My discussion with Glenn Beck ranged over capitalism and socialism, the ethics needed for a free society, Greek virtues, intolerance and indoctrination in education, Ayn Rand’s egoism and her view of charity, whether a meaningful life requires transcending failure, the differences between Antifa and Nazi Brownshirts, whether the National Socialist really were socialist, postmodernism, whether Nietzsche’s “God is dead” is nihilistic or liberating, whether World War I was the cultural breaking point, Dadaism, Sigmund Freud, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, whether history repeats itself, how to return to constructive dialogue, should we be optimistic or pessimistic, and more.

The audio-only link is here, and the video versions are at YouTube.

Here is the transcript:

Glenn Beck: Let me start with questions that I don’t think the average American can give you a good answer on, three of them, alright? What’s socialism?

Stephen Hicks: Well, socialism is partly an ethos, and partly it’s politics. The ethos is that you belong to a social unit, not an individual self; your allegiance, your values, and in some cases, your identity comes from being a part of that social unit. Politically then…

Stephen Hicks: Well, socialism is partly an ethos, and partly it’s politics. The ethos is that you belong to a social unit, not an individual self; your allegiance, your values, and in some cases, your identity comes from being a part of that social unit. Politically then…

Beck: Does pure socialism go as far as Anthem or We the Living?

Hicks: Yes, that’s right. You are born into a social unit. That social unit shapes you.

Beck: You’re a cog.

Hicks: Well, you can become a cog. And your job is to perform a function in that social unit. Now, that’s an ethic, but if you politicize it, then whatever authorities wield the power in that society can use you and direct you for social ends, primarily. The individual doesn’t exist or exists only to the extent that he or she is performing a social role and can be used by the political authorities for that purpose. So, the political formulation usually is the collective ownership of the means of production, but the core means of production is a human being. So, the human being is owned by the collective and should be used by the collective.

Beck: What is capitalism?

Hicks: Capitalism is a more variably defined thing. If you take capitalism as the opposite of socialism—and I think that’s one legitimate usage—then you say it is an individualistic ethos that I make myself. I am responsible for myself. The values that I pursue in my life should be mine, and then I enter into social arrangements, family, friendships, business, and sports voluntarily. The purpose of the power institutions in society is to protect individuals as they pursue their lives. And so that would imply the economic portion of that, which is an economic free market, and that typically is capitalism. Now, capitalism is more slippery here. Sometimes capitalism is meant only to refer to an economic system, where we have private property, free exchange, and so forth. Sometimes it’s used more broadly to mean liberal individualism, and that’s the contrast to socialism.

Beck: Between the two of them, it’s easier to sell socialism because, as Jonathan Haidt would say, we all share the care/harm platform or pillar together. We want to take care of people. Capitalism just leaves you out there in the cold, and socialism is about making sure we all make it across the finish line together, right?

Hicks: I think socialism is, in its political form, a perverted version of the care principle that you talk about. So, I think we do have care for others. We do have a natural benevolence, but it’s not automatic. Infants, right from day one, size up people they are interacting with. And if the person is a basically decent human being then, of course, we form positive attachments. On the other hand, if the infant senses that this person is not treating me appropriately, and then we start putting barriers and the care doesn’t happen. So I think most of us, as human beings, want to give people the benefit of the doubt initially. So we’re open to care and open to forming relationships, but it does have to be earned in some sense.

Beck: So, there are many routes to socialism. It can start from, “I’m a nice person, and I want everybody to get across the finish line,” as you put it, and, “I am afraid of what might happen to me, if I fail in my life, and I can also empathize with other people who are not doing well with their lives, so I just want the problems solved.” And in many cases, socialism is just a knee-jerk, “I want this problem solved instantly,” and the best way to solve the problem if it’s an economic problem is to take money from people who have it and give it to the people who don’t have it. Now, I think that’s a plausible explanation for some avenues toward socialism, and it can come out of that care and healthy benevolence.

What’s the difference? Is Canada a socialist country or a capitalist country?

Hicks: I don’t think it’s socialist. I think the way to do this is to say any culture is made up of any number of sub-sectors. So you can say, “Here’s the economy, here’s how we do family, here’s how we do religion, here’s how we do our leisure activities, and here’s how we do our politics.” And so an overall label like capitalism or socialism is going to try to capture each of those. I think, for the most part, Canada would be classified as an individualistic, freedom, capitalistic country. We make our own, I’m born in Canada, raised in Canada so…

Beck: Right. I heard you say “out.”

Hicks: Yes, that’s right, and now I’m down here in the south.

Beck: Yeah, it’s the South.

Hicks: I’ll just throw that out there. [chuckle] So there’s no socialism [in Canada] with respect to your dating life or your love life. You’re perfectly free to date whomever you want and to get married or not to whomever you want, so that’s perfectly liberal individualist in the proper sense of the word. Religion also is done entirely liberal individualistically. Make your own choices, start your own church, and do whatever you want. People can consume whatever media they want. If you are a poet or a filmmaker or a writer, you can do pretty much anything that you want. All of those things are very much free-market, individualist, liberal capitalist, and so on. Then if we focus on the economic sector of society, I think you would have to say Canada is a mixed economy. It has a significant number of capitalistic elements, but it also has a significant number of socialistic elements as well.

Beck: The same with Sweden.

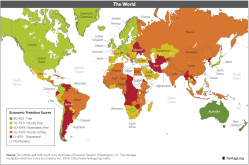

Hicks: The same with Sweden. There are 190 or so countries around the world, and we have these new social science indexes that come out and measure this, that, or the other thing. On economic freedom, Canada and Sweden are all in the top 10% of nations around the world. They got there by largely being free-market-capitalist-oriented nations, but because they’ve become so rich, they can now, to some extent, afford some redistribution, some more interventionist, and in some cases, outright socialistic measures.

Beck: What is the difference between that and state capitalism, like China?

Hicks: Well, I think state capitalism is a misnomer. It comes out of a corrupted intellectual tradition. So if we go back and say that capitalism means individualism, then China is out. What people on the left have wanted to do because of the terrible track records of most socialist regimes is, to say that the countries that failed with socialism weren’t really socialist. They assign all of the corruptions and the things that go wrong to capitalism. So the move that they’re making is to say that if you put economic concerns at the top of your social hierarchy, then that scale of values makes you a capitalist; you’re prizing that rather than some other social thing that you could achieve. And then from that categorization scheme, if you then say, “Well, individuals can do this money making,” then you’re a free-market capitalist. If you think the government should take care of the economy and money making, then you have state capitalism. But I think that’s a miscategorization from the beginning.

Beck: What’s the difference between socialism and communism?

