“I esteem it above all things necessary to distinguish exactly the business of civil government from that of religion and to settle the just bounds that lie between the one and the other.”

Lecture Three: The Promise of Individual Empiricism. John Locke

Themes: Empiricism. Tabula rasa. Individualism. Liberalism. Toleration. Church and State. Henry VIII. Shakespeare. Galileo. Descartes. Milton. Cromwell. Newton. Texts: Locke: Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, Two Treatises of Government, A Letter concerning Toleration.

About the Instructor

Stephen R. C. Hicks, Ph.D., has been Professor of Philosophy at Rockford University, Illinois; Visiting Professor of Business Ethics at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.; Visiting Professor at the University of Kasimir the Great, Poland; Visiting Fellow at Harris Manchester College of Oxford University; and Visiting Professor at the Jagiellonian University, Poland.

In 2010, he won his university’s Excellence in Teaching Award.

Dr. Hicks is author of Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault, Nietzsche and the Nazis, Entrepreneurial Living, Liberalism Pro and Con, and Eight Philosophies of Education. He has published in Business Ethics Quarterly, Review of Metaphysics, and The Wall Street Journal. His writings have been translated into twenty languages.

About the Course

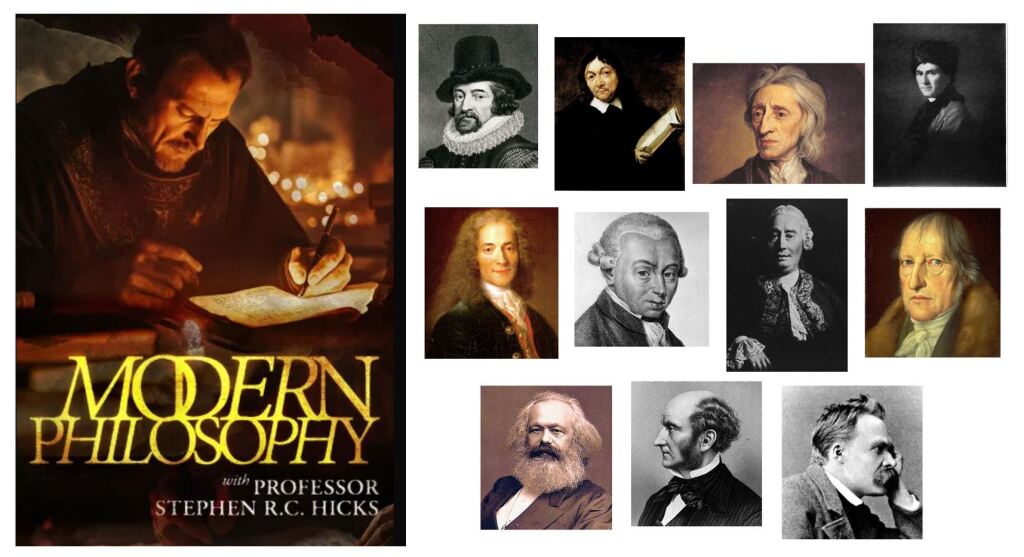

In this eight-lecture course, Professor Stephen Hicks guides us through the Enlightenment and the Counter-Enlightenment, including philosophers Francis Bacon, René Descartes, John Locke, Voltaire, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, Georg Hegel, Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill, and Friedrich Nietzsche. For each, Dr. Hicks establishes the philosopher’s context, presents his or her most influential arguments, and quotes directly from the philosopher’s important works.

Course trailer and enrollment options at the Peterson Academy site. Professor Hicks’s other courses — Postmodern Philosophy, Philosophy of Politics: From the French Revolution to World War II, Philosophy of Politics: From the Cold War to After 9/11, and Modern Ethics — are coming soon to Peterson Academy.

Locke separated church and state, but he certainly did not separate Biblical revelation from reason. He drew heavily upon Judeo-Christian teachings with regard to property in land, and elaborations on “The land shall not be sold forever, for the land is Mine” [Leviticus 25:23] in his discourse “On Property” in his _Second Treatise._

I emphasize this, because so many libertarians, perhaps unintentionally, have misrepresented what Locke had said.

In the first paragrah [§25], Locke notes that “natural reason” is in line with the “revelation,” “that God, as king David says, Psal. cxv. 16. has given the earth to the children of men; given it to mankind in common.” He then reconciles property in land with Biblical teachings, leading to what Robert Nozick dubbed “The Lockean Proviso,” that land can be held by natural right, only when “there is enough, and as good, left to others.” Locke referred to this proviso 15 times in 26 paragraphs.

In [§31], he invokes the correlation between God and natural reason again, “God has given us all things richly, 1 Tim. vi. 12. is the voice of reason confirmed by inspiration. But how far has he given it us? To enjoy. As much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labour fix a property in: whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others. Nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy.” This is the other Lockean proviso.

He noted [§32] that “God… commanded man… to subdue the earth, i.e. improve it for the benefit of life, and therein lay out something upon it that was his own, his labour.” This was the beginning of a conditional property in land, subject to the two Lockean provisos.

Locke made it clear [§34] that the Lockean proviso did not merely apply at the point of appropriation, but applied to land previously appropriated: “He that had as good left for his improvement, as was *already* taken up, needed not complain, ought not to meddle with what was *already* improved by another’s labour: if he did, it is plain he desired the benefit of another’s pains, which he had no right to, and not the ground which God had given him in common with others to labour on, and whereof there was as good left, as that *already* possessed, and more than he knew what to do with, or his industry could reach to.”

He also went on to show that the growth of population [§35] and the introduction of money [§36] tempted people to violate those provisos by holding parcels of land in order to be paid to let go of them. Libertarians incorrectly presume that he was saying his own provisos no longer mattered, which makes no sense given the degree to which he emphasized those provisos. Rather, he was pointing out that the growth of population and the introduction of money led people to violate those provisos, which was in conflict with both Biblical revelation and natural reason.

Locke mentions God several other times, and makes extended Biblical references in §38, that there was still enough room for Abel’s sheep no matter how much Cain tilled, and even in the time of Abraham and Esau, and goes on to note that this was no longer the case.

He noted that property by social compact [§45-51] had superceded natural rights where money had been introduced, but does not say these compacts are morally correct. Indeed, he concludes that, “This left no room for controversy about the title, nor for encroachment on the right of others; what portion a man carved to himself, was easily seen; and it was useless, *as well as dishonest,* to carve himself too much, or take more than he needed.”

So, what would be a moral vs. immoral social contract given practical considerations? Locke alludes to this in _Some Considerations on the Lowering of Interest and the Raising the Value of Money_

“It is in vain in a Country whose great Fund is Land, to hope to lay the publick charge of the Government on any thing else; there at last it will terminate. The Merchant (do what you can) will not bear it, the Labourer cannot, and therefore the Landholder must: And whether he were best do it, by laying it directly, where it will at last settle, or by letting it come to him by the sinking of his Rents, which when they are once fallen every one knows are not easily raised again, let him consider.”

Thus Locke is advocating a tax on the rental value of land, rent being a precise measure of the extent to which the Lockean Proviso has been exceeded. He does this on purely practical grounds, but his acquiescence to to social compact overriding his provisos was also on purely practical grounds.