Do We Know What We Advocate? Stephen Hicks’s Defence of Individualism

By Professor Piotr Kostyło

Piotr Kostyło is Head of the Department of Philosophy of Education at Kasimir the Great University in Bydgoszcz, Poland.

The forty-five years of communism in Poland (1944-1989) were marked by the government reminding society of the atrocities committed during World War II by the Nazis. The patriotic attitudes of citizens were formed on the basis of overt hostility to the Germans, who were not only held responsible for Nazi war crimes, but also presented as a source of constant military threat. As Poles, we were told, we had to defend ourselves against this threat, against a new war. And since we were too weak to defend ourselves, we had to ask the great Soviet people for help. In this way, the Communists justified the presence of Soviet troops on Polish territory and, more broadly, the total political and economic subordination of Poland to the interests of the Soviet Union. The Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks and the Baltic nations heard analogous justifications. The arguments were thoroughly cynical, since democratizing Germany was not a threat to anyone at the time, and no central European nation ever asked the Soviet Union for any help of this kind. Frightening central European societies after 1945 with allegedly resurgent Nazism in Germany was one of the key tools to keep them in a state of bondage and submission to the Soviet Union. The order which was formed after the Second World War in Europe and beyond was also a result of the disaster caused in the 1930s by the Nazis. The end of the Second World War in 1945, which from the perspective of citizens of the United States and Western Europe meant an end to totalitarianism and a return to the idea of freedom, was interpreted differently by the majority of citizens in Central and Eastern Europe. For them, the end of the war meant the replacement of one oppressor, Nazism, by another, communism. I am writing these words in the introduction to this text in order to emphasize the complexity of the issues that I am going to deal with below. The madness of enemies of freedom does not end with their death, but it lasts in time and affects future generations of peoples and nations, whose only crime was that they found themselves on the path of this madness.