Hicks: Communism is a subspecies of socialism. It’s a bit like saying someone’s a Christian and then immediately you’ve got Catholic, Presbyterian, Eastern, and so forth. So the broadest version is socialism where you say people belong to society, people should serve society, and society’s organizers—the politicians—should be managing all of society. Communism is one particular subspecies of that. Marx’s name for it was scientific socialism, or communism. Now, what he means by the science in scientific socialism—that’s another avenue that we can go down. He is contrasting his version of socialism with earlier religious forms of socialism where we are monks and we hold all of our property communally, sleep communally, eat communally, and don’t have any personal possessions. And then earlier Utopian socialisms from Saint-Simon, Proudhon, and Rousseau to some extent…

Beck: Right here in Dallas. Dallas is the first socialistic experiment in the United States, if you take away Jamestown and even some of the Pilgrims, but…

Hicks: I’m not familiar with that one. Of course in the upper Midwest there’s a whole number of socialistic experiments as well: New Harmony, Indiana, and others. So Marx and Engels were trying, in the middle part of the 1800s, to distinguish their version of socialism, which they thought was more materialistic and more scientific from the other earlier versions of socialism.

Beck: Any time this has ever worked and didn’t end in death and totalitarianism?

Hicks: Well, if you think that monasteries and convents are a kind of communalistic or socialistic experiment, then you would say that they can work.

Beck: What about at a country-size? We’re not all volunteering to go serve God. I think I’m a Christian, so if Jesus comes back and rules over the earth, it probably will look very socialist. We’ll all be putting our money in a big pot, and everybody will only take what they need because we’ll all be honest. That is a great Utopian idea, but when you actually put men in charge, and you’re dealing with a large society, has it ever worked?

Hicks: Well, I don’t think it’s a great Utopian idea. I do think it’s bad in theory, but your question is about whether it’s working. No, it has never worked on any large scale.

Beck: Why do we keep trying it?

Hicks: Well, that’s because it has nothing to do with economics, politics, or any historical understanding. I’ve talked with socialists over the years, and what I’ve learned is that no socialist ever comes to socialism by studying economics deeply. No socialist says, “I have studied the history of socialism, I’ve figured out what the flaws are, and I know it’s going to work this time.” None of them have done a serious study of political governance. They’re focused on morality. They think it is moral.

In the lead-up to the Soviet Union falling, most socialists of that time would say, “No, it’s not going to work practically, but I think it’s moral and I still believe it. Okay, maybe we have to make some moral compromises with capitalism and allow markets to some extent, but we’re going to rely on some socialistic ethos as our guiding principles and we’re going to try to forge a middle ground. So for the practicality, yes, we’ll have to deal with the capitalists, but we’re going to get our morals from socialism.” I think they believe in a certain conception of justice, fairness, and decency that is very different from the individual, liberal conception of justice, fairness, and decency. It’s a moral collision, and that’s where the battle I think really has to be fought.

Beck: I think I’m going to get there in two questions. First, socialism would be the exact polar opposite of, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” correct?

Hicks: Well, yes, if you take what the founders meant by those principles.

Beck: What they meant was, “Nobody’s a king over anything, and nobody has a right that somebody else doesn’t have.”

Hicks: That’s a political equality.

Beck: Right. So socialism is the exact opposite of what we have or what our founders were striving for in our mission statement in the Declaration?

Hicks: Yes. The founders were individualistic, so all of the rights that they hold to be inalienable here are for the individual. They’re largely drawing on a Lockean tradition. Each individual, according to Locke, should be free in his own person, in his conscience, and in his property. All of those are individualistic rights, but we all hold them equally.

Beck: And when you’re in a socialist society, who is the grand holder of rights or the bestower of rights?

Hicks: Well, I think rights language ultimately has to go out the window, because you can’t say you have a claim against anybody else. To say that you have a right is to say that something belongs to you, and then that puts a boundary against everyone else, including the State. So the Bill of Rights, for example, is a limitation on what states can do, the individuals…

Beck: So when…

Hicks: Well, let me just finish this point. So the socialists are saying you have no rights with respect to the community. There are no boundaries that you can put against the community, so you don’t have rights. Instead you have obligations; you have responsibilities to society.

Beck: So when a democratic socialist says, “Look, we’re just looking for some common sense tampering down of rights”, that’s dishonest?

Hicks: I don’t know. I’m inclined to give younger people the benefit of the doubt because they don’t know the history, the economics, and so on. But I would say if you are a college graduate and you are now intellectually mature and making public political claims, if you don’t know what you’re talking about and you’re still saying things, then there’s a kind of dishonesty there. You just haven’t done your homework.

Beck: Okay, right.

Hicks: I think most socialists who are more articulate, in their heart of hearts, know that they want power. They say, “Yeah, it’s going to be democratic but I’m going to be the one who gets elected,” or, “I’m going to be the wiser person who’s going to be wielding power on behalf of the community.”

Beck: Define freedom.

Hicks: Well, freedom is a negative. Political freedom is to say I’m not subject to a higher authority. And that then comes down to saying that I have zones in which I’m free to think and free to act. Whether I say something or do something, it is as a result of my initiative and not because of compulsion by some other authority. When you are in that state, then you are free.

Political freedom rests on a kind of understanding of what it is to be a moral human being, because rights are a moral claim. To say that, politically, we can’t do certain things to each other—that’s to understand that we want human beings to be able to act a certain way. We want people to be moral agents. Moral agency requires a notion of freedom because, if we’re just being pushed around by forces beyond our control, we’re not moral agents. So, a deeper understanding of freedom comes down to volition. I have a capacity that many other species do not have to regulate my own thinking and behavior, and because I have that capacity, I can be held responsible for it. I’m a moral agent, and being a moral agent has social implications. One of those social implications is that we have to respect people as moral agents and not try to treat them like animals.

Beck: So there’s Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Hicks: Yes.

Beck: The problem I think that we have now is nobody’s read the first volume of The Theory of Moral Sentiments. And can you have freedom that lasts? Can man rule himself? Can you have capitalism where the invisible hand doesn’t choke everybody to death? If you don’t have a set of what I would call Judeo-Christian values that help with self-governance, can you have that?

Hicks: No, absolutely not. If you think about it, a free society has to be the society that is most moral, because you’re giving people huge amounts of freedom to say you can do basically whatever you want. And your assumption really is an optimistic one. The optimistic assumption is that most people as individuals can get their act together and make something of their lives. If you leave people free, they can work things out together without their moms and their dads or a nanny-state telling them what to do. So you do have a very optimistic assumption that is built into any sort of free-market capitalism or liberal individualistic society.

And this is why, while socialism often has a reputation for being an optimistic Utopian view, I do actually think it’s based on very pessimistic assumptions about human beings. Socialism typically argues that there are so many people out there who are just so incompetent that they can’t run their own lives, and they need everybody else to chip in and look after them. Or if we leave people to their own devices, they’re just going to be at each other’s throats. We need them to have a big state to protect people from tearing each other apart. All of those are very pessimistic assumptions about human beings.

