Interview conducted at Rockford University by Stephen Hicks and sponsored by the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship.

Part I

Hicks: I am Stephen Hicks; executive director for Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship at Rockford University and our guest today is Timothy Sandefur. Mr. Sandefur is senior staff attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation based Sacramento, California, and he is an expert on property rights, economic, liberty issues and Constitutional issues. Mr. Sandefur is here at Rockford University today speaking on the theme of market entrepreneurs versus political entrepreneurs and many of the legal and Constitutional issues in American political history.

Let me ask you, Timothy: This distinction between market entrepreneurs and political entrepreneurs that was the basis for your talk. What is that distinction?

Sandefur: Well, a market entrepreneur, is a person who seeks to make a living and pursue happiness by productivity, by creating a product or a service and using the opportunities that the market provides to trade freely with other people that desire that product or service. Whereas a political entrepreneur is a person who tries to enrich himself by the use of the state’s power of coercion. And that needs a person who tries to obtain monopoly privileges or to use licensing laws or other legal restrictions on competition. I often say that Walmart, for example, could make itself a lot richer by making Target [stores] illegal. And to do that would be political entrepreneurship as opposed to the economic entrepreneurship or the market entrepreneurship of selling products and services that people want for prices that they are willing to pay.

Sandefur: Well, a market entrepreneur, is a person who seeks to make a living and pursue happiness by productivity, by creating a product or a service and using the opportunities that the market provides to trade freely with other people that desire that product or service. Whereas a political entrepreneur is a person who tries to enrich himself by the use of the state’s power of coercion. And that needs a person who tries to obtain monopoly privileges or to use licensing laws or other legal restrictions on competition. I often say that Walmart, for example, could make itself a lot richer by making Target [stores] illegal. And to do that would be political entrepreneurship as opposed to the economic entrepreneurship or the market entrepreneurship of selling products and services that people want for prices that they are willing to pay.

Hicks: In American economic history, there always have been market entrepreneurs and political entrepreneurs, but you put American economic history in context, talking about an evolution over the course of the last two centuries — from the economy being primarily based on market entrepreneurship to an increasing role for political entrepreneurship or an increasing dominance of political entrepreneurship. And a number of legal and political issues were central to your story. One was the issue of the priority of liberty or democracy in American politics. How does that, the decision whether liberty or democracy is primary, relate to that set of issues?

Sandefur: It’s a big question. To put American legal history into a simple narrative could be very misleading. So, it can only be done in big, broad brushstrokes. But I think that, over the course of 200 years, the general trend that we’ve seen is a society that began organized around, in principle at least, organized around the individual right to pursue happiness without unreasonable interference by other individuals or by the state. And gradually, that has transformed itself into a society where government is basically seen as the orchestrater of economic and business activity in the country.

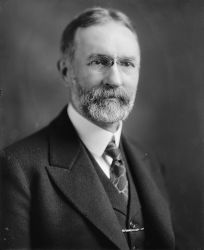

The reasons for that are philosophical. Largely, primarily in fact, today, the effects that we see today are primarily the result of the Progressive movement which began in about 1880 and led until, well, I would argue, that we are still living in a Progressive era. And the political principles that the Progressives believed in and imported into American law are responsible in large part for the expansion of government interference in the market: government deciding whose business should prosper, whose business should not prosper, how property should be rearranged and adjusted to meet the changing needs of the day to quote Justice Louis Brandeis, a leading Progressive.

The idea that government acts as a kind of gardener or sculptor who shapes society to be what political leaders believe it ought to be and, as that principle became primary in American political and legal arena, what you see as a result of that is, naturally, people respond to that atmosphere by investing their time and energy to persuade the government to give them the favors, right? If the government is in the job of deciding who is going to prosper by handing out licenses, or imposing tax burdens on people, or imposing restrictions on businesses and things, then people are going to fight among themselves for the opportunity to use that power for their own benefit. And so really what you see is that the trend from market entrepreneurs to political entrepreneurs is largely a consequence of the philosophical change that has taken primarily in the 20th century.

Hicks: Would you say, again, painting broad strokes , that for the first century in American economic history, the dominant view was that government’s job was to protect individual liberties? And the Constitution, for example, had a number of restraints on democracy and that was its primary purpose?

Sandefur: Exactly.

Hicks: But by the time we get to the beginnings of the Progressive era in 1880s, there has been a shift there …

Sandefur: That’s right.