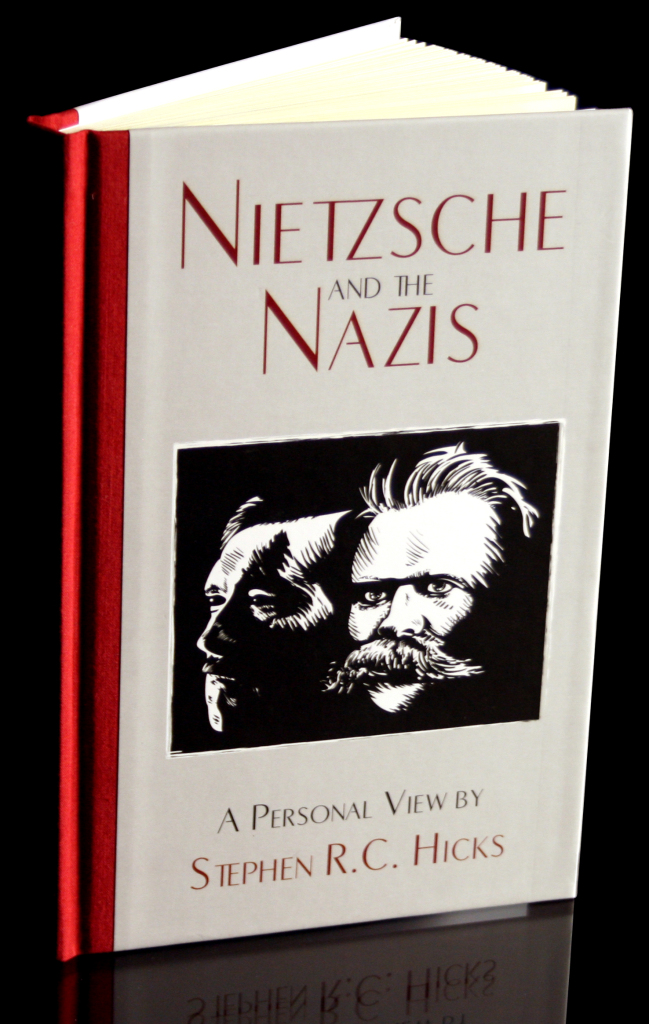

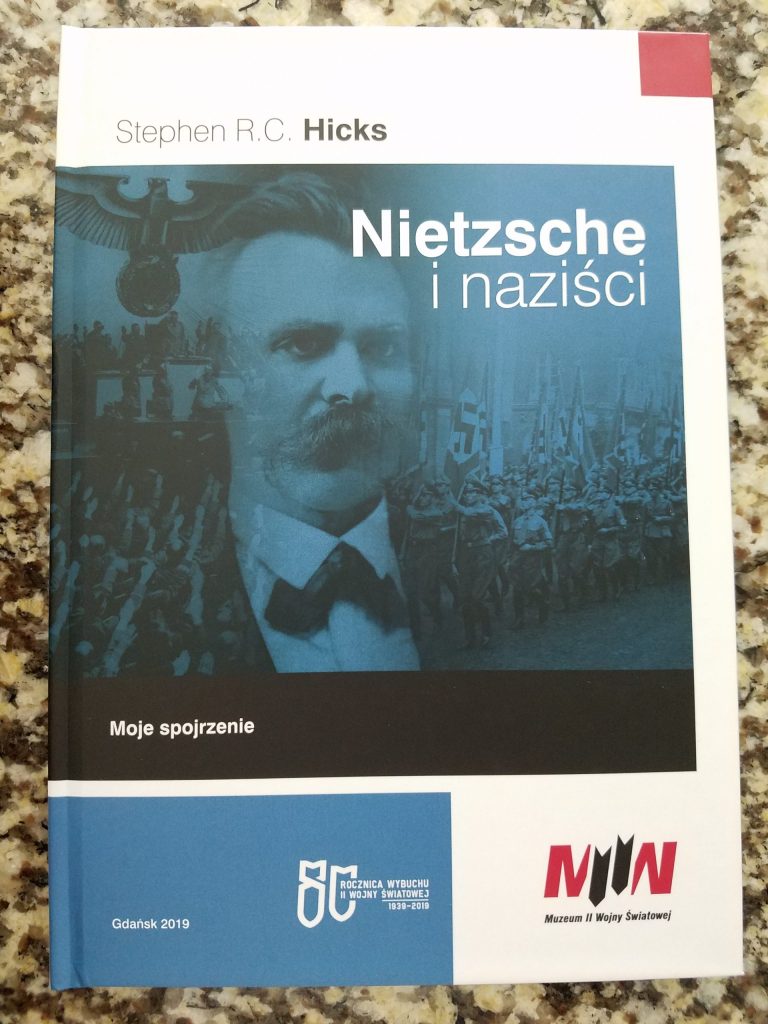

The reference point for my analysis is the book by Stephen Hicks, Nietzsche and the Nazis. A Personal View. It was published in Polish on the initiative of Mr. Przemysław Zientkowski by Martin Fuhrmann Chojnice Foundation in 2014. Hicks is an American philosopher specializing in ethical and educational issues, currently employed at the Rockford University, Illinois. Owing to translations of his books, he is a scholar recognized in many European countries, as well as in both Americas. He promotes his ideas also by running an interesting blog https://www.stephenhicks.org/. The book Nietzsche and the Nazis. A Personal View was published in the USA in 2010, and a two-hour documentary on this subject recorded with the author’s participation in 2006, and then distributed on DVD, became the basis for the development of the text. Thus, the publication of the book in Poland should be greeted with great satisfaction. It raises important issues, often cited in the philosophical debate in our country, presenting at the same time the American perspective, so different from ours.[1]

The book consists of nine parts, in which the author presents the various aspects of the relationship between National Socialism and Nietzsche. The message of the book, however, is much broader. It shows the interdependencies between political systems together with the ideologies underlying them and the great philosophical systems inspiring human minds and hearts over the centuries. The adoption of a particular system by governing forces is not without influence on their political agenda. Moreover, Hicks even claims that the impact of philosophy is of key importance here, even more important than the impact of other elements of culture such as the economy, education, religion and law. Thus, governing authorities and citizens are always in favour of something, they identify with some ideas, and sometimes even set the ideals they want to pursue. It is important for us to know what exactly our leaders advocate and what we ourselves want to be in favour of.

In the next part of the text I shall deal with three issues.

The first one concerns the question that has attracted the attention of many prominent thinkers, as well as reflective ordinary people since the end of World War II, namely, how it was possible that the German people, who gave the world so many distinguished creators of culture, and was for centuries admired by the civilized world, including many Americans, could perpetrate with the hands of their leaders and their supporters such terrible crimes. “How could Nazism happen?” asks Hicks on p. 5 of his book. After all, the German nation was the most educated in Europe, gave the world many outstanding scientists, including Nobel Prize winners (some of whom, Hicks reminds us, actively supported the Nazis). Rich literature on the subject suggests different answers; the author presents a concise overview of them on pp. 6-7. However, he rejects these answers, calling them “little convincing”. Instead, he proposes his own explanation, which he calls “philosophical”. I shall return to this later in this text.