But, to cycle back to your point, you’re absolutely right. If you are going to give people a lot of freedom and a lot of responsibility, the assumption is that they’re going to be able to develop some sort of a moral code that will keep them going in the proper direction. Now, I’m much more of a fan of the Greco-Roman tradition than the Judeo-Christian tradition, on this point here, so I…

Beck: Which is what?

Hicks: The core virtues are, in the Aristotelian tradition, a kind of prudence or practical wisdom that individuals are capable of exercising their minds, figuring out the world around them, understanding their own appetites, regulating their own appetites, and then thinking in terms of principles so that when you and I start interacting with each other we can figure out what principles are going to work for us.

Courage is another important one in the tradition here. Life is challenging. There’s always the risk of failure, and so developing your capacity to be willing to think about the hard problems, to be willing to, in many cases, say that you’ve made a mistake—that’s an act of courage. You can change your mind, deal with other people who have different views, and let them criticize your views. If we’re going to have a free society, we’re going to have to have lots of conversations because we’re going to have to work out our differences through conversation and not through violence. Being willing to speak in public, to challenge other people, including people who have more authority, is an act of courage. So, the virtues of practical rationality, courage, temperance, being able to regulate yourself, are prized in the Greco-Roman tradition as well.

Beck: Tell me about Ayn Rand. I’m kind of all over the board. I’m libertarian for the most part, but when I read Ayn Rand, I love her philosophy and her writing, but I have a hard time understanding her. Anthem is one of my favorite books, but I don’t connect with her emphasis on ego. She has this view that charity is not necessarily a virtue. It seems very selfish. Can you debunk that or explain that?

Hicks: Well, sure. On the ego point, think about what makes your life meaningful. If you let other people choose your core values for you—what your musical tastes are going to be, what foods you like, what your clothing style is, who your friends are going to be, what your career is going to be, whom you’re going to date—none of these things, if they’re going to be meaningful, can be done for you. And if you shut down your ego and just let your mom dress you and your dad choose your spouse for you …

Beck: I think of royalty.

Hicks: Yes, or if you like music just because everybody in your social crowd probably likes that same kind of music, then you will not have a meaningful life. So, I think one of the points that Rand is insisting is that on all of the core values, including all of the social values like friendship, love, business acquaintances, and so forth, the pre-condition of those things working is that each individual involved has to see the value of it and choose that value for himself or herself. So, I think that’s the ego point.

Now, the second part of your question, though, is about charity. I think, according to Rand, charity is a minor situational virtue. And certainly, one of the things that’s outstanding about her is that she’s downgrading it from being a major virtue. In some traditions, of course, it’s the primary virtue. But I think the reason for that is that Rand does have a rather optimistic view about human beings, that human beings don’t need to be treated like charity cases. If you think about it, that is a kind of pejorative thing.

Beck: I would agree with that.

Hicks: I think for most of us who have some measure of self-respect, under what circumstances will you accept charity? It has to be in pretty desperate situations, and you’ve tried everything that you possibly can to not to put yourself in a charity situation. So, I think part of the assumption is that most human beings can, with effort, make a go of their lives, and they don’t need charity. And if you start from that assumption, then you say, “What is it that’s going to make it possible for people to make a go of their lives?”

What skills, habits, and attitudes do we need to encourage in ourselves and in other people? That’s going to be the focus of your ethics, not on how certain people just can’t solve their problems and fix their problems. Of course, there are going to be some people who fall between the cracks. They have bad luck, they make bad decisions, they’re orphans, the zombie apocalypse happens, or whatever. And in those cases, absolutely, if you’re dealing with a decent person who’s had a run of bad luck, that person’s your friend or there’s some sort of a non-profit charity out there, sure, be charitable.

Beck: You’re crippling people. You’re crippling people when you don’t allow them to fail.

Hicks: Absolutely.

Beck: Benjamin Franklin said, “The best thing you can do is make someone uncomfortable in their poverty.” I think they might stone him to death if he said that today.

Hicks: Certainly the political ethos has shifted, but that point about failure is right. Failure is part of life, and you’re not going to be actually living a meaningful life if you’re not putting yourself out on the edge and accepting a certain measure of failure. So, if from the get-go we say, “There’s not going to be any failure. No matter what happens to you, you’re always and automatically and instantly going to be bailed out” — well, then you’re setting people up for the more general failure of not putting together their own life on their own terms.

Beck: That’s where we’re at. We’re at a place now where the world is saying, “Too big to fail or too little to fail.” Guaranteed jobs, guaranteed houses, these are all the things that democratic socialists are now talking about, which I think is just corrosive to the soul.

Hicks: Yeah, absolutely.

Beck: But it’s kind; it’s so warm and fuzzy. I’m 54. I’m the really first generation that didn’t have to fight for something. I didn’t have World War II where we were fighting good versus evil. I didn’t fight the Soviet Union—the politicians fought that. Nobody’s picked me up by the jacket on political philosophy and thrown me up against the wall and said, “What do you really believe?” We now kind of just expect that it’s always going to be this way because it always has been this way. How do you get people to value what we have before we lose it, when everyone will go, “Oh, crap, that was pretty good actually.”

Hicks: Well, that’s a big problem, and it’s a parenting problem and an education problem. I think there is great value to being in such a successful culture that we can take that for granted and just get on with the business of enjoying our lives. But it’s also important to realize where that came from and what the preconditions of that are, that there is real evil out in the world, that success and progress are not automatic, and that all of the goodies that we are able to enjoy don’t just appear magically right from heaven.

We have probably two generations of people, our generation included, who haven’t had it that hard. We have not had to get down to the fundamentals and really think about what we are willing to die for and what we are living for. That value clarification, at a very fundamental level, probably hasn’t happened.

Beck: I look at this as the luckiest time for people to be, not only because it’s really good but because it has the potential of being very bad as well. And if it goes that way, we are going to have something that I haven’t had my whole life, and that is I get to find out for sure who I am; the best or the worst of me is going to come out. I’m an alcoholic. I would not be here if I hadn’t had my crash and decided to get back up. Can you be a full person, who you really are, without that crash or that real pain?

Hicks: I don’t know, but I think we can live the best life without necessarily having alcoholism or war forced upon us. I think all of us do recognize, in most areas of our lives, that if we are going to make them meaningful, we do really have to put ourselves out there. And relationships don’t work, for example, if you’re holding back and so we might all go through heartbreaks in our teen years and go through divorces and those test your mettle at a very deep level. And the same thing can happen in careers. If you really have some business aspirations, you start a business — you have to put yourself out there. Most entrepreneurs go through failures several times before they achieve the success. Because they have really put themselves into their business, it is a soul-wrenching experience to go through, no different than a failed marriage. I think it can also happen in religion where, if you are going to make your religion or your philosophical views serious, you can’t just be formulaically going through things; you have to put yourself out there.

Beck: It may not be the actual bottom or crisis. It’s just the risk.

