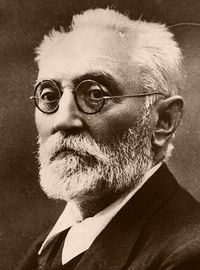

From philosopher Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life, which I re-read for the first time since my undergraduate days. Note these arresting lines:

“A human soul is worth all the universe, someone — I know not whom — has said and said magnificently. A human soul, mind you! Not a human life. Not this life. And it happens that the less a man believes in the soul — that is to say in his conscious immortality, personal and concrete — the more he will exaggerate the worth of this poor transitory life. This is the source from which springs all that effeminate, sentimental ebullition against war.”

So, if I am reading that correctly, atheists will be more likely to be against war and the religious will be more likely to be for war.

Filling in the gaps: Atheists do not believe in a soul that survives bodily death, so they don’t believe in an afterlife, so they believe this life is all there is, so they believe this life is most important, so they will be more opposed to life-threatening things like war.

Conversely: Theists believe that they have souls that survive bodily death, so they believe in an immortal afterlife, so they believe that this temporary physical life is less important than the afterlife, so they don’t care as much about physical death, so they are more willing to go to war.

Note also that opposition to war is described as “effeminate” — implying that real men favor war.

And note also that this was published in 1913, just before the Great War harvested many souls.

Of course there are other facets of religion that may increase or lessen warlikeness. But focus only on this one for now — the belief or not in the immortality of the soul. Is Unamuno correct to argue that that belief is directly relevant to one’s willingness to die in war?

Source: Chapter 1 of Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life (1913). A Project Gutenberg version is online here.

Related: Pacifist philosopher William James’s socialism-and-national-service solution to war. In the Philosophers, Explained series.

Religion inflates the currency of life: time. In reality, our time is limited. But of what importance are the few years on this earth we have in comparison with an eternal “life” in the “afterlife,” a euphemism for death. The more consistent religionists, such as many Islamists today, do say that they love death as others love life. They mean it. They’ve got nothing, but a few less than ideal years on earth, to lose, and all the time in eternity to gain.

If this is the case, shouldn’t atheist societies be less warlike?

There aren’t many self-professed atheist societies to act as the sample (since human beings seem to be hard-wired for belief), but I would think that the old Communist Bloc provides a pretty good example. I see little evidence that they were less warlike, less willing to sacrifice themselves, than their contemporary nations. Unless, that is, you believe their propaganda and ignore all the Russian “advisors” who got involved in every little proxy war.

Men go to war and persist at it when they perceive that there is something greater than themselves at stake. Family, home, or nation are often the motivation. To be remembered and honored for one’s sacrifice is probably consolation enough, with or without an afterlife. That’s one of the reasons military units take special care to honor their dead, why regimental flags have the names of centuries-old battles embroidered on them, why societies erect war monuments. Because the memory of heroic sacrifice (or, conversely, long-lived scorn for the traitor or coward) is important to the soldier’s will to endure.

Conversely, if your hypothesis is true, shouldn’t believers in a religion be relatively more susceptible to suicide? Or more likely to engage in pleasant but risky behaviors, knowing that heaven awaits? Again, a cursory search for data shows no examples of this.

My reading of the quote is not atheism vs religion but reason vs faith. One cannot believe that this life is transitory and the soul eternal without faith as there is no rational evidence to support it.

As I’ve grown older and hopefully matured I’ve realized that at times what I had thought were my weaknesses were my strengths and what I had thought were my strengths were my weaknesses.

Machismo is a kind of caricature of masculinity originating in defensive insecurity. I think authentic masculinity is nurturing of and enriching to women as well as itself; machismo is often abusive to women and self-destructive (“so I tells my bitch to…”). Authentic masculinity is capable of both toughness and tenderness; machismo fears tenderness because it is unsure of its toughness. (I get tired of tough guys with their tough talk and their tough clothes and their tough dogs and their tough music and their tough cars under which hide insecure boys struggling to become men. But feel for them too, particularly those from the ghetto, as they have so few male role models, often none but the hyper-exaggerated caricatures of movies and games).

Ludwig von Mises noted that many of the German armchair generals who glorified war were sickly men who would not long have survived in the conditions they advocated. He observed, “There is no record of a socialist nation which defeated a capitalist nation. In spite of their much glorified war socialism, the Germans were defeated in both World Wars.”

To glorify war, not in defense, but as a primary value, seems to me akin on an individual basis to glorifying the barroom brawler, thug and psychopath. All are parasitical of the roots of human survival.

As a former Marine and a Roman Catholic–yes. The Spartans, the most warlike tribe of the Greeks, had the idea of theosis. Theosis presupposes a life with god after death. Death doesn’t scare us.

Look at all the martyrs. Easily gave up their lives. Immortality of the soul was a Platonic idea. Was part of Orphism which was a part of Doric philosophy. Socrates was quite dismissive of death. He absolutely wanted to go.