Here is an example of a phenomenon that has long puzzled me: Nasty in-group fighting. In The Rise of Neo-Kantianism, Klaus Christian Köhnke asks:

What can “explain one of the most distressing features of the neo-Kantians: the fierceness and bitterness of their polemics, the nastiness of their ad hominem arguments, which destroyed personal friendships and decent collegial relations? Heinrich Rickert (Heidelberg) wrote to Paul Natorp (Marburg): ‘Just because we critical idealists agree on fundamentals, we have to take the knives to each other” (Cambridge University Press 1991, p. x).

It’s easier to understand demonizing the far opposition, i.e., those whose beliefs and values are alien to your own. But it’s harder to understand demonizing those with whom you agree on 99% of key issues. Why does the 1% disagreement drive some to paroxysms of anger, bitter infighting, and denunciation?

The infighting dynamic crops up in a variety of types of movements across history — political movements (e.g., the Marxists), educational (e.g., the Montessorians), architectural (e.g., Frank Lloyd Wright’s followers), philosophical (e.g., Objectivists), semi-scientific (e.g., Freudians), and of course most religious movements.

Heinrich Rickert above stated it as an imperative: The closer the agreement, the worse the fighting. Why is that so?

* Is it that we expect or hope for more from those close to us, so disagreements are more crushingly disappointing?

* Is it that those close to us have more power to hurt us, so disagreements lead to defensive over-reactions?

* Is it that movements are social, so disagreements are opportunities for in-group status advancement or for signaling one’s status and alliances?

I can understand the phenomenon more easily within systems that have strong faith-and-authority epistemological traditions. Such groups do not make reasoning and healthy argument habitual, so it makes sense that their members would not be able to handle questioning and disagreement well.

But that makes more puzzling the in-fighting among rational belief systems, i.e., those that explicitly identify and urge productive argument and discovery skills. In those groups, is the descent to nastiness simply a failure of character? Or are there strong psychological and social-psychological dispositions that even rational belief systems have a hard time overcoming? Or is the initial impression of great amounts of infighting distorted — that actually most of the group’s members handle the disagreements productively and in proportion, while only a few noisy participants drown them out and drag down the discussion?

A related question about leadership: Does a movement’s leader typically contribute to the in-fighting problem, or do the followers do it all by and to themselves?

One datum: In discussing Freud’s fractious movement, Howard Gardner tells this sad anecdote:

“Less happily, their involvements with Freud proved costly for some individuals, particularly those who had broken with him. Freud’s young protege Victor Tausk, despondent over his recent rupture with the unforgiving Freud, committed suicide; of the earlier followers, at least six others ultimately did the same. These facts represent our first evidence of the casualties that tend to befall those within the orbit of highly creative individuals” (Creating Minds, p. 82).

But I was struck by this contrasting datum about Frank Lloyd Wright’s circle, as recalled by Ayn Rand after a visit:

“She long remembered her indignation over the attitude of hero worship and servitude that Wright was famous for instilling in his ‘Fellowship,’ made up of tuition-paying students. They cooked, served meals, and cleaned. They ate at tables set a step or two below the dais on which Wright and his guests and family dined, and they consumed a plainer diet. Their drawings, she noted, were undistinguished and imitative of Wright. ‘What was tragic was that he didn’t want any of that,’ Rand told a friend in 1961. ‘He was trying to get intellectual independence [out of] them during the general discussions, but he didn’t get anything except ‘Yes, sir’ or ‘No, sir’ and recitals of formulas from his writing.’ She compared them to medieval serfs” (Anne Heller, Ayn Rand and the World She Made, pp. 169-170). And of course some of Rand’s followers have behaved that way too.

Nietzsche said that one must always forgive an intellectual his first generation of followers. It seems a sorry truth of history that those who grow up directly in the shadow of a genius have special difficulties with becoming independent.

So it is still a puzzle in my mind. Great matters demand great thinking and great passion — and great character in the exercise of both.

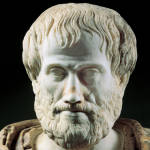

About justifiable, virtuous anger, Aristotle stated the ideal best: To be able to “feel anger on the right grounds and against the right persons, and also in the right manner and at the right moment and for the right length of time” (Nicomachean Ethics 4.5, 1125b 31). That is indeed the challenge.

Related: In Belgrade, Serbia, Stephen Hicks and Craig Biddle debated whether Objectivism is open or closed.

Excellent post. Good food for thought. But I am most disturbed by the fact that people actually killed themselves over Fraud (Freud).

Great collection of data about different movements. And, of course, I share your distress and wonder and what motivates these fractious fracturings, especially in ideologies that expound reason.

Could the emphasis on moral righteousness move even philosophies of reason to more religion-like features?

You might have added the Impressionist painters and the Russian nationalist composers.