Hicks: The risk always has to be there

Beck: I think that’s where the courage that we may be missing right now comes from. As a society, we’re not all that sure that we as individuals have anything great in there, and so many people hang on to their pain or their troubles or whatever, and that defines them. In order to learn, you have to come to a point where you say, “If I take this step and this is true, that means I’m going to change here, here, and here.” And you’re not sure. It’s why people sometimes don’t read things. They don’t want to necessarily know more, because they don’t want to change.

Hicks: So there’s a laziness or a lack of ambition that’s characteristic of lots of people.

Beck: Yeah, or a lack of courage because you don’t think that it’s going to be any better.

Hicks: Sure.

Beck: Tell me the difference between the actions of Antifa and the Nazi Brownshirts.

Hicks: If you let your eyes go out of focus just a little bit and you’re looking at the two groups, you don’t see very much difference.

Beck: You have to toe the line.

Hicks: Yes.

Beck: They will beat you in the streets if you don’t. It’s their way or the highway. They’re against whatever the other totalitarian idea of the time is. What’s the difference?

Hicks: You have a shut down of rationality. They’re past the point of saying discussion matters. They reject any sort of liberal, democratic, republican approach to politics. They’ve bought into a view that only forceful action is going to work. At the same time, they have people divided into groups. There are people who are in the in-group and people who are in the out-group, and anybody who is in the out-group is de-humanized from their perspective. You have to have a strongly de-humanized perspective of other people if you are willing to punch them in the face, hit them with a stick, and so forth. There also is a kind of cowardice that you wear your uniform, and you are losing your individuality by merging into the group. You don’t go out as an individual person; you travel in a pack, and you’re letting that group social psychology take over. And then you are deliberately putting yourself in situations where you’re trying to incite violence, and there’s the game of street-fighting chicken; who’s going to hit first? You might hit first, or they might hit first. You know somebody is going to hit first, and it doesn’t really matter to you. And whoever hits first, you’re going to just use the excuse that they were asking for it.

I don’t see a significant difference. The only significant difference, and I think this is on a second order, is that Antifa is, in its intellectual origins, not particularly ethnic or racist. It’s just a more generic approach to collectivism or some sort of socialism. But of course, the Brownshirts were socialists as well, so it really does come down to gang street-fighting, and that’s their political model.

Beck: Everybody calls them the Nazis, but they were the National Socialists. They’re considered to be on the European right, but in America, are they on the right or the left?

Hicks: Left and right doesn’t work and hasn’t worked for a long time. I think it’s fine to say that we’ll define some political spectrum, and then we can say there’s a left position and a right position. The first thing you have to do is say what you are trying to measure. Are you trying to measure individualism to collectivism? Are you trying to measure democratic procedures versus authoritarian procedures? What’s the left and what’s the right? The way we use left and right now is just, “There’s this bundle of beliefs over here and another bundle of beliefs over there.” There’s not necessarily any internal inconsistency in those bundles of beliefs, so it’s purely a journalistic labeling that’s just slapped on.

If we want to categorize the National Socialists, I think they were truthful in their labeling. They were nationalist and they were socialist. They did take the racial/ethnic identity of human beings to be a fundamental. They were not at all individualistic. You are born into a nationalistic group and an ethnic group that gives you your identity; you belong to it. Your national ethnic group is in competition, if not outright conflict, with all of the other national and ethnic groups that are out there. It’s a collectivism plus a conflict, so there’s zero individualism and zero understanding that you and I, if we are of different ethnic groups or different national groups, are both human beings under the skin and that we have the same values and can work things out in a win-win way.

So all of that very strong nationalism—they believe it—but that’s one kind of collectivism. The socialism, for them, meant a kind of an economic collectivism. There was no, “We favor private property. We favor free trade. We favor the free movements of people across borders,” and so forth. All of it was very, “There should be government management of the economy as a whole.” Goebbels loved Marx. If you read through the original Nazi party program from 1920 when the party was formed, of the twenty-five points in the program, fourteen of them are just straight socialistic demands: confiscation of profiteering, organization into cartels, government management of everything, government redistribution of wealth. So no socialist has any disagreement with any of those fourteen points. Those were formed in 1920, and all through the 1920s, they didn’t change any of that. When they came to power in the 1930s, they put them into practice. So in theory and practice, it’s a species of socialism.

Beck: Let’s talk about postmodernism, and I want to talk to you about it in this framework: I don’t think most Americans know, but we are not in the progressive era—we’re in the postmodern era. The progressives have been eaten by the postmodernists. Most people get up every day and they hear a new term or a new name or a new thing that they have to do or say or call somebody, and they hear how bad they were or some group was, and they don’t know where this is coming from. And without understanding, we’re playing into their hands, I fear.

Hicks: So understanding postmodernism.

Beck: Yes.

Hicks: Postmodernism is an important thing, but you’re also partly asking a demographics question. If we try to understand our era, and let’s focus on North America just to keep it relatively simple, then, I think you have ask what are the main beliefs that most people believe? I do think there are a lot of progressives out there and there are a significant number of postmodernists, and we’ll come back and say what that means. But I do think …

Beck: You’re very precise with words. You’re very much like Jordan Peterson. I don’t know what it is about you Canadians, but you’re very precise.

Hicks: Maybe it’s the nerd element.

Beck: What’s controlling the dialogue?

Hicks: I would say that we still are largely a modernist Enlightenment culture, but as we were talking earlier, a lot of that is taken for granted. It has a lot of cultural staying power, but it’s in our bones and we haven’t necessarily articulated what those principles are. Postmodernism now, for two generations, is the most articulate and most vigorous group, and they, to a large extent, are setting the terms. Since they are loud and since there’s a lot of momentum there, it is tempting to say we’re now into a postmodern era.

Beck: We are all being forced to live under this rule from a very small number of people. They’re dragging us into this, and we don’t even know where it is or what it is.

Hicks: That’s fair to say. The most active voices and the ones who are setting the terms of the discussion are coming from an alien philosophical and cultural framework called postmodernism. Since it is relatively new and since it is coming from some intellectual and cultural sectors that a lot of people never interact with, it does take them by surprise. There’s a lot of the brazenness and an extremity in some of those views. Now, of course, it is a huge topic. Any time you’re talking about postmodernism, then you have to say something about modernism. What the postmodernists are doing is reacting against and rejecting what they take to be the core beliefs of the last 400 or 500 years of what we call…

Beck: The Enlightenment.

Hicks: Yeah, modern history or the Enlightenment as the most articulate, mature expression of the values that have come to dominate in the modern world.

Beck: Empirical data, science, reason …

Hicks: And technology, individualism, tolerance for people, respect for the industrial revolution and its achievements, a kind of universalism that all human beings should have the same rights and so slavery is a moral abomination, the second-class status of women is a moral abomination. All of those…

Beck: Who actually believes those things are bad? How did they get there?

Hicks: Well, now we need to have arguments about five or six major philosophical issues.