The second issue is the title question of the impact of Nietzsche’s philosophy on the developers of National Socialism and the programme of their political and social action. The question of Nietzsche’s responsibility for fascism, and especially for the Holocaust, is one of the most frequently asked by authors dealing with the great German philosopher. To what extent did this uncompromising critic of bourgeois society at the end of the 19th century contribute to the formation of the ideological foundations of National Socialism? Can he be held co-responsible for spreading the hatred of the Jews in the 1920s and 1930s, and then for their extermination? How did the main ideologists of German fascism, with Adolf Hitler at the head, treat Nietzsche and his philosophy? It is these, and many other questions, that the author answers in a substantial part of his book. I shall also return to them in the further part of my argumentation.

And, lastly, the third issue, which is related to the cultural situation in which our country and other countries of Central and Eastern Europe found themselves after the fall of communism. Like fascism, communism was a criminal ideology; it led to the death of more people than the system created by Hitler. In communism, too, many prominent intellectuals unconditionally supported the political system and its ideology. It is not about asking them now to account for their earlier choices, or even asking, following the author, what attracted these people to a totalitarian vision of the world (after all, numerous, in-depth studies have been written on the subject, the most famous of them being The Main Currents of Marxism by Leszek Kołakowski). Hicks’s book, and especially its ending, brings us to the question: what next? Having rejected communism, we must choose such a socio-political system that will protect us to the highest degree against the return of totalitarianism. I shall address this in more detail in the last part of this text.

Let us start then with the question posed by Hicks: how could this happen? German fascism was able to occur and then achieve such great success, says the author, because it appealed to very noble motives in the minds of the Germans, especially young people. It was not an ideology which encouraged evil, announced atrocity, or declared human degradation. On the contrary,

“Nazi intellectuals and their followers thought of themselves as idealists and as crusaders for a noble cause. This may be even harder to accept. The National Socialists in the 1920s were passionate men and women who thought that the world was in a crisis and that a moral revolution was called for. They believed their ideas to be true, beautiful, noble, and the only hope for the world.” (Hicks, 2014, p. 11).

Hicks rightly notes that the Nazis invoked not so much ideas, but ideals; they did not want to join existing projects, but to implement a project which no one had managed to achieve yet. This gave impetus to their actions and provided them with energy, owing to which, step by step, they conquered the minds of fellow citizens and gained real power. Ideas that exist in the world certainly do have a great impact on us, but it is ideals that inflame the heart and induce us to take extraordinary actions. Their importance in the lives of individuals and communities had been emphasized before Hicks by another American philosopher, William James. He wrote about this in, among others, What Makes a Life Significant?, stressing that what appeals most strongly to the consciousness of people is the heroic struggle with the adversity of fate, in the name of high ideals. “But what our human emotions seem to require,” wrote James, “is the sight of the struggle going on. The moment the fruits are being merely eaten, things become ignoble” (http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Pajares/jsignificant.html). As humans, we need farreaching objectives, risks and determination; we also need mystery and metaphysics. Hicks shows that the Nazis were able to offer all these things to German society and that this offer was accepted.

How did this idealistic philosophy translate into the political programme of the National Socialists? Hicks answers this question in the third part of his book (pp. 15-26). He presents and succinctly characterizes five points of the Nazis’ programme. These are respectively: collectivism, economic socialism, nationalism, authoritarianism and idealism. The interesting thing is the similarities and differences between the Nazi programme and the communist one. Both programmes are close to each other as far as the attitudes to private property and individual economic initiatives are concerned. Both the National Socialists and communists were hostile to these things. Hicks cites a fragment of Hitler’s speech from 1927, significant in this respect.

“We are socialists, we are enemies of today’s capitalistic economic system for the exploitation of the economically weak, with its unfair salaries, with its unseemly evaluation of a human being according to wealth and property instead of responsibility and performance, and we are all determined to destroy this system under all conditions.” (Hicks, 2014, p. 17).

The differences between the two programmes, however, were essential. While communists promoted internationalism, proletariat class solidarity and, ultimately, the abolition of nation states, the Nazis emphasized ethnic and racial differences between people. According to them, “the major battle is between different racial and cultural groups with different biological histories, languages, values, laws, and religions. The battle is between Germans—with their particular biological inheritance and cultural history—against all other racial cultures.” (Ibid, p.19). At this point it is worth returning to the question of idealism. Hicks notes that in the case of the National Socialist it also meant contempt for traditional politics. For Hitler and Goebbels, ordinary, parliamentary and democratic politics meant simply “jostling”; it lacked grandeur and idealism. That is why they rejected it and in its place they introduced the programme of the nation’s moral renewal, where calling for the ultimate sacrifice replaced tedious procedures to achieve compromise.