I see it ecologically. The greatest threat to a sub-group is a sub-group that occupies its ecological niche. If conservatives are the defenders of capitalism, then the good arguments of the libertarians are not heard; if the libertarians are the defenders of capitalism, then the good arguments of the Objectivists are not heard; if this (bad) sub-group of Objectivists are the defenders of capitalism, then that (good) sub-group of Objectivists are not heard. The narrower the differences, the more precisely one’s niche is occupied, and thus the fiercer the fighting between the two groups tends to be. The dynamic does not begin to reverse until co-existence between the groups is no longer seen as a zero-sum game.

Roger Donway has captured a key element of my thinking, frustration. Ayn Rand once commented that capitalism’s conservative defenders were its worst enemies, threatening its practice. Marx railed against those claiming to be Marxists.

Infighting does not imply that both sides are at fault. A telling observation is, “With friends like these, who needs enemies?” Supposed friends acting as enemies. Who would not be mad? The spy is resented more than the enemy soldier.

If you are defending a view against opposition, you resent most those creating confusion or misrepresenting your view. You may have more contempt for the opposition, but your frustration is with those you thought to be comrades. They are betraying you, the idea, the mission.

As an extreme sense of betrayal, I noted the assassinations of John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, and Martin Luther King were all by leftists, not right-wing opponents or racists. I assume the killers felt their cause was being betrayed by what they saw as compromises by these leaders? The assassins had once pinned their hopes on these leaders, now double-crossed. Infighting of a sort, perhaps only in the minds of the killers.

Early leaders of a movement may be threatened by followers who challenge ideas. Freud experienced this, as well he should, since most of his views could not withstand even cursory questioning. Denouncing others was all he had to defend himself. (His valid contribution was recognizing that the mind was a manifestation of one’s biology, not simply its content. But he misunderstood both.)

Fans with shallow understanding, eager to follow and even join charismatic leaders, like Freud, will often feel unworthy and rejected when rebuffed. Their inadequacies in grasping the leader’s views or the cause of rejection may create feelings of both resentment and guilt. Feeling that they are unfit for the movement, ousted by the new associates with whom they sought to throw their lot, and ridiculed by those opposed to the movement, their self-esteem plummets, and suicide the only refuge.

Clear opponents of our views and values are not people we associate with. They do not have our respect. They are not being listened to by our friends and associates. Their views do not threaten us or challenge us intellectually. We are psychologically supported by friends and associates of like mind.

My resentment of Obama is strong. His threat to my property, liberty, and pursuit of happiness is great. But he does not threaten me morally or intellectually – my self-esteem, my friendships. I have no interest and see no point in engaging him intellectually, much less carrying on an intellectual fight. My interest and activities will be in gathering support from more rational individuals and in pursuing association with them.

Everyone feels intellectually frustrated, threatened, and even betrayed by others at times. Some amount of infighting is natural, working out ideas. Not a problem. These are the people with who we expect an mostly agreeable, mutually supporting relationship. But when significant riffs develop, resentments and frustrations will naturally be highest.

The acrimony of deteriorating marriages illustrates the effect. Acrimony seeking support from friends and family.

Roger Donway’s point about competitors in an ecological niche is perceptive. I have long had a related explanation:

Observe the behavior of followers when a leader in a movement is excommunicated by another leader in the movement. There is confusion, uncertainty about who is right, existential fear, violent internal conflicts that mirror the external conflicts, and desperate attempts to force people (or internal viewpoints) to pick a side and quash the opposing side.

In the investment markets, there is an old saying, “Uncertainty is worse than bad news.”

Observe further that the degree of conflict is directly proportional to:

1. how similar the views are

2. how high up in the hierarchy the excommunicated leader is

3. how dependent the follower is on leaders to tell them what to think.

One isn’t much threatened by views that are:

– radically different (and thus easily dismissed as “obviously wrong”)

– held by people low in the hierarchy

– easily rationally shown to be false.

What this reveals is that the emotional violence is generated by *epistemological uncertainty* combined with a *lack of confidence* that one has the ability to independently resolve the conflict on the basis of rational evidence, rather than on the basis of emotional claims of authority.

Not being able to rely on one’s own independent judgment, one has nothing to fall back on but the judgment and authority of others—hence the desperate clamoring for “who is right”, and the battle to portray one’s own emotionally chosen view as “the truth from on high” and alternative views as “sacrilegious”.

The solution is to personally practice, and for leaders to model, calm in the face of uncertainty, benevolence to all sides, commitment to reality and truth, and patient, rational exploration of the issues. Not easily done, but eminently worthwhile.

Excellent, Johann.

Where does the failure of philosophy lie?

In poetry

My Name is Nobody Soundtrack (Main Title) : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vkF1Axc1-jU

🙂

Being is only through poetry. It is through poetry that being is. It has no existence outside of it. Philosophy is an imposture of poetry. And I will prove it to you.

There is no being that exists outside of poetry. What makes being exist is poetry. Not philosophy. For the poet is the worker of being.

The proof is the Torah.

There is no being. There is poetry that generates being.

Being, the concept of being is linked to poetry.

There is no being without poetry.

It is poetry that reveals being.

Not philosophy.

Simon & Garfunkel – My Little Town (Audio) : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__Ro3eGuznI