narrative must be essential and irreplaceable, and anything that is neither must be eliminated.

But I don’t like reading Chekhov. I read Three Sisters in a theatre course in college and remember respecting the directness of the writing but not the story. At the time I read a few other short stories and had the same impression. Since then I have never returned to Chekhov for pleasure.

I was reminded why by the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose describes some of his music as inspired by Chekhovian themes:

“I remember that once I accidentally came across Chekhov’s thoughts on how the Russian man only lives a real life until he’s thirty. We rush when we’re young, we think everything is ahead, we hurry, pouncing on everything. We fill our soul with whatever comes our way. But after thirty our soul is filled with gray rubbish. That’s amazingly true.”[1]

And this: “Chekhov also said that Russia is a land of greedy and lazy people who eat and drink prodigious amounts and like to sleep during the day and snore while they sleep. People marry in Russia to keep order in the house, and take mistresses for social prestige. Russians have the mentality of a dog — when they’re beaten, they whimper softly and hide in the corner, and when they’re scratched behind the ear, they roll over.”[2]

Chekhov may or may not be a good journalist or sociologist of the Russian character. I don’t know. But these are assertions by an artist. And I am sure, as Chekhov was sure, that there are at least some Russians whose lives after thirty are vital and colorful, and that some Russians fight for their principles, eat healthily, and marry for love.

But in his writings Chekhov chooses not to focus on them. Instead, as in Three Sisters, he writes of a spinster who never found love, a cuckold, the bad-tempered woman who cuckolded him, a man with a low-end job and hopeless debts stuck raising a child, and so on.

An artist’s decision consistently to focus on the disappointments, failures, and betrayals in life — when he knows that satisfaction, success, and loyalty are possible — where does that choice come from?

It is a choice: The artist is free to do whatever he wants in his writings. The artist is a god — in his work, an artist decides who lives and who dies, who is successful and who fails, what goals his characters adopt or avoid, and so on. Those choices have to come from the artist’s judgment about what is most importantly true.

As consumers of art, our responses are also about importance. We don’t read 19th-century Russian literature primarily to learn about 19th-century Russia — history books and old newspapers can give us that. Instead, we read literature that uses, say, 19th-century Russia as a vehicle for experiencing important truths about the human condition. If the author’s assessment of the human condition affirms your own, you respond positively to the experience — you feel intellectual and emotional affirmation. If not, you feel alienation; the work may contain elements of interest, but the overall effect will be neutral or negative.

Sources: [1] Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich, as related to and edited by Solomon Volkov. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Harper and Row, 1979, p. 180. [2] Ibid., p. 179.

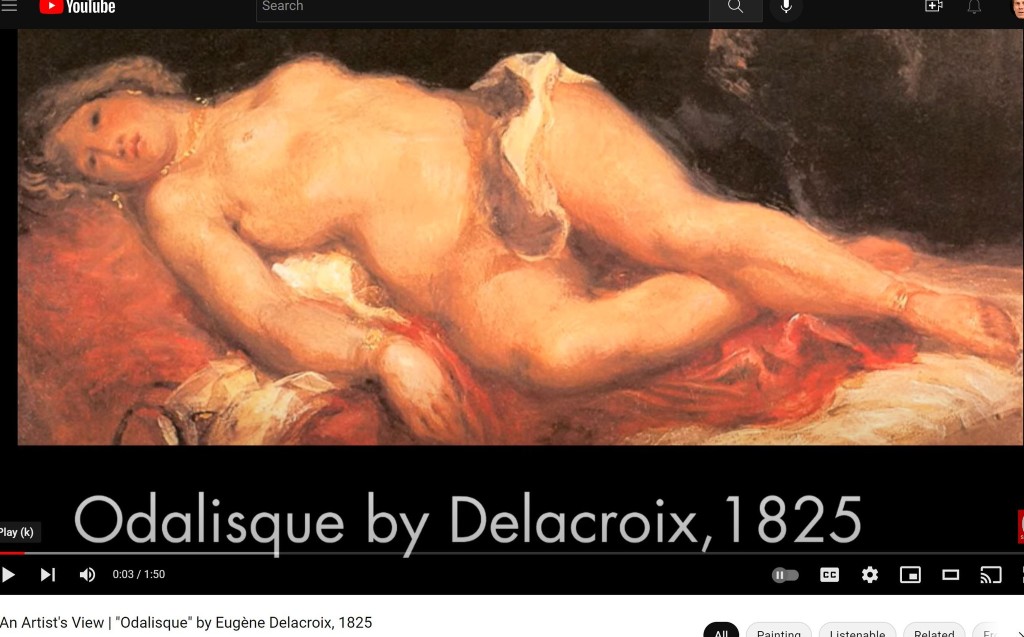

Related: Newberry short commentaries on the great works in art history:

“But after thirty our soul is filled with gray rubbish.” What a sad self-revelation.

On another note, Ayn Rand said something like, “A culture may be judged by the art it applauds.” The picture of Russia is quite consistent with Dostoyevski’s, Gorki’s, and to some degree, Tolstoy’s. Writers must have an historical sense.

One might also consider that only in Russia, essentially a “backward” country (and, in China, completely “gone”) did Marxism and Leninism take root. Rand also deplored (in a Phil Donahue talk) Russia’s obsessive religiosity, so, take away the Russian Church, and you have a residual, moronic devotion to Marxism. However, evaluating Russian spirituality is another matter. They are devoted to the “human virtues.” To the family, something like the Irish, who share their enthusiasm for revolution. Alas, the steppes of Russia have always needed a heavy hand. Only Gogol seems to explore their pleasant side. One also does well to read Vladimir Nabokov on the subject. A great people who produce geniuses like Pushkin, Tschaikovski, Rimsky, Mussorgski, and that ultimate political monster, Josef Stalin.

Nicely put, Dr. Hicks.

Lovely article. I agree complete. We are making a series of stories, as playlist for our channel. I completed one called –Bet.

It illustrates your point too well. Sick story.

Yes, he writes well. But chooses the worst.