Following Hicks’s argument from the point of view of Polish philosophical tradition, we cannot forget to mention the criticism of irrationality by Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz. This thinker, a representative of the Lvov-Warsaw School, noted that people who adopt irrational concepts, for example in politics, take great risks. For they have no intellectual tools to predict what these concepts may lead to. In some way, they surrender themselves into the hands of charismatic leaders, not knowing whether they are altruists ready to make sacrifices and focused on the welfare of others, or selfish cynical egoists taking advantage of the confidence of others to implement their private interests; whether they want to serve people, or to use them. Therefore, Ajdukiewicz concludes, from the social point of view it is safer to reject irrationalism. “[A] rationalist’s voice is a healthy social reaction,” writes Ajdukiewicz, “it is an act of society’s self-defence against the dangers of being taken control of by uncontrollable factors, among which there may be both a saint preaching of revelation, as well as a lunatic proclaiming the products of their morbid mentality and, finally, a cheat wishing for evil and selfish purposes to gain followers for certain views and mottoes” (Ajdukiewicz, 2003, p. 52). The example of Nazism shows that it is a true opinion. Hicks, who at no time during his narrative, even when writing about ideals which inspired the Nazis, loses sight of the horrific and inhuman consequences to which this ideology eventually led, would certainly sign his name under it. A clear warning on his part is also the mention that the liberal-democratic system guaranteeing societies peace and opportunities of development is, on the background of human history, an exception, and not a rule.

Let us now move on to the issue contained in Hicks’s title, namely Nietzsche and his responsibility for National Socialism. This is a complex issue. Ending the part of the book devoted to the exercise of power by the Nazis, Hicks again highlights the role of philosophy in the formation of the ideology of that power; he warns his readers against considering Nazi intellectuals as “mediocrities” (pp. 52-53). They were not uneducated people, who followed in the dark accidentally encountered ideas; nobody manipulated Adolf Hitler or other influential Nazi ideologues. Many party leaders could boast degrees from prestigious German universities, also in the field of philosophy. In the same passage Hicks confirms Hitler’s favourable interest in the figure and thought of Nietzsche.

“In his study, Adolf Hitler had a bust of Friedrich Nietzsche. In 1935, Hitler attended and participated in the funeral of Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth. In 1938, the Nazis built a monument to Nietzsche. In 1943, Hitler gave a set of Nietzsche’s writings as a gift to fellow dictator Benito Mussolini” (Hicks, 2014, p. 50).

The question to what extent Nietzsche’s philosophy influenced the formation of Hitler’s views certainly remains open. Hicks does not claim to be able to finally resolve this issue (hence, probably, the subtitle of the book – A Personal View – which emphasizes that the author’s interpretations do not necessarily have to be shared by others). However, taking into account Hicks’s thesis as mentioned above, i.e., that what inspired the Nazis was the philosophy, one should look at all the evidence of the proximity of beliefs of the National Socialists and Nietzsche’s views with the utmost attention.

Hicks presents Nietzsche’s views in Part Five of his book. The reader will find a brief presentation of the fundamental theses proclaimed by Nietzsche. For philosophically educated people these things will not be anything new, but the advantage of Hicks’s approach is the clarity and systematic method of exposition. The author does not focus on too meticulous analyses, or juxtapose numerous, often conflicting, interpretations of the views of the German philosopher, but avoids, so to speak, “splitting hairs”. As a result, his thought is at all times clear and the argumentation remains in close contact with the purpose of the book as expressed in the title. Thus, on pages 55 to 74 we familiarize ourselves with the concepts of the death of God, nihilism, master and slave, slave morality and the Overman. Each of these concepts is thoroughly presented, interpreted and referred to its text sources. Saying that Hicks does not go into too meticulous analyses does not mean that he proposes a simplified reading of Nietzsche. On the contrary, focusing on the most important issues, he helps us to reject many of the existing simplifications. One of them is the belief that Nietzsche had acted with absolute hostility to the Jews. Hicks explains that the attitude of the German philosopher in this regard was more complex. It is true that he held the Jews (and also the Christians) responsible for the emergence and triumph of the morality of slaves, which he himself opposed. On the other hand, however, he did not hide his recognition for the Jews who managed to survive despite such unfavourable conditions accompanying their lives in the course of history.