Beck: I just can’t imagine how someone could see those things as bad. I understand we have lots of problems, but if you actually look at the world and you understand history, it’s getting better every day for people all over the world. So, how do you get there?

Hicks: Well, I think you can get there from a number of routes, but let’s just talk about one. Suppose we take a kind of political route. Suppose we say we’re going to have a kind of democratic republic. We’re going to say that all individuals have equal rights, life, liberty, property, and so on. And if we’re going to do a lot of things democratically, then what does that pre-suppose? Well, partly, it means that you believe that there is such a thing as a universal human nature, and that’s going to be one point of attack. Is there such a thing as universal human nature? Can we even articulate universal principles or not? And if we become skeptical about our capacity to think universally and in terms of very broad principles, then we’re going to start thinking smaller-scale and start focusing on smaller groups. And that’s going to be one dynamic.

But if you just think about democracy, why do we do democracy? That’s a very messy process. So, we say, “Well, the ideal of democracy is that every adult is going to participate in the process and have a say. We want people to vote, and we want them to vote in an informed way.” But how are they going to become informed? Well, we expect them to be able think about very complicated issues—foreign policy issues, environmental concerns, problems in the third world, and so forth. We expect that they can gather a lot of data and that they are willing to listen to arguments by people who have different political positions. We can run experiments, and this is the science part coming out. We’re going to give power to these people for a little while. We’re going to assess the results. Is it working or not? If we say, “I made a mistake four years ago in voting for this guy. I’m going to change my mind and I’m going to vote for these other people over here as well.” That’s a very optimistic, pro-reason view of human beings.

Beck: An amazing thing that it’s worked as long as it has.

Hicks: That’s right. So, democracy is, in part, coming out of the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment had a very optimistic assessment of the power of human reason and that it was, by and large, universally distributed across all individuals and that, with the right kind of education and the right kind of freedom, we can make people politically competent and that you’re going to get good results out of that process.

Now, all of the postmodernists stand at the end of a skeptical tradition that came out of my discipline, Philosophy, that by the middle part of the 20th century said, “Reason really is impotent. Reason really is a fraud, and that is not what drives human beings.” If you don’t think that people are rational or that reason is particularly competent, then your understanding of how politics has to be done has to change. It has to be done non-rationally.

As far as individualism is concerned, if you don’t think people are able to understand and respect universal principles of tolerance, dignity, and rights—if you think that people are really narrow-minded and what they believe is really shaped by more local, “selfish” kinds of concerns—then you’re going to say that it’s impossible that we can educate all human beings to believe in universal rights or that we’re all brothers and sisters under the skin. That’s just too pie-in-the-sky. What’s real is that people are parts of groups; that’s where their tribal loyalties are. And once you start believing that, you’re going to take politics in a very different direction.

Now, to understand why so many philosophers and people who are philosophically trained in literary criticism, law, and historiography came to be skeptical, we have to understand a long counter-Enlightenment story that starts back in the late 1700s and early 1800s. There were important philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Kant, in my understanding of the story, are having. The way I read it, and this is in my book, is that things move slowly in the academic world, but the skeptical arguments about the power of reason lost by the time we got to the middle part of the 20th century. Then, for a generation or so, philosophers and philosophically-educated people were kicking around, and we didn’t have a positive philosophical framework that grounded science and rationality, and that left a vacuum for various non-rationalist movements to gain some traction.

Beck: Explain the last part of that, because I’m not sure I know what non-rational means.

Hicks: We’re talking about collectivism, socialism, Antifa, and so forth—these are all movements that come out of the left, broadly speaking. So, by the middle part of the 20th century, that’s when the big shift is going from the old left to the new left. People who are of our age now are old enough to remember when the new left really was new and it was vigorous. But what was the new left all about? Well, it was about a splintering of what had been a kind of monolithic, neo-Marxist movement. Marxism really was the only game in town for the left for about a century. But when that came widely to be seen as a failure, including by people who were fellow travelers on the left, there was a lot of soul-searching on the left, and the left did splinter into a lot of new factions. That’s what the new left was all about, but a lot of it was anti-rational.

So, for example, think of Maoism, which became very popular in the 1960s. Maoism is a much more irrationalistic version of Marxism. We’re coming out of our Marxist traditions, but we think that Marxism was too wedded to rationality, logic, and science, and what we need to do instead is to not wait for rational, industrial, logical change and the march of history to occur. What we need to do is have strong assertiveness and will, and it’s going to be these non-rational, political energies that are going to cause the right kind of revolutionary change. You have people in the Frankfurt School who are explicitly saying that was what happened. And so Herbert Marcuse is an important person in the 1960s, a thinker of the new left, that capitalism, science, and technology have succeeded in taking over the world and normalizing things and giving us all of these goodies so that we’re comfortable working our nine-to-five jobs and then watching the TV and doing whatever it tells us, and we’re bought off by all of the gadgets, and so on.

If you’re going to retain any sort of humanity, you have to become an outcast, you have to try the drugs and the crazy sex, and you have to be willing to engage in criminal activities. You have to go in the Fight Club direction, thinking of the movie. That’s the way that we have to break out of what is too rational and too logical a system. And in the chaos, we just hope some sort of new form of collectivism, socialism, or whatever is going to emerge. It’s an explicit embrace of non-rational or irrationalist techniques, but that’s given space by the failure of the intellectuals who say that, “No, we can understand the world rationally, logically, and scientifically.”

Beck: I think it’s Foucault that is over in Paris in 1968, and they look at postmodernism a little differently than it had been looked at, correct?

Hicks: Who are “they” in this case? The French?

Beck: Yeah, the French philosophers.

Hicks: Well, again, postmodernism is a bit like saying Christianity. So immediately you then have to say there’s going to be Catholics, Protestants, Eastern Orthodox. There is a Foucauldian strain that is, I think, properly categorized as postmodern. So, yes, Foucault and his followers do look at things differently than the American versions and some of the other strands that are prominent in the subsequent generations.

Beck: It’s all really about deconstruction, right?

Hicks: Well, deconstruction is most associated with Derrida, and it comes out of literary criticism. It’s a way of reading texts.

Beck: Basically, I can put my words into that author’s mouth if I can draw the story-line together, right?

Hicks: Yes. The idea of deconstruction is to say, “When we are reading texts there is no such thing as an objective reading of the text. The text amounts to evidence, so we can come up with hypotheses, reject ones that don’t fit with all of the evidence, and come up with one that is the right or the best way to interpret a text.” What they want to argue, and this takes us into lots of technical issues in language, epistemology, semantics, and so forth, that says, “We think that language is much too fluid, much too indeterminate, and much too subjective, so there is no way to say there’s a right reading of a text.”

Beck: Even if you have the author saying, “This is what I meant”?

Hicks: Sure. Of course, then, one of the things we can just say is, “Well, authors can lie.”