Hicks: … that the job of the government is to do what democracy wants — that is to say, majority rule given primacy over protection of individual liberties, so then it becomes a matter of who is most effective at wielding or influencing the government and the government’s power in the marketplace.

Sandefur: That’s exactly right.

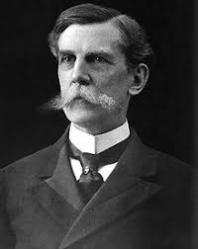

Hicks: You mentioned Progressivism’s mission and some progressive intellectuals, such as John Dewey, in your talk and also progressive jurists with some qualifications all over Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis in next generation also was a key figure here. So from the 1880s on through the early part of the 20th century, there is an increasing dominance of Progressivism and we add to that the cataclysm of the Great Depression. In what way did the Great Depression cement Progressive philosophy in American economic life?

Sandefur: Well, that’s a very big question. It starts out with — if you contrast the American founders — you have the role of government with our own view today of the role of government. The American Constitution begins by declaring explicitly that liberty is a blessing. The Declaration of Independence says explicitly that we are born with liberty and we create government in part to protect liberty and when it violates that right, then we can overthrow the government if we have to in order to change it and protect our liberty. Contrast that with today’s perspective which holds that liberty is basically whatever the government allows us to do. Rights are permissions that are given to us by the society as a whole, for societies’ own purposes, and that shift was made by Progressive-era philosophers.

Now, John Dewey, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis, and other intellectuals of the period — you can debate whether they should be called progressives or not — but, they were pragmatists philosophically, and politically, they supported the progressive-era movement which was designed around expanding government control over individual rights. In fact, overthrowing the concept of individual rights and replacing it with government centralized planning in terms of giving people rights; we are taking those rights away to meet the changing needs of the day.

Now, John Dewey, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Louis Brandeis, and other intellectuals of the period — you can debate whether they should be called progressives or not — but, they were pragmatists philosophically, and politically, they supported the progressive-era movement which was designed around expanding government control over individual rights. In fact, overthrowing the concept of individual rights and replacing it with government centralized planning in terms of giving people rights; we are taking those rights away to meet the changing needs of the day.

Now, that with a gradual progression from the 1880s to the 1930s or so. But it became a very prominent element of the legal academy, of the philosophical academy until, by 1934, in a book called Recent Political Thought by Francis Coker, who is, I believe, a Harvard professor. Coker comes out and says “Hardly anybody believes that there are such things as individual rights anymore and everybody believes that governments exist to control what goes in society.” And that shift was done by the progressives and it was done in various terms: the most important one of which was the idea that rights are not natural rights, they are not something that we entitled to because we are human beings, but they belong to us because of our membership in society and society controls, stretch, or destroy those rights to meet, to serve the interests of the majority in society.

Hicks: So, we have a 50-year transition period philosophically from the 1880s to the 1930s, and then we start then to see landmark legal cases instantiating that new philosophical outlook. In your talk, you had two broad categories of economic impact. One involving occupational licensing, the other involving price fixing and other economic controls. Just one or two in each category, what would you take to be the most significant Supreme Court cases in each of these categories?

Sandefur: Yeah. The New Deal era, the decade of the 1930s, which I believe the poet Yeats call “the Low Dishonest Decade,” saw a dramatic shift in American law that some historians characterized it as the shift in time that saved nine, as the famous phrase. And it’s often said that in 1936 or 1937 the Supreme Court dramatically changed how it understood the nature of economic rights and private property. That is really an oversimplification. What happened was that, beginning primarily, I would say, in 1934, you saw the Court increasingly adopting this very broad, watered-down interpretations of Constitutional clauses that allowed the legislature carte blanche to do what it wanted. The case that I focus on primarily is Nebbia v. New York in 1934, which upheld a New York law setting a minimum prize for the sale of milk. And it was in that case that the Court abandoned the old legal theories that it had used in protecting business against abuse of regulation and instead adopted, basically, an anything-goes attitude that they called the “rational basis” test, and that still prevails in the law today. And under the rational basis test, laws are virtually never held to be unconstitutional, and this test is what is applied when it comes to economic rights or private property rights.

There was another 1934 case called Home Building and Loan Assoc. v. Blaisdell, and on the Blaisdell case what the Court did was, again, it basically washed its hands on a very important clause in the Constitution, the contracts clause, which says that no state may infringe on the obligations of contract. In the Blaisdell case, the state of Minnesota passed a law that just unilaterally extended the period of time for redeeming mortgages, because there were a lot of foreclosures going on in the Great Depression. So, this law was passed.