“Here Nietzsche says the Jews asked themselves some very realistic, practical questions about morality. If it is good to survive, then what policies and actions will keep you alive? And if you happen to be a slave, how does one survive as a slave?” (Ibid, p. 64).

The parts of the book which are of key importance for the understanding of the impact of Nietzsche’s philosophy on the ideology of National Socialism are parts six and seven. In the former, under the title Nietzsche against the Nazis, Hicks highlights those thoughts in the philosophy of the German philosopher which are in clear opposition to Nazi beliefs. And thus, according to Hicks, Nietzsche’s philosophy cannot be reconciled with the National Socialist version of racism, according to which the Germans occupy a unique position among racial and ethnic groups. “Nietzsche clearly is using the lion analogically and comparing its predatory power to the predatory power that humans of many different racial types have manifested.” (Ibid, p. 79). Next, contrary to what is generally believed, Nietzsche’s opinion of the Germans contemporary to him was not at all favourable: “between the old Germanic tribes and us Germans there exists hardly a conceptual relationship, let alone one of blood.” (Ibid, p. 77). According to Hicks, it would also be questionable to hold Nietzsche responsible for the Nazi anti-Semitism, for promoting the image of the Jews as wicked people, as well as for the fundamental diversification of the approach to Judaism and Christianity. Therefore, if the Nazis had wanted to find in Nietzsche justification for their beliefs about the inferiority of the Jewish race, the moral poverty of representatives of that race, and the superiority of Christianity over the Jewish religion, they could certainly not have done that. On this basis, we can say that to identify the whole ideology of Nazism with the philosophy of Nietzsche is a misunderstanding. Nietzsche certainly would never have shared many of the points of the programme of Hitler’s party.

On the other hand, we do find in the philosophy of Nietzsche a few themes that are identical with the ideology of the Nazis. In Part Seven of the book, under the title “Nietzsche as a Proto-Nazi,” Hicks lists the following themes: 1) anti-individualism and collectivism, 2) a conflict of groups, 3) instinct, passion and anti-reason, 4) conquest and war, and 5) authoritarianism. In the case of these issues, the reading of the work of the German philosopher would certainly provide the Nazis with many arguments in favour of their actions. Among the themes mentioned by Hicks attention should be paid to anti-individualism and collectivism. The common belief has it that Nietzsche is regarded as an individualist, but Hicks writes: “in my judgment his reputation for individualism is often much overstated” (Ibid, p. 87). Hicks’s argumentation at this point (pp. 87-92) deserves a thorough analysis. The author poses three questions allowing us to determine whether in the case of a given philosophy we are dealing with individualistic or collectivist orientation. In Nietzsche it is the latter that clearly dominates. It is, as I said, surprising, since it is community in the form of bourgeois German society that became a major object of Nietzsche’s criticism. Hicks notes, however, that in criticizing his contemporary society the German philosopher placed himself not in the mainstream of individualism, but different collectivism. “As Nietzsche says repeatedly, “Not ‘mankind’ but overman is the goal!” Nietzsche’s goal is a collectivist one—to bring about a new, future, higher species of man—overman. This is the significance of his exhortations about the Übermensch, the overman, the superman.” (Ibid, pp. 89-90). The importance of this point cannot be overestimated. Hicks notes that, despite the appearances of individualism, Nietzsche was in fact a collectivist. He represented the dominant line of continental thinking taking its origin in the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, which highlighted the existence, above an individual, of a superior being more important than the individual, both in ontological and ethical terms. The Overman would therefore be a species, and not an individual, i.e. it is mankind that should undergo a fundamental change, and not its individual representatives. I took up this theme in my article “Postmodern Dialectic of Social Care,” referring to Gertrude Himmelfarb’s interesting analyses.