Beck: There’s a famous painting of the Americans defeating the British, and there is a black man kind of hiding behind a white guy. Well, the black guy is Peter Salem, who was a very important player in the American Revolution. The painter at the time is on record saying, “That’s Peter Salem. He’s a hero in that battle.” The way it is now, this art is being taught in universities as, “No, that’s a slave.” He was a free man. “That’s a slave, and it doesn’t matter what the artist said at the time.”

Hicks: Right. Here we should say something about Freud, though, because one of the things that feeds into postmodernism via the Frankfurt School is the idea that surface pronouncements in our minds are not necessarily the real agenda. They can also be invisible to the speaker, so only the specially trained psychoanalyst or the specially trained critical theorist is the one who can know what’s really going on. I don’t know this particular interpretation of the Peter Salem issue, but the argument is certainly going to be that there’s a kind of false consciousness. We know better than the artist does himself.

Beck: If there was no Nietzsche and no Freud, would there have been the struggle of the 20th century, the way it was?

Hicks: That’s an interesting question.

Beck: The Germans were just this nasty, toxic brew of about forty years with all kinds of stuff mingling and mixing.

Hicks: Yeah, absolutely. I think Nietzsche and Freud are justly read for the reason they were geniuses; they were brilliant. I think we would have gotten there anyway; it just may have been different. Rather than saying that there’s one towering genius like Nietzsche who put it all together, effectively it may have been worked out by four or five individuals of second-tier statures, but there was a logic to the way the intellectual discourse was going, and Nietzsche put the package together.

Beck: Do I read it right, “God is not dead,” meaning, “Good luck. You’re going to have to replace him with something. What are we going to do next?” It’s kind of a warning, in a way. It’s not a celebratory, “God is dead,” is it?

Hicks: Well, I think it is.

Beck: Do you?

Hicks: Yes, I think Nietzsche is ultimately seeing that as an affirmation. His view is that God is dead, but he has, of course, a very negative view about religion. He thinks religion is a matter of saying, “We are not going to take charge of our own lives, and so we are expecting a higher being to legislate for us to keep us in line.”

Beck: Isn’t he also worried, though? People are people, and we have to be careful on what we put in the place of God.

Hicks: Some of us will put something in the place of God. He thinks most people, when they lose their faith, become less religious and don’t know what to do. Actually, he’s pessimistic about the broad range of human beings. They don’t have what it takes in order to actually put together a meaningful life for themselves, so they’re just going to wallow in some sort of mediocrity and, ultimately, nihilism. So he does see the 19th century that he’s living in as an era of bad faith where people don’t really have the old-style faith that gave meaning to their lives, but they haven’t really abandoned it. They kind of go to church, they kind of want to believe in religion, or they go to socialism and think the state is going to look after us.

So he does think since we’ve relied on religion for so many centuries that it can’t just be an instant, “Oh, we don’t believe anymore,” and that’s okay. But he does think for people like him and other stronger spirits, as he would call it, that this is a liberating movement. Realizing that there isn’t a God who’s got his eyes on you all the time and is telling you what to do and you’re just here to do God’s will makes you a free agent. We have to say more about freedom in Nietzsche—this is a kind of liberation. You are free to go and live your life on your own terms, but he does think that’s only a realistic option for a small percentage of the population.

Beck: We go into World War I and it’s a mess. Then we get the Dadaists, and we have kind of this toxic stew. I think the Dadaists are making fun of the elites saying, “I can do anything.” Nothing has any meaning at all any more. Is this part of the postmodernism and the modern in conflict? Do you see what I’m saying?

Hicks: Yes.

Beck: Life has no meaning, and it kind of just kind of works its way into all of the nastiness that comes in the next ten years.

Hicks: Well, I think it’s fair to say that you can see the seeds occurring culturally among then high culture before World War I, although World War I certainly is extremely important. So Nietzsche is doing his writing in the 1880s, and he’s becoming a thing before his death in 1900. That whole end of the century transition, particularly in high culture, you can see a lot of proto-Dadaist nihilism, despair, and so forth. Just at a purely intellectual, cultural level, if you are a well-educated person and you’re a sensitive person the way an artist is, you’re channeling the zeitgeist or the spirit of the times, and you’re hearing things like, “Nature, red in tooth and claw,” and we’re all just animals, and it’s instinct, sex, and aggression.

You’ve got scientists developing theories like entropy: we’re going to have, ultimately, the heat death of the universe. If you are channeling all of that, you’re looking into the abyss, to use Nietzsche’s language here. One reaction of that, of course, is just to become profoundly depressed, but I think another is to go in a humorous direction. Life is ultimately just absurd, and one can play around with the humor of that absurdity. Dada is coming out of that. It is an embracing the absurd in a somewhat whimsical, but nonetheless, serious way. It’s coming from a deeply pessimistic place, but nonetheless, you’ve got some creative energy and you’re not just going to go totally into nihilism. Then you add to all of those intellectual currents and World War I, and I think that must have been psychologically devastating.

Beck: It was.

Hicks: All of the allegedly civilized nations of the world just engaged in total brutality for four years.

Beck: And the way I read it, the churches pretty much said, “No, God’s on our side,” on both sides. It kind of was that final collapse of the lower-class faith in God, and they had nothing. They started turning to occultism, looking for any heritage to hold on to.

Hicks: Well, if you’re one of the millions of troops and you’re just an ordinary, working person or whatever and you’ve got standard religion, of course the problem of evil or the theodicy problem is going to be real for you. God is on my side. I’m doing this to other men, and they’re doing this to me.

Beck: It doesn’t make sense.

Hicks: This is not part of God’s plan. It can’t possibly be. How can there even be a God if this is the world that he’s put us in?

Beck: We have the same kinds of things happening with us now to where society is collapsing. We’ve had shocks to the system—not like World War I—but we don’t really know what we’re doing. The Great American Empire is seemingly coming undone. Nobody has an answer. There’s nonsense from postmodernism. There’s a hundred different genders. And it’s just all framed the way it was in 1920s Europe. Am I reading too much into that?

Hicks: Well, that’s a big picture assessment. I think things are actually better. I’m less pessimistic. We do have a lot of things to worry about, absolutely, and we can’t go too far down that road. In one sense, I’m not worried because I do think in American culture, Canadian culture, and broadly Western culture, which is now becoming global culture, we have huge cultural reserves that are very good. I think the vast majority of people are basically decent, basically rational, and so on, but we do have a problem with the fringes. I don’t have good demographics on whether that’s 3% or 7% or whatever.

Beck: Latest study shows 8%, which is really insignificant.

Hicks: It’s insignificant in a quantitative demographic sense, but then, qualitatively, where are those 8%? And if they are in important cultural institutions like universities where all of the future professionals and teachers and journalists and politicians are going to be educated, then that 8% matters a whole a lot more. So there’s got to be a qualitative measure as well.

