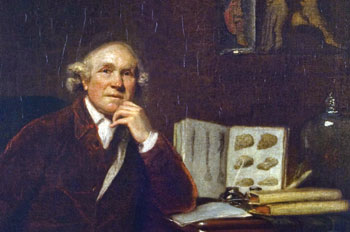

I posted earlier on The Knife Man and John Hunter, the great 18th-century anatomist and surgeon. In Hunter’s era surgery was brutal, in large part due to surgeons’ ignorance of anatomy, and in that earlier post I wondered:

Why there was still such ignorance of anatomy given that the 1700s were two centuries after Andreas Vesalius and a century after Francis Bacon?

My hypothesis: Philosophy has a lot to do with it.

Suppose that you are an early physician — your patients suffer and die, and you don’t know why. One option is not to think much of it: Bad stuff happens, people die, accept it. It takes an active mind — curiosity, interest, follow through — for science to get going. Why do people die?

Even if you do decide to think about it, there are further obstacles.

One is the historically common belief that the gods cause things to happen. That metaphysical belief will stop you from looking for natural, anatomical causes.

If you reject religious cause-and-effect and suspect that the cause might be anatomical, there are aesthetic obstacles — imagine the sights you will see, the textures you will feel, and (probably the worst) the odors you will smell.

There are moral obstacles: Anatomy seems to disrespect the dead or the living person the corpse once was. Moral obstacles might also be based on particular religious metaphysical beliefs, such as the resurrection of the body and so wanting to preserve the body intact for that eventuality.

So philosophy — that is, metaphysics, morality, and aesthetics — can stop the impulse that leads to anatomy. And based on some or all of the above, there will be legal obstacles.

In addition to those obstacles, all of which were operative in early modern Europe, consider the epistemological barriers.

One was the reverence for tradition. Religion emphasized tradition, and the Renaissance respect for the ancients’ accomplishments often meant merely substituting Greek or Roman authorities for Judeo-Christian ones. For example, the early moderns’ understanding of the inner workings of the human body derived from the mostly unquestioned authority of Galen’s humor theory.

Even to the extent that early scientists were willing to think independently of traditional authorities, many simply speculated and spun theoretical just-so stories. An example here is Albrecht von Haller, a Swiss contemporary of John Hunter’s, who — based on no observational evidence — argued that every embryo was from day one already a perfect miniature of the mature organism and that embryonic development was merely a matter of increasing size.

And to the extent that anatomy was done, it was most often performed as a demonstration of traditional or speculative theories. Students would crowd around the anatomist while the professor read from the authoritative text telling the students what they were seeing. This usually meant that top-down confirmation bias merely reinforced the traditions and speculations.

So early anatomy was hobbled by three faulty epistemologies:

Tradition — the unthinking acceptance of others’ thinking.

Speculation — thinking independent of observation.

The demonstration method — observation only as the hand-maiden to thinking.

A revolution in thinking was needed. The primacy of observation: that epistemological principle had to be articulated and institutionalized. That is what Francis Bacon did for philosophy in the 1600s and what John Hunter did for anatomy in the 1700s.

Empiricism made anatomy possible. Anatomy made internal surgery possible. Surgery made dramatic live-saving and life-improvements possible. Conclusion: Philosophy is very practical.

Related: My episodes on Francis Bacon and Galileo Galilei, in the Philosophers, Explained series.

My posts on Aristotle on the aesthetics of the “humbler animals” and Francis Bacon as the founder of modern philosophy.

Wendy Moore’s The Knife Man: Blood, Body Snatching, and the Birth of Modern Surgery [Amazon’s site].

Sherwin Nuland’s Doctors: The Biography of Medicine [Amazon’s site]. I love the chapter on Vesalius.

[This is an updated re-posting of Anatomy and Philosophy, 2009.]