From the point of view of Polish society, which a quarter of a century ago freed themselves from the state of political and economic enslavement, and is still on the way to define their own identity, the ending of the book can be very helpful. The author reflects in it on whether we have a good understanding of the philosophical assumptions of Nazism and whether, therefore, we will be ready to oppose it when it decides to return in one form or another. According to Hicks, however, understanding the ideals of Nazism is not enough. We also need to know well what we are in favour of ourselves, what our philosophical assumptions are, and what ideals we pursue. The last sentence of the book reads: “I will end on a provocative note: The Nazis knew what they stood for. Do we?” (Ibid, 2014, p. 107). This question should still be posed in our part of Europe since while we knew well that we did not want to live under the yoke of communism, we do not always know what model of life we want to implement after regaining freedom. As Isaiah Berlin would say, we have won freedom in a negative sense, but do we know what it is to look like in a positive sense? Hicks’s book, like many other American books referring to the recent history of Europe, carries a clear message. Only liberal and democratic principles guarantee security and development, mutual respect and individual success. Liberalism, however, does not belong to the most popular intellectual orientations in Central and Eastern Europe. Moreover, in the opinion of many it is something dangerous and ruthless, as it makes the individual count only on themselves. There were many causes that contributed to the consolidation of this belief. There is no place here for deciding to what extent it is true. But let us say that reading Hicks’s book puts us in a sense in a situation with no way out. For what in fact is an alternative to individualism and liberalism? The American author says that it is collectivism and authoritarianism, which combine concepts such as irrationality, conflict and socialism (Ibid, p. 97). None of them will necessarily lead either conceptually or, a fortiori, in practice to Nazism, but do they provide an opportunity for self-realization of man?

Hicks argues that they do not. Self-realization requires individualism, rationalism, entrepreneurship, freedom and capitalism. The example of Nazism shows that the rejection of these values, even in the name of great community ideals, leads to the tragedy of many individuals and peoples. We return here to the question of ideals and their understanding by William James. While it is important to pursue one’s own ideals, James argued in On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings, one has to pay heed not to impose them on others. “Hence the stupidity and injustice of our opinions, so far as they deal with the significance of alien lives.

Hence the falsity of our judgments, so far as they presume to decide in an absolute way on the value of other persons’ conditions or ideals” (http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/ Pajares/jcertain.html). Hicks seems to follow the same trail. His book is an absolute critique of political programmes which subordinate the freedom of the individual to the good of society, nation, or race. At the same time, Hicks is aware that individuals need great challenges, risks and personal success. It appears from many other publications of the American philosopher that the area in which individuals could safely implement their ideals is entrepreneurship.

The book Nietzsche and the Nazis. A Personal View is addressed to a wide audience of readers; a sophisticated philosopher, a teacher sensitive to philosophical issues, or a school student thinking reflectively will certainly read it with great interest. Such a wide range of potential readers does not mean that the book is superficial. On the contrary, it is a deep study, supported by solid preliminary literature research and the author’s thorough consideration. However, it is accessible, which attests to the author’s great respect for the reader. To write about very complex issues in a clear and distinct manner, ensuring precision of the concepts used, is a great skill which Stephen Hicks presented to the highest degree.

Bibliography:

Ajdukiewicz, K., Zagadnienia i kierunki filozofii. Teoria poznania. Metafizyka. [Issues and directions of philosophy. Epistemology. Metaphysics.] Kęty-Warszawa 2003.

Hicks, S.R.C., Nietzsche i naziści. Moje spojrzenie [Nietzsche and the Nazis. A Personal View], translated by I. Kłodzińska, Chojnice 2014. Second edition published by Museum of the Second World War, 2019.

James, W., Źródła znaczenia życia, [What Makes a Life Significant?], Pewien rodzaj ślepoty w człowieku [On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings] [in:] idem, Życie i ideały [Life and Ideals] translated by P. Kostyło, Bydgoszcz, 2010.

Kołakowski, L., Główne nurty marksizmu [The Main Currents of Marxism] vol. 1-3, Warszawa 2009.

Kostyło P., Postmodern Dialectic of Social Care, [in:] idem (ed.) Social Problems in English Pedagogy After 1989, Bydgoszcz, 2011.

Zielińska, H., Czy konieczna była pedagogika nazistowska? [Was Nazi Pedagogy Necessary? [in:] Absent discourses Part V, Kwieciński, Z., (ed.), Toruń 1997.

Zientkowski P., Teoria praw człowieka i jej krytyka w filozofii Fryderyka Nietzschego [The Theory of Human Rights and its Critique of the Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche], Chojnice 2013.

[1] The question of the relationship of Nietzsche’s philosophy with National Socialism is one of the topics of Przemysław Zientkowski’s book under the title The Theory of Human Rights and Its Critique of the Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (Chojnice 2013). cf. also Zielińska, H., Was Nazi Pedagogy Necessary? (Absent discourses Part V, Kwieciński, Z., (ed.), Toruń 1997). M. Wędzińska’s review of Hicks’s book discussed here will be soon published in “Forum Oświatowe” [“Educational Forum”].