But at the same time, I think about what people were struggling with in the first half of the century. You mentioned World War I, the Depression, World War II, and the Holocaust. I don’t think we are dealing with cultural and political enemies on that scale. We are dealing with postmodernists, yes. They are mostly intellectuals. We are dealing with Islamists, who are a politicalized version of Islam. We are dealing with political tensions in Russia, in China, and so on, but I don’t think those are on the scale of World War I or World War II. In that sense our enemies are much smaller.

Beck: I agree with you, so let me just say this. A part of my job is to see a little bit over the horizon and to map it, and as soon as the star-field roll starts rolling the other way, great. As long as the star-field is rolling that way, it’s okay. What do we do now to prepare in case those things happen? You have global economic collapse, and there’s a pretty good chance that could happen in the next five to ten years.

Hicks: So we want to identify all of the possible apocalypses in these sectors and have a contingency plan?

Beck: Yes, reasonable ones. What we have to do right now is start to come back together, after the 1920s and all those things happened, then you had the Great Depression. Morals meant nothing in the 1920s. I’m talking about Germany. People started to get rich, and morals kind of go out the window. Then somebody comes and says, “I’m going to reset it.” And people were ready, at least 30% were ready to have that, and the rest just kind of went along. It was too late. We are having political enemies. We are starting to enter a time that could begin to resemble 1968 America. We have to learn how to have dialogue with the people we’ve been trained to hate.

Hicks: Yes.

Beck: Or we’re going to go down that road that has happened before. So I want to talk to you about postmodernism in that framework, because most people get up and they hear, “Oh, I have to now accept this gender too.” Or, “I now have to say this, and yesterday that was okay, but today I could lose my job for saying that.” They don’t know where that’s coming from. Nobody’s recognizing it. You just comply.

Hicks: Well, the problem is the compliance element. I have no problem with us having a vigorous national discussion about how many genders there should be.

Beck: Correct.

Hicks: The biology and psychology are complicated, so we should have that discussion. We might, then, say that there are some cultural sectors that are very loud and are forcing these discussions on us. It’s all very bewildering, but that actually is fine as long as we can discuss it. And that’s the issue. The problem is the politicization of the discussion.

Beck: Right. Look, I don’t know what the reality is, but I don’t anybody that looked at Bruce Jenner and said anything but, “Oh, my gosh, you felt that way your whole life? Why didn’t you say something? We don’t want you to feel that way.” Nobody was like, “Oh, you’re a freak.” I think we’re beyond that for the most part.

Hicks: Well, again, we’ve got the 3% or whatever.

Beck: Right, so I don’t think we have that problem. The problem is that half of the country is being told, “You’re stupid. You’re racist. You’re a bigot.” And then that half now is starting to say to the other side, “You’re totalitarian, and you are going to gas us all.” Neither of those is true, but we’re not talking. So how do we do it?

Hicks: This is where, I think, postmodernism is dangerous. Because we all, as human beings, have these frustrations when we are arguing about various things. We don’t necessarily like our views being challenged, and we always have to go the extra effort to open ourselves up to that.

Beck: We’re good at challenging others but not challenging ourselves.

Hicks: And in many cases, we’re not good at challenging constructively, so we need to learn how to do this. All of these are emotional skills; all of these are cognitive skills. And I think it’s part of the human condition that good thinking and civil discourse takes a lot of work, and there are always temptations to engage in shortcuts. Even if we are a people who have thought about various things, and we know we’re decent people and we’ve thought things through, it’s hard for us to want to open ourselves up to having to rethink things. At a certain point, it’s easy for us to close the door.

I think that’s a part of human condition, but good parenting and good education do give people the intellectual, the emotional, and the social resources to be able to do that throughout their lives. The real danger is that we now have an elite in universities who are not teaching those skills. They have come to believe—this is the postmodern position—that rational discussion is not where it’s at. Emotional tolerance and a willingness to engage in civil discussion is not where it’s at. And when the teachers of the teachers stop teaching those skills and start to model different things, then you’re on a slippery slope.

Beck: How can honest teachers, who think they’re doing the right thing, say, “No, you’re just going to listen and take it, and you’re going to repeat it, and if you step out of line and use some sort of rational thought …”

Hicks: Well, you used the word honest, and I think …

Beck: That’s the problem.

Hicks: Yes. I think there are two things here. We always have teachers in any generation who are not honest about being teachers in the sense of liberal education. They don’t believe that we’re supposed to train people to think for themselves, give them all of the arguments, and so forth. There’s always the temptation, once you’ve become a teacher and have a position of power, to mold young minds. You have your agenda, and you become an indoctrinator. Every generation has that, even in the most gung-ho liberal education that is possible. People who know they are doing that know that they are being dishonest. They might mouth certain liberal education platitudes, but they know that in their heart of hearts they really are just in the game to indoctrinate.

Part of what universities should be doing is policing themselves against people who are just ideologues and not giving them tenure. We don’t do that as well as we used to. But then, I think there is another sub-species here that I don’t think that are dishonest, but they have convinced themselves that rational dialogue is impossible. This is why that I think that philosophy is most important. We need to have good epistemology that shows that, in fact, we can identify facts, that there is something to scientific method, and that each of us, even if we’re not professional scientists, should know something about evidence, argument, refutation, and be able to follow a chain of thought. As long as we don’t have a significant number of philosophers teaching that, it’s not going to trickle down into the other disciplines.

What you will have is a lot of people who are semi-educated, but what they will learn is, “Well, as with deconstruction, you can always make up whatever story you want. You can lie with statistics, you can lie with words, and even the distinction between truth and lie doesn’t mean anything.” Once that becomes the widespread intellectual ethos, then people will say, “Well, I’m not being dishonest if I’m just making up my own narrative because it fits my value framework and using whatever social power I have as a teacher to get my students to believe that. I’m just doing what everybody else does.”

Beck: That’s where we are.

Hicks: That’s where we are. So you mentioned deconstruction earlier. There’s an interesting point here. Jacques Derrida is most often associated with that, but I think of Stanley Fish, who was a very famous professor at Duke for many years before he came to my home state of Illinois. Interestingly, he was the highest paid public servant in the state of Illinois, making more money than the governor for a while. He was a superstar professor who was recruited. One of the quotations I like from him—I don’t agree with it—but on deconstruction he said, “There is no truth, there is no objectivity, and there’s no such thing as a right interpretation of text.” He said, “This is very freeing. I don’t have to worry about what the right interpretation of a text is.”

Beck: Great.

Hicks: “All I need to do is just be interesting, just be playful, and then if I’m interested in some strange reinterpretation of a given painting or a given Shakespearean text, as long as someone reads that and says, ‘Oh, that’s kind of fun, or a new way of looking at it’, that’s fine, because no one can say I’m wrong.” But once there is no such thing as a right way to interpret things, then what are professors supposed to be doing when they’re doing with their students, if we’re not training their minds, if we’re not training them to look at both or all sides of an argument? You have power, and if you’re a politicized person at all, you will use your power for indoctrination purposes.