Well, this is one of the main reasons the Constitution was written: was to stop laws like these. If you look at the history of the Constitution, the Shay’s Rebellion that inspired the writing of the Constitution in part was because of laws like these that were depriving creditors of their opportunity to get back the money that was due to them. So, Minnesota passes its law, goes up to the Supreme Court whether it’s Constitutional and the Supreme Court said “Well, the contracts clause doesn’t mean today what it meant in the older days. And, you know, if the founders had known about the Great Depression, they wouldn’t have written that clause anyway and so it’s okay.” And so you have really the finest example of living Constitutionalism as it is called, which really consists of blasting large holes in the Constitution and eliminating Constitutional clauses that get inconvenient.

Justice George Sutherland, one of my heroes, dissented in the Blaisdell case, and he said that “If we do not uphold the Constitution when it pinches as well as when it comforts, then we might as well throw the thing in the fireplace.” Well, what you see in the New Deal era is the triumph of Progressive-era thinking that really is alienated from the Constitution — it has nothing to do with the classical liberal principles of the Constitution — and that required large parts of the Constitution to basically being rendered null and void. And so the due process of law clause, the Public Use clause in the Fifth Amendment, the Contracts clause, and the Commerce Clause gets completely revised, I mean, you find the Constitution dramatically altered during the period of basically the 1930s.

Justice George Sutherland, one of my heroes, dissented in the Blaisdell case, and he said that “If we do not uphold the Constitution when it pinches as well as when it comforts, then we might as well throw the thing in the fireplace.” Well, what you see in the New Deal era is the triumph of Progressive-era thinking that really is alienated from the Constitution — it has nothing to do with the classical liberal principles of the Constitution — and that required large parts of the Constitution to basically being rendered null and void. And so the due process of law clause, the Public Use clause in the Fifth Amendment, the Contracts clause, and the Commerce Clause gets completely revised, I mean, you find the Constitution dramatically altered during the period of basically the 1930s.

Part II

Hicks: Another element of your talk involved the occupational-licensing issue which, in terms of its public rationale, the purpose of licensing is to protect the public from unscrupulous, snake-oil salesman. But either because of the political operation or the looseness of the laws, it has really become a rent-seeking vehicle or a protectionist vehicle. How does that play out?

Sandefur: Well, what happened is that, because of the rational-based status that the Court created in the Nebbia case in 1934 — and that it continues to apply to this day in cases involving occupational licensing — it’s virtually never that a Court will strike down an occupational-licensing law, it’s unconstitutional. So legislators are pretty much free to do whatever they want. And when legislators are free to do whatever it wants, that means that political coalitions are going to be formed in order to pass laws that benefit those political coalitions. That’s a basic insight of Public Choice economics.

And the Founding Fathers were very familiar with this idea. We talk about it as though it’s a recent development in economic science, but Federalist 10 and 51 talk about the problem of factions and that’s exactly the same issue. The Constitution was written to prevent this problem, and there are all sorts of clauses that prevent it, primarily, the Due Process of Law clause, in the Fifth Amendment, and again, the Fourteenth Amendment. These clauses are supposed to prohibit the government from passing laws that benefit particular interest groups at the expense of other people, without any actual connection to the public welfare.

Now, when an occupational licensing law actually protects the general public, as in medical licensing in the famous case of Dent v. West Virginia, the Supreme Court upheld that law, even though that was a period of time before the rational-basis test, when economic liberty was taken seriously. But what we’ve got now is occupational licensing laws that have no connection to public wealth and safety, that really just exist to shut down fair competition.

The primary example of this is a case in the state of Oklahoma where it’s illegal to sell coffins without being a licensed funeral director. Now, this requires two years of training and tens of thousands of dollars to get this license. This law doesn’t protect the general public. It exists to protect those who have funeral licenses from fair competition by entrepreneurs who have a better idea and want to compete at a lower price. And the court, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals said that is perfectly okay, even though the law has no connection to the public health and safety. It’s okay for the legislature to hand out these kinds of economic favors.

Hicks: So we have a philosophical shift early in the 20th century that led to a shift in the legal landscape, and the shift in the legal landscape enabled a whole series of political entrepreneurs, including rent-seekers.

So we are now in a situation, on your analysis, where the legislature in the United States is free to do what it wants. pretty much, on economic issues and the Court is turning a blind eye having gutted those economic limitations, based on legislative powers.

If we then go from philosophical change to legal change to our current business climate, which has any number of unhealthy elements in it, in your judgment, how do we turn things around? Again, very difficult, but what I did like in your lecture, as a philosophy professor, is that there’s a big role for philosophy.

