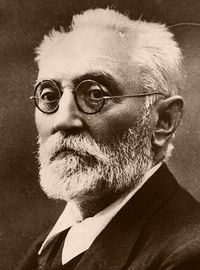

From the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno’s 1913 The Tragic Sense of Life, on how Kant first destroys rational belief in the existence of God but then resurrects that belief on moral grounds. Or: how Kant’s head says No to God but his heart says Yes. Or: how mortal man cannot find God but the immortal soul demands him:

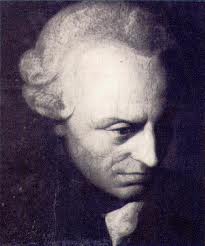

“Take Kant, the man Immanuel Kant, who was born and lived at Königsberg, in the latter part of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth. In the philosophy of this man Kant, a man of heart and head — that is to say, a man — there is a significant somersault, as Kierkegaard, another man — and what a man! — would have said, the somersault from the Critique of Pure Reason to the Critique of Practical Reason. He reconstructs in the latter what he destroyed in the former, in spite of what those may say who do not see the man himself. After having examined and pulverized with his analysis the traditional proofs of the existence of God, of the Aristotelian God, who is the God corresponding to the ζωον πολιτικον, the abstract God, the unmoved prime Mover, he reconstructs God anew; but the God of the conscience, the Author of the moral order — the Lutheran God, in short. This transition of Kant exists already in embryo in the Lutheran notion of faith.

“The first God, the rational God, is the projection to the outward infinite of man as he is by definition — that is to say, of the abstract man, of the man no-man; the other God, the God of feeling and volition, is the projection to the inward infinite of man as he is by life, of the concrete man, the man of flesh and bone.

“Kant reconstructed with the heart that which with the head he had overthrown. And we know, from the testimony of those who knew him and from his testimony in his letters and private declarations, that the man Kant, the more or less selfish old bachelor who professed philosophy at Königsberg at the end of the century of the Encyclopedia and the goddess of Reason, was a man much preoccupied with the problem — I mean with the only real vital problem, the problem that strikes at the very root of our being, the problem of our individual and personal destiny, of the immortality of the soul. The man Kant was not resigned to die utterly. And because he was not resigned to die utterly he made that leap, that immortal somersault, from the one Critique to the other.

“Whosoever reads the Critique of Practical Reason carefully and without blinkers will see that, in strict fact, the existence of God is therein deduced from the immortality of the soul, and not the immortality of the soul from the existence of God. The categorical imperative leads us to a moral postulate which necessitates in its turn, in the teleological or rather eschatological order, the immortality of the soul, and in order to sustain this immortality God is introduced. All the rest is the jugglery of the professional of philosophy.

“The man Kant felt that morality was the basis of eschatology, but the professor of philosophy inverted the terms.”

Exactly.

Kant’s philosophy initially incorporates many dualisms — reason versus desire, reason versus belief in God, reason versus morality. The dualisms, he thinks, are irreconcilable. So he faces a stark choice: the beliefs of desire/God/morality or the beliefs based on reason. He chooses the former. And that requires a subversion of reason. Hence the project of the first Critique and his happily denying knowledge to make room for faith.

Philosophically: the religious Kant dominates the philosopher Kant.

Historically: Kant is best — that is, most fundamentally — categorized as a counter-Enlightenment thinker who opens the door to the nineteenth-century irrationalisms of Schleiermacher, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and others.

Source: Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life. A Project Gutenberg version is online here. See Chapter 2 of my Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault for the critical importance of the Kantian turn in philosophy to the developments that led to postmodernism.

Related: Introduction to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, in the Philosophers, Explained series:

The postulates of pure practical reason would I think be more straightforwardly – and honestly – be labeled articles of faith.

As I see it the categorical imperative was the central doctrine of Kant’s system, for which The Critique of Pure Reason established the foundation.