So, the connection I make here is Frank Lentricchia, who is one of Stanley Fish’s colleagues at Duke, and he’s speaking for a whole generation. This is from a book published by University of Chicago Press, and I’m paraphrasing now, “The task of a professor is to train political activists. We live in a horrible, horrible regime. Basically, capitalism and the industrial revolution—everything is awful, sexism, racism, the whole shebang. It’s taken as axiomatic from that perspective, but people are being indoctrinated by the major cultural organs that are out there. My job as a professor is, to the extent I have power over these students, to get them angry about the system as it is. We know what comes out of the anger is a sense that, ‘I need to go out and do something,’ and that would be the activism.” So the lineage from Derrida to Fish and Lentricchia is well worn out; Derrida in the 1960s, Fish and Lentricchia writing in the 1980s and 90s, and those very bright individuals have influenced a generation, and now we have a more significant demographic who are exactly doing that.

Beck: So how do we get it back? How do we not embrace our anger and punch back?

Hicks: Well, I think we should be angry, because I think this is a betrayal. I think the anger is there, but we must go back to the Greeks and anger management. The stakes are high, and any time we have a major injustice and anger, we should be worked up about it.

Beck: I find it very difficult to talk to people, because when I say we cannot strike out, they interpret that as, “You don’t have a reason to be angry.“ This is righteous anger. This is my culture, and I feel that my country, the Enlightenment, and facts have been stolen, and they have trained a new little army to enforce it. So, you’re damn right we’re pissed.

Hicks: That’s right.

Beck: But now we have to be smart on how we fight it.

Hicks: Exactly. Your anger has to work with your reason. Your passions have to work right with your mind. So we should be activists ourselves in the cause of truth and justice, and in the American way in the American context. Those values are legitimate values, and they should be fought for vigorously. But right now the battle is not World War I or World War II. It’s an intellectual battle. And this is not just I, as a professor, saying I’m a hammer and everything is a nail. This is the most important battle. It is an intellectual battle, and it has to be fought in the universities.

Beck: Who’s fighting it?

Hicks: Well, I’m a little optimistic at this point, because my sense is that most people who were first-rate in the academic world in the 1980s, the 90s, and the first decades of the 2000s, were off doing good work. Whatever it was that they were doing, they were aware of postmodernism in various manifestations and they were just saying, “That’s just a bunch of fringe people, and I don’t need to take them very seriously. Who can possibly take that seriously? It doesn’t make any sense to me anyway.” That did leave a vacuum, and part of postmodern strategy or sub-strategies is the long march through the institutions to capture those institutions. They were playing the political game. They are capturing those institutions, but once they are in enough of a position to become a more serious nuisance, then I think the first-rate people start to pay attention. And so for the last fifteen years or so, there have been an increasing number of people in all the major disciplines—in psychology, in history, in law, in my home field of philosophy—who are taking postmodernism seriously. So, the intellectual debate is being joined, and that’s a good sign.

Beck: Yes.

Hicks: And I think also a very good sign is that postmodernism is, in part, an activist strategy, and so now that it’s done well in higher education, it’s stepping out into all other cultural spheres. And so the more general public, who’s also out there doing good work, are starting to become aware of it, and we’re also starting to see engagement on other cultural fronts as well. I don’t think there are any shortcuts. It’s going to be unpleasant, and it is going to be nasty. I think as you are suggesting, in one sense, we have at least one hand tied behind our back because we’re not willing to initiate certain tactics that they are willing to initiate. We’re going to take the high road, and I think we should take the high road. Use physical force only as a last resort and in self-defense.

Beck: Right. If it is about creating chaos and dismantling and not using reason, by allowing yourself to be angry and reacting and creating more chaos, aren’t you just hastening what they’re trying to do?

Hicks: Absolutely. And this may be a cheap shot, but I do think the postmodernists and a lot of the activists recognize that if they have to come up with evidence, they’re not going to win that game. If it’s a matter of being logical, rational, and scientific, they’re not going to win that game, so they are using the tactics that they have, and that is street fighting. Just as in other branches of the military, if you can’t compete on traditional tactics or high-tech or whatever, you use guerrilla tactics. So I think what we have is an intellectual guerrilla strategy that is being mounted here, and we do need to be willing to use force in self-defense and to keep that contained. There’s a legitimate role for security forces and police forces.

Beck: Martin Luther King asked for a permit to carry a gun.

Hicks: Absolutely.

Beck: He was denied, but he asked for it.

Hicks: That’s right. But at the same time, we have to make sure that we are reacting only legitimately in a self-defense fashion.

Beck: Yeah.

Hicks: And at the same time, we should be paying more attention to the cultural institutions. We need to reinvigorate the issues of civility, what really liberal arts education is about, what proper rationality and respect for human dignity and human rights requires, and all of the arguments and understandings that go into having a decent rational philosophy that can support a democratic republican polity. To a large extent, the postmodernists are operating in a cultural vacuum. We have taken a lot of things for granted and not defended them very well for several generations now, so we need to up our game.

Beck: Would you come back and help us with that?

Hicks: I will be happy to.

Beck: Help to teach some of the arguments that I don’t think people have thought that deeply about, at least for a long time.

Hicks: Yeah. I’m now old enough to have been on several hiring committees, and I’m at a smaller liberal arts institution and so I interact with faculty. I hope I don’t just sound like an old person at this point, but an increasing number of people who come out with Ph.D.s have not really gotten a full education.

Beck: Oh?

Hicks: And it’s not just that in the first generation or so. Obviously we can’t all read everything, but most of us have made an effort to read all of the greats and to know something about them. I noticed this about fifteen years or so ago, people would just say, “No, I haven’t read that and there’s no need for me to read that,” and it’s one of the giants in the literature, and sometimes it’s just a matter of, “Well, I’m only interested in this,” but also that’s from an alien tradition and no point reading that.

Beck: Stephen has written a book called Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault. It is well worth your time reading, and I hope to have you back.

Hicks: Thanks for the plug, and thanks for the invitation.

Beck: Thank you, sir.

Hicks: A real pleasure.

Video of this conversation is available at YouTube.

Well, I really am an old guy and one who just tonight became aware of your website ( via the Beethoven – Goethe reference).

The transcript of your interview with Glen Beck was very helpful to me in thinking about some of my reading in recent times, much of which in philosophy, where I have a very little background. But the content of your responses and the courteous and tactful tenor of your replies to Mr. Beck’s questions and comments led me to think of some of what I have been reading on the internet of the writings by Leo Strauss

If you are not too busy, would you please comment on (what seems to me) Strauss’s relevance to the themes of your interview and possibly recommend other material available on the internet for reading,

Thank you

Thank you, Michael. I have not written on Strauss, though I find him provocative.