Sandefur: Absolutely. And really that is where it has to change, is philosophical change. It’s a very long, it’s a very long tale, you might say. When you look at the history of economic freedom, as a matter of law in America, you see that it took 50 years, from 1880s to 1934 before the progressive attack on individual economic freedom succeeded in the formation of the Nebbia case.

Well, it’s going to take at least equally as long to undo that if that’s what the American people decide to do. And to do that requires first us changing our attitude toward the role of government in our lives toward the meaning of liberty under the Constitution. What the Progressives did — the Progressives are very smart people, I mean, and we are talking about people like Oliver Wendell Holmes, who is unquestionably a genius — but what they did was they shifted the ground of political philosophy in this country by rejecting the principles of natural rights, by rejecting the foundation of American Constitutionalism. If you read Justice Holmes’s sentence in the Lochner case, for example, there is a line in there where he says: “A Constitution is formed for people with fundamentally differing views.” If you think about it, that is just absurd, that is totally insane, that’s throwing down a gauntlet to two and a half thousand years of western political philosophy, which holds that you can only have a Constitution among people with fundamentally shared views, right? The whole problem we are having in the Middle East is trying to form a Constitution among people with fundamentally differing views. You can’t even have a marriage with somebody with fundamentally differing views. How can you have a Constitution with them?

Well, the American Founders believed that you do have to have shared fundamental views, and where did they articulate those views? In the Declaration of Independence. They said, “These are the fundamentally shared views on which we are going to create the Constitution of the United States later.” They say, “We believe government exists to secure individual rights.” Then, a decade later, they come along with the Constitution that says “To secure individual rights we’re creating the Constitution.” They shared consensus on philosophical principles.

Holmes comes along in 1905 and says “Constitutions exist for fundamentally differing people.” And what they do, in his view, is channel the power of the majority and allow them to enforce their will on the minority. Instead of going to war with one another, we are going to use the vote to steal each other’s property and manipulate how society operates and dictate how other people can live their lives in a more peaceful way. That is Holmes’s attitude toward government. And really Holmes’s dissent in the Lochner case is the manifesto of Progressive-era legal theory. And that is basically how we live today, with some dramatic exceptions.

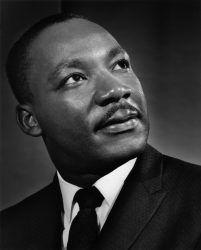

I would say that one of the saving graces of the 20th century is the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. If you look what the Civil Rights Movement was about — what Martin Luther King was accomplishing at that time — he was undoing a lot of what the Progressives had done philosophically. He was always insisting on the importance of the principles in the Declaration of Independence. He reiterated those principles time and time again, saying “We have to bring ourselves back to the wells that were dug deep by the American Founders in the Declaration of Independence.” He restored and he forced America to recognize the moral questions involved in the power of majority, and that was the questions the Progressives had tried to wipe away. They had tried to say that whatever the majority says is okay, and what and [MLK’s] followers helped to do was show us that, no, that’s not the case, the democratic majorities can be wrong. There are principles that are more important than majority will.

I would say that one of the saving graces of the 20th century is the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. If you look what the Civil Rights Movement was about — what Martin Luther King was accomplishing at that time — he was undoing a lot of what the Progressives had done philosophically. He was always insisting on the importance of the principles in the Declaration of Independence. He reiterated those principles time and time again, saying “We have to bring ourselves back to the wells that were dug deep by the American Founders in the Declaration of Independence.” He restored and he forced America to recognize the moral questions involved in the power of majority, and that was the questions the Progressives had tried to wipe away. They had tried to say that whatever the majority says is okay, and what and [MLK’s] followers helped to do was show us that, no, that’s not the case, the democratic majorities can be wrong. There are principles that are more important than majority will.

So, I think that what we saw in the 1960s was, in some areas of law, we saw a backing way from some of the worse elements of Progressivism.

And that’s why I characterize the defense of economic liberty as a civil rights movement: it’s part of restoring America’s recognition of the importance of wealth creation and the moral right of a person who creates wealth to that wealth.

And that’s why I characterize the defense of economic liberty as a civil rights movement: it’s part of restoring America’s recognition of the importance of wealth creation and the moral right of a person who creates wealth to that wealth.

Hicks: Nicely put. Thanks for being with us, today.

Sandefur: Thank you.

The video of the interview with Timothy Sandefur follows.

Part 1:

Part 2: